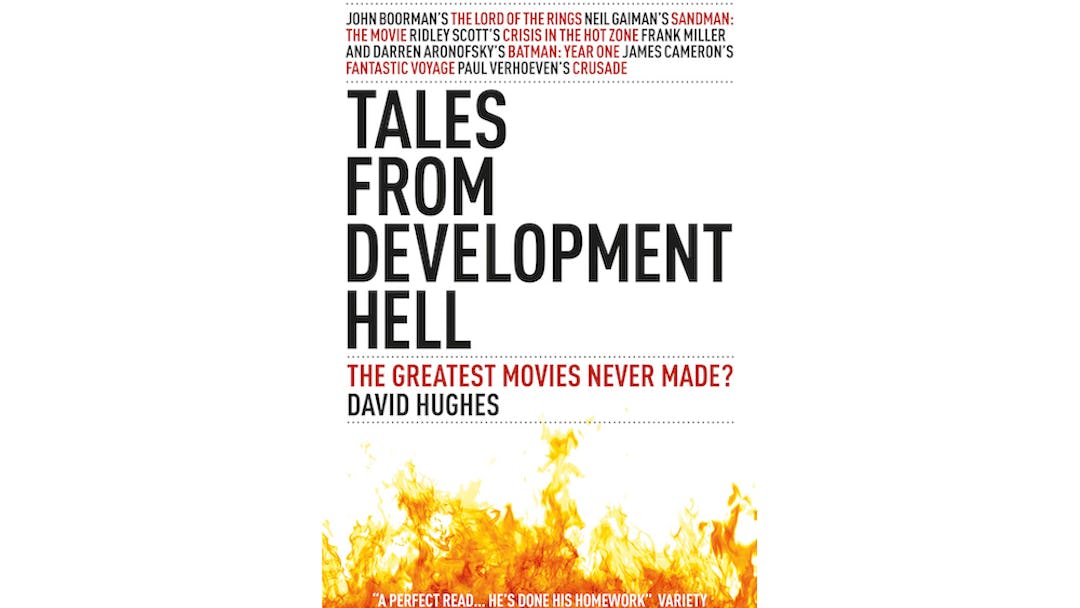

One of the dedicated cinephile’s favorite hobbies is contemplating the movies that might have been, and it’s a pastime we’ve engaged in here at Flavorwire on occasion. Because the Hollywood development process is such a fickle beast, prone to prevailing box office winds, rising and falling trends, and the particular peccadilloes of people in power, the pages of movie history are littered with the corpses of promising films that simply fell apart, for a variety of reasons. David Hughes is one of our most esteemed writers of cinematic obituaries—his books The Greatest Sci-Fi Movies Never Made and Tales From Development Hell (out today in a newly revised edition) are entertaining and detailed deconstructions of what went wrong with the movies you’ll never get to see. After the jump, we’ve assembled a few of the most intriguing movies-that-could-have-been from Tales, along with a handful of titles contributed to Flavorwire by the author himself.

Darren Aronofsky and Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One

After the critical failure of Joel Schumacher’s Batman and Robin in 1997, Warner Brothers spent seven years trying to figure out what the hell to do with the Caped Crusader. Various ideas were developed: a reboot called Batman Beyond from writer/director Boaz Yakin (Remember the Titans); the fabled Batman vs. Superman, directed by Wolfgang Peterson (Das Boot) from a script by Seven scribe Andrew Kevin Walker (yay!) and Batman and Robin writer Akiva Goldsman (wha?); and an origin story called Batman: Year Zero, from graphic novelist Grant Morrison (Arkham Asylum). But the most intriguing of the bunch was the proposed film version of Frank Miller’s game-changing graphic novel Batman: Year One, adapted by Miller and director Darren Aronofsky, fresh off his breakthrough film Pi.

“The Batman franchise has just gone more and more back towards the TV show, so it became tongue-in-cheek, a grand farce, camp,” Aronofsky told Developmement Hell author David Hughes. “I pitched the complete opposite, which was totally bring-it-back-to-the-streets raw, trying to set it in a kind of real reality — no stages, no sets, shooting it all in inner cities across America, creating a very real feeling. My pitch was Death Wish or The French Connection meets Batman. In Year One, Gordon was kind of like Serpico, and Batman was kind of like Travis Bickle.”

