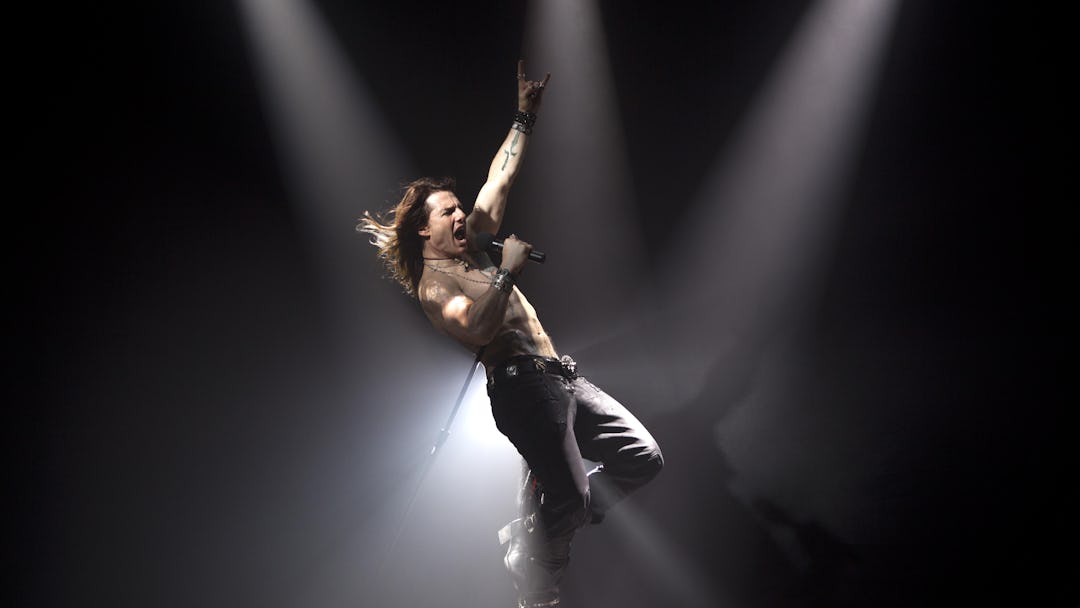

In spite of all our best efforts, Rock of Ages — currently sitting at 38% fresh among top critics on Rotten Tomatoes — is out this Friday, because if the multiplexes were missing anything this summer, it’s painfully earnest renditions of “Waiting for a Girl Like You” and Tom Cruise in assless chaps. Yes, the movie musical has fallen on rather hard times, but if we can learn anything from tracking its ebbs and flows of popularity, it’s that you can never count the genre out. So we’ve put together a brief but educational timeline to illustrate the many beat-downs and comebacks of the movie musical.

1927: The Jazz Singer

The very first feature-length (partially) talking film was also, wouldn’t you know, the very first movie musical. Al Jolson sang four songs in the film, and audiences ate it up; the first “all-talking picture” (as it was promoted), the following year’s Lights of New York, had three production numbers as well. In the first flush of talkie-fever, musicals were all the rage — why bother making a talking picture if they weren’t going to sing and dance too? — and when the first few were box office hits, the studios went nuts. The put out over 100 musicals in the single year of 1930, and created a glut that immediately soured the form for audiences who were, in the early days of the Depression, suddenly not that interested in gaiety onscreen. In 1931, that number dropped to only 14 musicals, with studios scrambling to take musical numbers out of films that had already been completed. The musical, it seemed, was dead.

1933: Busby Berkeley and Astaire/Rogers

But it wasn’t. Part of the problem with early musicals was the nailed-down clunkiness required by the bulky early sound cameras, but choreographer Busby Berkeley realized that if song and dance numbers could be performed to pre-recorded sound that was played back on set, microphones — and thus the stationary cameras — would be unnecessary. The numbers he put together for Lloyd Bacon’s 1933 hit 42nd Street had a sense of vitality and life that was refreshing; the camera moved with grace, and the angles were stunningly inventive. He choreographed three more hits in ’33 (Gold Diggers of 1933, Footlight Parade, Roman Scandals, and Fashions of 1934) before Warner Brothers promoted him to director, where he made several more enjoyable musical features. His fluid camera work and sophisticated style led to a rejuvenation of the form’s popularity — as did RKO’s decision to pair supporting players Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers up for the 1933 musical Flying Down to Rio, which was the first of their ten beloved onscreen collaborations.

1940s: The Freed Unit

By the mid-’40s, musicals had worn out their welcome once again, so MGM put Arthur Freed (who had made his name as a songwriter and producer of Mickey Rooney/Judy Garland movies) in charge of their musical production unit. Freed’s lush, Technicolor musical extravaganzas became Hollywood’s gold standard, while the producer established a reputation for allowing his directors and performers a creative freedom all but unheard of within the confines of the studio system. As a result, they crafted some of the finest musicals ever made, including Meet Me in St. Louis, Till the Clouds Roll By, Easter Parade, On the Town, The Band Wagon, An American in Paris, Gigi, and Singin’ in the Rain (which was based on a song that Freed wrote with Nacio Herb Brown).

