It’s always a strange thing to get upset about the death of someone you don’t know personally, but I remember exactly how I felt when I heard that Joe Strummer had died of a heart attack at just 50, a decade ago today. It wasn’t a melodramatic, teeth-gnashing kind of feeling — it was more like a quiet hollowness, a sadness that a person who’d been an indirect but significant influence on my life was no longer on this earth. As we get older we tend to forget how profoundly art — and, especially, music — affects us when we’re young. So if you’ll permit a bit of personal reminiscence here, dear readers, here’s why Joe Strummer and the Clash really were the only band that mattered to me for a while in my life, and are part of the reason why I’m sitting here writing this for Flavorwire, 10 years after Strummer passed away.

Punk’s DIY spirit has been much romanticized over the years, and as an avid teen, I consumed every book I could find on the subject — first UK-centric books like Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming, then tracing the movement’s roots back across the Atlantic via books like Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me. The history of punk taught me how completely by accident “scenes” begin, how their key players and their narratives are defined in retrospect — and how, like art itself, their destiny and direction take on a life of their own once they’re put out into the world, lurching in unexpected directions and almost inevitably ending up something very different to what they began their life as.

So it went with punk, of course, as anyone who’s stared aghast at the existence of Green Day’s recent trilogy (or the likes of Blink-182, generally) can attest. But the central notion of punk’s narrative — the idea that you could do it yourself, that you didn’t need expensive gear and/or years of formal training to make music and express yourself to the world — has proven one with real staying power, manifesting later in everything from the roots of rave culture to the slew of bedroom electronic producers who’ve emerged in recent years, their very existence a testament to the idea of doing it yourself.

It’s also fascinating, however, just how quickly punk itself moved away from this idea. A movement whose central tenet idolized creation soon became — not entirely, in fairness, through any fault of its own — a movement identified with destruction. This idea was driven by a hostile news media, but it wasn’t entirely untrue, either — punk always pushed the idea of a sort of year zero fundamentalism that sought to banish all that had come before it, and as such it’s not surprising it soon became a place to find bands defined more by incoherent rage at everything than bands with anything interesting to say. It’s a fine line between anarchism and nihilism, and the UK scene, at least, seemed to cross this line fairly quickly (the US scene is another question entirely, of course.) Whatever the cause, it seemed that by the end of the 1970s, when the Pistols were long gone and post punk was yet to come, and the filth and the fury was all that mattered, bands bucking this trend were very much few and far between.