Miller and Aronfsky’s completed screenplay never came to pass; the director presumes the studio got cold feet about its even-darker-than-Batman-Returns tone.

Robert Rodriguez’s The Jetsons

Mr. Hughes writes to Flavorwire: “Steven Spielberg’s The Flintstones made a ton of money, so it’s no surprise that a big-screen outing for their futuristic counterparts has been mooted for the best part of 20 years. This update of the 1960s (and 1980s) Hanna-Barbera cartoon, which turns 50 this year, came close to being made by Robert Rodriguez from a script by Adam Goldberg (Aliens in the Attic), but the money fell through. Now that Kanye West is reportedly involved (no, really) the film may happen at some point – appropriately enough – in the future.”

John Boorman’s The Lord of the Rings

Numerous actors and filmmakers tried to get a film adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic trilogy made before Peter Jackson finally succeeded in 2001. One of the stranger ideas was the idea of Lord of the Rings as a movie vehicle for… the Beatles. John Lennon instigated the idea, reportedly imagining himself as Gollum, Paul as Frodo, George as Gandolf, and Ringo as Sam. United Artists, who had the group under contract, acquired the film rights in fall of 1969 for a quarter of a million dollars. Heinz Edelmann, designer and art director of their previous animated film, Yellow Submarine, was originally involved, but UA ultimately decided to go live action, and engaged director John Boorman (then fresh off Point Blank) to direct the film. The director worked with writer Rospo Pallenberg to mold the three giant books into a single screenplay, but by the time they had done so, UA had lost interest in the film — not just because the Beatles had since broken up, but because, per Hughes, “the studio decided it was too risky, too costly, or simply not commercially viable.” LOTR went on the back burner; Boorman and Pallenberg would use much of their research and location work a decade later, when they collaborated on the King Arthur film Excalibur.

Rupert Wainwright’s The Outer Limits

The author tells us: “It’s a question we’ve all asked ourselves at one time or another: what if shape-shifting aliens invaded Earth after infiltrating the world’s currency with mind-controlling nanobots? Such was the plot of MGM’s proposed sci-fi blockbuster, titled after Twilight Zone-esque mystery series of the 1960s (and 1990s). Rupert Wainwright (Stigmata, The Fog) was attached to direct one of the countless drafts, but the film withered on the vine as MGM faced the outer limits of its fund-raising capabilities.”

Ridley Scott’s Crisis in the Hot Zone

Richard Preston’s riveting 1992 New Yorker article “Crisis in the Hot Zone” was immediately pegged as prime material for a movie adaptation — so much so, in fact, that two film versions (one official, one not so much) ended up racing each other into production. The unofficial, highly dramatized take, Outbreak, made it to theaters; the authorized version, which was to star Robert Redford and Jodie Foster under the direction of Ridley Scott, sputtered out at the eleventh hour. According to Hughes, it may very well have been a classic case of too many cooks in the kitchen; though writer James V. Hart (Bram Stoker’s Dracula) cultivated a close working relationship with Preston and immersed himself in the journalist’s research, Scott and Redford brought in their own writers, each draft leaving everyone less satisfied and feeling less prepared for the looming production. Foster, unhappy with the changes the story was taking, eventually dropped out; when Redford followed suit two weeks before photography was set to begin, Fox pulled the plug on the picture. Outbreak opened in spring of 1995, benefiting greatly from consumer confusion with Preston’s subsequent expanded book of the story, The Hot Zone.

Ridley Scott’s ISOBAR

Scott (above) was also involved in another intriguing project — at its early stages, anyway. Jim Uhls, who would later pen the film adaptation of Fight Club, wrote a spec script in 1987 for a sci-fi thriller originally titled Dead Reckoning, described (in true Hollywood fashion) as “Alien on a train.” The idea of bringing in that film’s director to helm this tale of a genetically altered humanoid loose on a super-subway was certainly tantalizing; while Scott never officially signed to do the film, he was involved in its development in the time before making Thelma and Louise, even bringing in the original Alien’s designer, the Swiss artist H.R. Giger. Giger worked up various set and design elements for the film, only to find that Scott had moved on (Giger would later repurpose his train designs for Species).

Over the ensuing years, the script would go through multiple mutations, with changing titles and varying stars (including Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone) and directors (particularly Roland Emmerich) interested or attached. But that initial, Scott-helmed version is the one that sounded most promising. In Hughes’ chapter on ISOBAR, screenwriter Steven de Souza (who wrote a later, ensemble-minded draft of the script) sums up one of the book’s primary lessons: “Movies get made not because the script is great, but because somebody likes the script at that point.”

