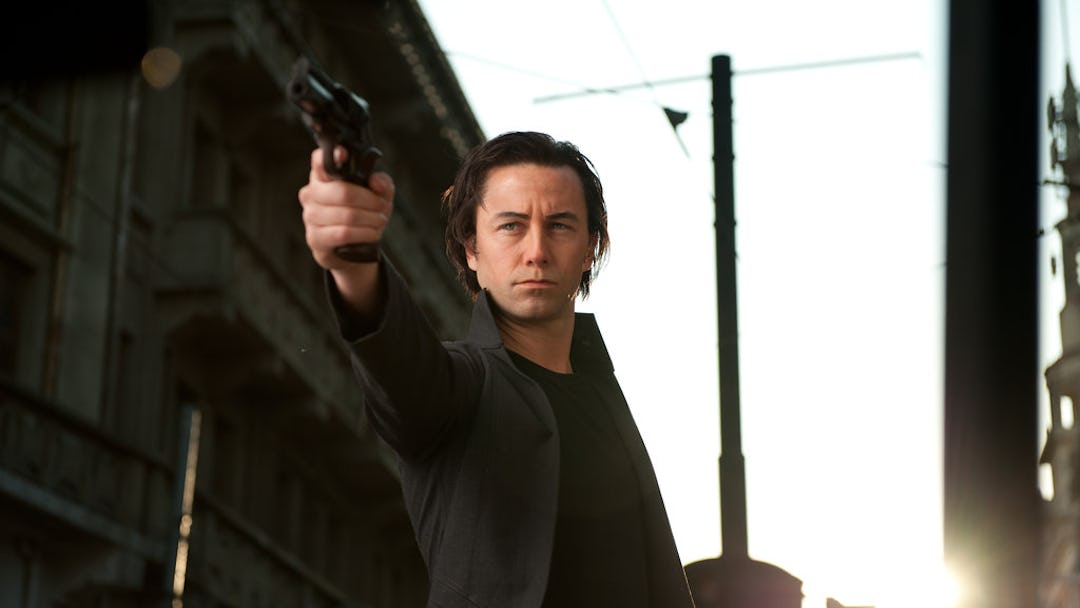

What gets your attention first about Rian Johnson’s Looper is its speed — on a basic level, it’s just a very fast movie, the text, cuts, and exposition coming at the audience hard and sharp. That pace is established in its opening scene, in which its hero (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) stands in a field, checks his watch, takes out his earbuds, and waits. The second a hooded body magically appears in front of him, he blows the poor soul away. Boom, cut, next scene.

Looper is a movie that wears its jazzy, ebullient style on its sleeve. Writer/director Johnson, who previously crafted the smashing Brick and the enchanting Brothers Bloom, is one of our giddier filmmakers — he’s intoxicated with the sheer act of movie making, and his enthusiasm is infectious. But he’s also got a magician’s gift for diversion; in retrospect, one of the most remarkable things about Looper is how it starts as one movie, and then slyly transforms itself into something else entirely.

In its enthralling first act, it plays like a hybrid of science fiction, action movie, and noir, aping less the look of the latter than its cold, dark heart (and its necessary hard-boiled narration). Gordon-Levitt plays Joe — the coincidence does not feel accidental — a hired killer with a very specific beat: he and his fellow “loopers” kill targets sent back in time from the future, where time travel has been invented but is not legal. It’s the currency of gangsters, who use it for convenient and bloodless (for them, anyway) dispatching of those who need rubbing out.

Unfortunately for the loopers, their final mark is a future version of themselves; their aged form comes with a hefty final payout and the knowledge that they’ve got 30 years until they come tumbling through the vortex. Which is all good and well until Joe’s future self shows up without the customary hood, and he finds it harder than expected to pull the trigger on himself. The escape of future Joe (Bruce Willis) puts both men on the mob’s hit list, and sets up a clever dynamic between them: Willis has to protect Gordon-Levitt out of self-preservation, but Gordon-Levitt has no motive for reciprocating. Quite the opposite, in fact.

More than that, I won’t reveal; suffice it to say that Johnson changes gears in the film’s second half, taking it in an unexpected direction and bending his story into some very interesting shapes. But that’s a testament to his filmmaking acumen — he knows the value of changing the tempo, and of a well-executed sidebar. One such sequence, a montage visualizing the thirty years between young and old Joe, appears at first to be a narrative flourish, a dark cousin of that heartbreaking sequence in Up. But it turns out Johnson is constructing a loop of his own, filling in some vital gaps in connecting these two versions of the character.

Thankfully, the Bruce Willis who can be bothered to act shows up here, and there’s something wonderful about both the weathered gravity he invests in the role, and the way Gordon-Levitt soaks it up and, in turn, makes his own work more interesting. And Emily Blunt brings a remarkable sense of calm to the slam-bang proceedings, while Johnson has the good sense to introduce her in a way that allows us to spend a couple of minutes appreciating her, and the fact that she’s in the movie now.

The relative quiet of the second act, however, is merely allowing us the courtesy of catching our breath for the climax, which quite simply left this viewer agog. But the reason that the closing sequences deliver in such a big and satisfying way has less to do with explosions and effects than it does with the realization that the filmmaker is in love with his narrative as much as he is with his windup tricks. There is a big set piece near the picture’s conclusion that includes the decidedly trash-pleasure sight of Bruce Willis running down a hallway with a machine gun in each hand, and I swear to God, it means something, and you’re emotionally invested in it. The film’s final confrontation leaves you breathless, but as much for the force of its emotion as for the skill and precision of the craftsmanship. Maybe I’m overselling it; maybe I was simply overcome by the increasingly rare sight of a studio blockbuster made with wit and intelligence. Or maybe, with Looper, Rian Johnson has made a popcorn movie into a work of art.