The hits of the Sixties

Box office receipts nosedived in the 1950s, and not just for musicals; as television grew, movies took a giant hit in attendance, and studios tried to compensate by turning their product into giant “events” that would overpower the small screen with sheer showmanship. (Sound familiar?) In the 1960s, big Hollywood musicals — almost invariably based on Broadway hits — would run well over two hours in glorious widescreen, often with premium-priced “roadshow” engagements before their general release. The ploy worked, at first, and movies like West Side Story and The Music Man were among the biggest successes of the decade. The stage smash My Fair Lady was a no-brainer for the screen, but producers decided to replace Julie Andrews, who’d never been in a film, with known quantity Audrey Hepburn (though Hepburn’s singing voice had to be dubbed by Marni Nixon). Andrews had the last laugh, though: Disney cast her in Mary Poppins, for which she won Best Actress in 1965 — the same year that My Fair Lady won Best Picture, though Hepburn was not even nominated against Andrews. The actress went on to star in The Sound of Music, which became not only the year’s highest-grossing film, but displaced Gone with the Wind as the biggest box office hit of all time (without inflation, anyway). Once that happened, the studios eagerly cranked up their production of big-budget, big-name, big-screen musicals…

The flops that followed

…which very nearly put them out of business. The success of the Elvis Presley and Beatles vehicles in the previous decades were hints that maybe audiences weren’t just looking for squeaky-clean road-show musicals; by the time the Sound of Music imitators started hitting in 1967, the hot movies of that and the previous year were Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, The Graduate, and Bonnie and Clyde — tough, candid, realistic films that took advantage of the new permissiveness in content and targeted a young audience that wasn’t interested in movies where people burst into song. The bloated box-office duds piled up like wrecked automobiles: the stage adaptations Camelot, Sweet Charity, Paint Your Wagon, and Man of La Mancha; the Julie Andrews vehicles Star! and Darling Lili; Barbara Streisand in Hello Dolly and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever; and My Fair Lady star Rex Harrison’s Doctor Doolittle. Audiences passed them all by for the likes of Easy Rider, Midnight Cowboy, MASH, and The French Connection.

The 1970s

Not every big musical tanked — 1971’s film version of Fiddler on the Roof was a solid hit, for example. But by 1972, the few musicals that were landing, like Cabaret and Lady Sings the Blues, dealt with darker subject matter. Attempts were made throughout the decade to revitalize the form, but most efforts (including Barbara Streisand’s Funny Lady, the film version of A Little Night Music, Scorsese’s New York, New York, and Peter Bogdanovich’s notorious At Long Last Love) flopped; even The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which would become one of the decade’s most iconic musicals, failed at the box office upon its initial release. 1977’s Saturday Night Fever wasn’t a musical per se, as it featured “source music” rather than singing characters, but it was the closest thing to a movie musical success in half a decade, and made a bigger star of John Travolta, who starred in Grease, a genuine musical hit, the following year.

More flops

Grease’s success proved an anomaly, however; the musicals that followed it in the late ’70s and early ’80s (The Wiz, Hair, Can’t Stop the Music, The Apple) met with equal critical scorn and box-office indifference. Olivia Newton-John’s Grease follow-up Xanadu was a washout — hell, even Grease 2 bombed. Annie was one of the biggest Broadway hits of the ’80s, but Columbia lost money on its big-budget 1982 film adaptation; A Chorus Line was Broadway’s longest-running show, but its 1985 film version couldn’t earn back its budget. However, in 1986, Warner Brothers had an unexpected sleeper hit with a movie-turned-off-Broadway-musical-turned-movie called Little Shop of Horrors, directed by Frank Oz and featuring the songs of Alan Menken and Howard Ashman, two composers who would soon help bring the zombified movie musical back to life — albeit in an altogether unexpected form.

1989: The Little Mermaid

Disney’s animated features had always been famous for their memorable songs, but the tunes had become less fanciful in the 1970s and 1980s, and the studio’s recent attempts at darker fare like The Black Cauldron had tarnished their name (and box-office dominance). But some bright soul over at Disney got a look at Little Shop of Horrors, was presumably impressed by Ashman and Menken’s snappy lyrics and hummable melodies, and hired the composers to write songs for their upcoming film of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. It was the studio’s best film and biggest hit in years, kicking off what became known as “The Disney Renaissance”: a series of outstanding animated films (Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, The Hunchback of Notre Dame), with music provided by such esteemed composers as Ashman, Menken, Stephen Schwartz, and Tim Rice. And, in a nice bit of circularity, many of their songs ended up on the Great White Way, when Disney discovered a lucrative post-release revenue stream by turning them into big Broadway musicals.

2001-2002: Moulin Rouge and Chicago

Eventually, however, Disney audiences got tired of the tunes, and the rising popularity of their non-musical Pixar releases made Disney musicals less the rule than the exception. Disney tried to parlay Menken’s skill into the live-action world with 1992’s Newsies, but it laid an egg at the audience and was lanced by critics (yes, fine, it’s a cult classic now, fine). The musical wasn’t hot again for nearly a decade, until Baz Luhrmann (whose 1996 adaptation of Romeo & Juliet had the frenzy and pace of a musical, if not the style) made Moulin Rouge, his hyperactive jukebox musical that everyone seems to love but your film editor, so let’s leave it at that. Luhrmann’s stylized movie was a surprise hit, and was nominated for eight Oscars, including Best Picture. The following year, that award went to Rob Marshall’s film version of the Broadway musical Chicago; it was the first time a musical won Best Picture since 1968.

Now

Musicals are still a novelty, but occasionally one hits: Enchanted, for example, or the High School Musical series, or the offbeat Hedwig and Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog. After Chicago’s critical and box-office success, several other Broadway hits made the transition to the big screen, with hit-and-miss results. Dreamgirls, Hairspray, Sweeney Todd and Mama Mia saw healthy box office in spite of mixed reviews, though for all of the fanaticism over Rent and Phantom, their movie adaptations were decidedly unloved. Which brings us up to this week, and Rock of Ages, which truly is muddled and painful and silly enough to put the genre into the ground for a few years. But even if the critics all hate it and no one goes, one thing is certain: it won’t kill the movie musical. Clearly, it just can’t be done.