With Wings As Eagles, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger

Mr. Hughes writes: “Austrian-born Arnie had the perfect accent to play the hero of this World War II thriller, freely adapted from James J. Cullen’s novel Osterman’s War by Braveheart scribe Randall Wallace. Inglourious Basterds meets Valkyrie as disillusioned Nazi Colonel Klaus von Ostermann [sic] leads a Dirty Dozen-style army of ex-POWs to the Allied lines.”

Adam Rifkin’s Planet of the Apes

Several filmmakers (including Oliver Stone, Chris Columbus, James Cameron, and the Hughes brothers) toyed with the idea of rebooting the Planet of the Apes franchise before Tim Burton’s ill-fated 2001 “reimaginging” of the classic sci-fi film, but the most compelling may well have been the first one. Young writer/director Adam Rifkin had impressed Fox brass with his indie debut film, Never on Tuesday, so he pitched them on the idea of a new Apes film back in the early ’90s. Rifkin’s idea? “Spartacus with apes,” he tells Hughes — a story set 300 years after the first Apes, as “the ape empire had reached its Roman era. A descendant of Heston would eventually lead a human slave revolt against the oppressive Roman-esque apes. A real sword and sandal spectacular, monkey style.” Could have been silly, sure — or it could have been, as Rifkin would later muse, Gladiator with apes. Either way, it would have certainly been better than what Burton came up with.

Roger Avary and Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman

Neil Gaiman’s seventy-five issue DC comics series brought one of the label’s forgotten characters back to memorable life, winning multiple awards and establishing Gaiman as one of the most innovative writers in the game. Its aborted path to the silver screen began promisingly, with a script by writers Ted Elliott and Terry Russo that caught the attention of Oscar-winning Pulp Fiction co-writer Roger Avary, who was interested in directing a film adaptation for Warner Brothers. The trio worked closely to create a new draft, which was widely praised by fans of the books. But Avary left the project in January 1997, due to “creative differences” with producer Jon Peters, who Avary wrote “wanted a Sandman in tights and a cape punching out The Corinthian.” (This wouldn’t be the first time Peters didn’t quite “get” a superhero he was adapting for film.) The script went through multiple additional drafts (each reportedly worse than the last), but still languishes in Development Hell; according to Gaiman, “with any luck it will remain there forever. I would much rather that a Sandman movie were never made, than that a bad Sandman movie was.”

Christopher Nolan’s (or Brian DePalma’s) Howard Hughes Project

The life of Howard Hughes — bedding starlets, flying airplanes, producing movies, growing fingernails — was so dramatic that it’s somewhat surprising that it took Hollywood until 2004 to mount a full-fledged biopic (not counting Jonathan Demme’s Melvin and Howard, where the mogul was a secondary character). But on the way to The Aviator, everyone from Warren Beatty to Michael Mann to the Hughes Brothers to William Friedkin to Milos Forman were attached to multiple would-be Hughes movies. Brian DePalma came very close to directing Nicolas Cage in a widely-praised screenplay from David Koepp called Mr. Hughes, but that one got thrown on the back-burner when the trio’s 1998 collaboration, Snake Eyes, tanked. (Considering the quality of that movie, maybe this was a film better left undone.) It ultimately came down to a race between The Aviator (which originally had Mann at the wheel) and an adaptation of Richard Hack’s book Hughes, which was first in the hands of French Connection director Friedkin, but was then moved to up-and-comer Christopher Nolan, who had just followed Memento with Insomnia.

Nolan told reporters at the time that he was attracted to “the extreme nature” of Hughes’ story, “the glamour, the wealth, then the claustrophobic unhappiness.” Nolan cast Jim Carrey in the role, but when The Aviator beat Nolan’s Hughes project into production, he put it aside — and went on to rescue the Batman series. As time as passed and Nolan’s star has continued to rise, though, rumors have persisted that he still might take a crack at the Hughes story; at least ten years would pass between The Aviator and his film, even if it is the first one he makes after The Dark Knight Rises. “Any time you go into make a film there are other factors around,” he told the Z Review in 2002, “and you just have to believe in the project you are doing, that it will find its way to get made.”