The unexpected and altogether too early death of James Gandolfini has prompted an outpouring of sadness and affection on social media and the blogosphere, and it’s not hard to guess why. He played one of television’s most iconic characters. His body of film work was impressive — he was one of those actors who elevated anything he popped up in. He was, according to pretty much everyone who encountered him, a genuinely nice guy. He left an infant daughter. And so on. But there’s something else happening; the warmth and grief emanating from his fans and admirers is more personal than that. It doesn’t feel like we lost an actor we liked; it feels like we lost a guy we knew. That personal connection isn’t just what makes his death so unfortunate — it’s part of what made him such a great actor to begin with.

The key to the relatability that defined James Gandolfini was his vulnerability. The entire premise of the character of Tony Soprano — the prism through which most viewers got to know the actor — was that he wasn’t just the hard-nosed, cold-hearted crime boss familiar from gangster fiction. He was also a regular guy with real problems: a prickly relationship with his mother, a complicated dynamic with his strong-willed wife, uncertainty about how to communicate with his kids, and what kind of figure he wanted to be in their lives. The Sopranos showed us the Tony that those in his orbit saw, roaring around the house, busting his underlings’ balls, sneaking and whoring and lying and bruising. But it also allowed us to observe his private moments, alone and in the therapists’ chair, in which the burden of those acts weighed heavily upon him.

That sense of an inner life was a quality that shined through in his film work as well. Think of the otherwise forgettable The Mexican, a Brad Pitt-Julia Roberts vehicle in which Gandolfini stole the show outright, playing a thug who is quietly revealed to be gay. The actor didn’t adopt embarrassing physical or vocal traits in some ill-conceived attempt to “act gay” — in fact, he kept his guttural Sopranos voice (in interviews, his speech was cleaner and slightly higher-pitched) and basically played the character like a Tony Soprano who likes dudes.

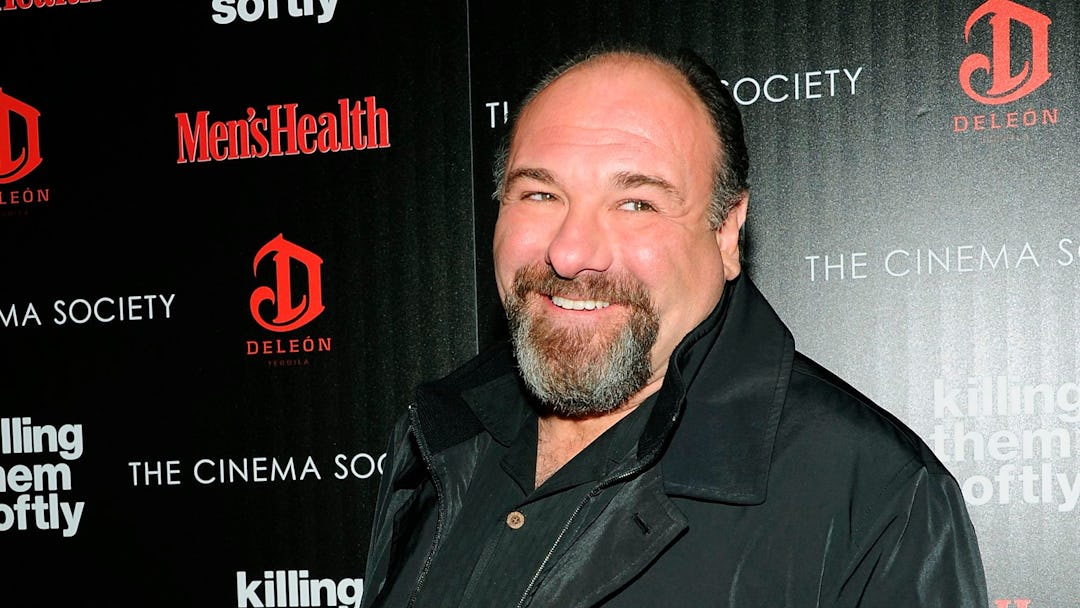

There were also shades of his most famous character in last year’s underrated Killing Them Softly, in which he appears halfway through as Mickey, a washed-out hitman who’s like a cross between Tony Soprano and Glengarry Glen Ross’s Shelly Levene. Gandolfini only has two scenes in the picture, but what a pair of scenes — one in a bar and one in a hotel room, both with Brad Pitt, both in which he seems to have decided that he’s been brought in not to do a job, but to share his sad story, to serve as a cautionary tale.

His best characters were like that — brought in to move a plot forward, but with ideas of their own. There was never a sense that they were at the service of the narrative, even when they were; you got a sense that they were living before the movie got to them, and they would continue to do so long after it was over. That is, in a sense, what all good movie acting is about, but the degree to which Gandolfini laid his characters bare — whether it was Tony Soprano’s heartbreaking panic when his ducks departed, or Romance and Cigarettes’ Nick Murder singing his guts out on his front lawn, or Carol in Where the Wild Things Are discovering mortality — made it feel like he was sharing something personal and private with the viewer. And that’s why he felt like family.

“It’s like showing emotion has become a bad thing,” Gandolfini told Vulture’s Matt Zoller Seitz. “Like there’s something wrong with you if you’re really in love or really angry and you show it. Like if you feel those powerful emotions and you express them, instead of keeping them inside or expressing yourself politely, then you must be someone who needs therapy, or Prozac. That’s the world we’re in right now.” In a wonderful and unexpected way, Gandolfini and the characters he played helped fuse that sensitivity, vulnerability, and emotional openness with our more deeply entrenched notions of machismo and masculinity, and for that — among many, many other things — we owe him a debt of gratitude. And because he shared that openness with us, his passing stings just a little more.