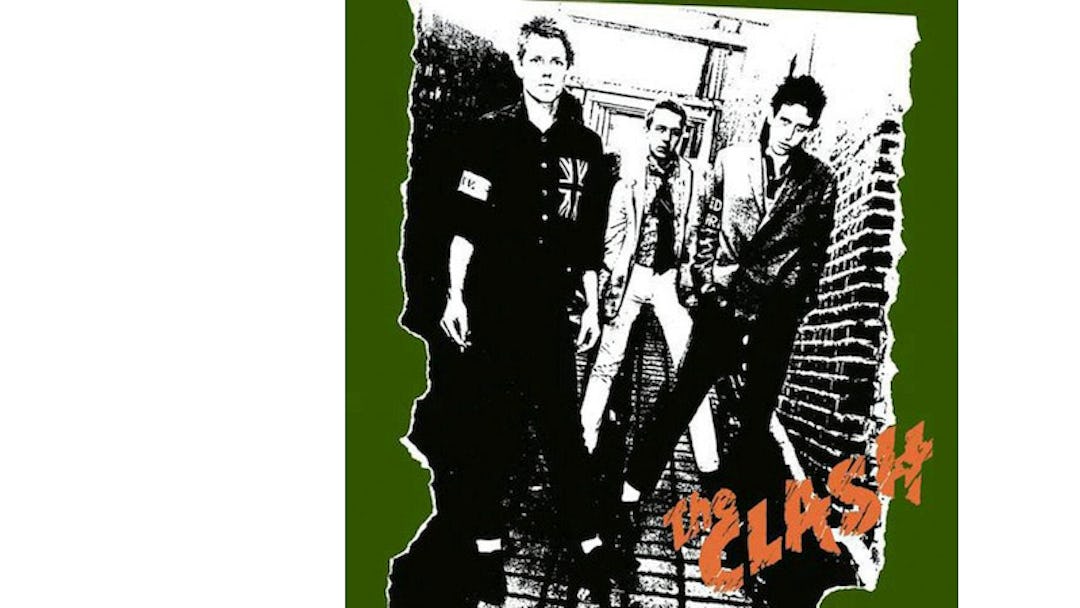

Which brings us to The Clash. They started life as Sex Pistols devotees, with Strummer having a sort of Damascene conversion after seeing the Sex Pistols support his band the 101ers, soon after breaking up that band to form The Clash. The band’s first single “White Riot” was as punk as punk gets, demanding “a riot of our own,” but even by the time their debut LP came around, they were embracing reggae and generally proving more musically visionary than their contemporaries, embracing the idea of punk as a liberating force, not a studded creative straitjacket. They were the existentialists to the Pistols’ nihilists, a band who wanted to rebuild the world rather than cavort gleefully in its ruins. And so, while punk devolved into fundamentalism, a home for a gazillion identikit bands with mohawks who mistook the “Here’s three chords, now form a band” idea for a veneration of ineptitude and ignorance, The Clash expanded their horizons.

London Calling and Sandinista!, in particular, took the idea of deconstructing music and ran with it, finding the band romping happily through the history of rock ‘n’ roll (and beyond) and assembling the music they found into a heady mixture sounds old and new. And, just as unfashionably, the band had something to say. Earnestness has long been seen as a death sentence in pop music, the polar opposite of a rock ‘n’ roll coolness that’s too cool to care about anything at all. But for a while, at least, The Clash managed to transcend this — they sang about the Spanish Civil War and capitalist alienation and Falklands-era conscription and a wealth of other topics, and did it with a degree of eloquence and intelligence that would be lost on the majority of their contemporaries.

And, yes, they did it all while signed to CBS — it seems to have become fashionable to identify their signing a major label contract as the moment that killed punk, but it always struck me as a stroke of genius. To paraphrase Leonard Cohen, where else can you change the system but from within? It’s always harder to try to do something than to do nothing, which is perhaps why the Clash were mocked by punk fundamentalists for abandoning their “No Elvis, Beatles and Rolling Stones” mantra to support the Who throughout the USA and for playing Shea Stadium (the real one, Brooklynites.) But really, what’s the use of preaching to the converted, in playing the same venues to the same fans until the end of time?

Strummer was a man with his faults, of course — he later spoke of his regret over sacking of Nicky “Topper” Headon, rather than helping the drummer with his burgeoning heroin addiction, and his comprehensive shafting of Mick Jones remains one of rock ‘n’ roll’s most unedifying moments. Once the Clash ended, imploding in the mid-’80s with their creative peak long behind them, Strummer wandered in his own personal wilderness for years. To me, this always seemed just as important as the Clash’s greatness — here was a man who was a man, not some sort of distant rock god. He tried, he fucked up, and he tried again, flirting with acting and The Pogues before forming the Mescaleros in the late ’90s and recording three excellent albums.

The third of these, Streetcore, remained unfinished at the time of Strummer’s death and was released posthumously. It remains a personal favorite, and its final track — a cover of Bobby Charles’ “Before I Grow Too Old” under the title “Silver and Gold,” is one of music’s most poignant epitaphs. “I’m gonna go out dancing every night,” sings Strummer, “I’m gonna see all the city lights/ And do everything/ Silver and gold/ But I’ve got to hurry up before I grow too old.” The music stops, and you hear him say in satisfaction to the engineer, “OK, that’s a take!” And that’s it — the last we’ll ever hear from him.

But they’re words to live by, aren’t they? And so, on the tenth anniversary of his death, I’m remembering and celebrating the life of a man I’ve admired since my teens, a man whose work proved to at least one skinny Australian teenager and wannabe writer that you could do it yourself, and that the future really was — and remains — unwritten.