We don’t really trust anything anymore: government officials, banks, corporations. There might be something in the water, the milk might have growth hormones, they’re spraying stuff in the subways, and the president could be reading your email. The worst part? All of these things were discussed or foreshadowed in an episode of The X-Files.

I like to think of the show’s premier as something about as close to divine intervention as possible: exactly two decades ago I found myself at the crossroads of my adolescence, moving from the undefined double digits of a 12-year-old to become a full-fledged teenager. What’s more, according to ancient traditions that I was starting to reject, I was becoming a man. God, parents, society in general; I started to question all of these things as any good teenager does, but I needed something to center it all around, some weekly outlet for my newfound skepticism.

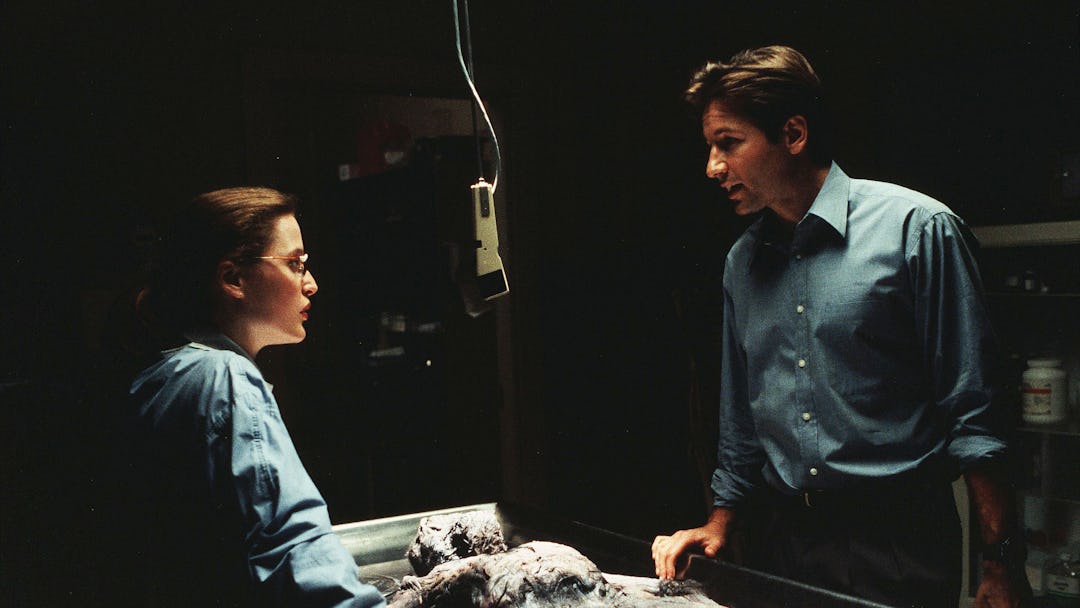

It was 20 years ago tonight — a little over two months after my 13th birthday — that FBI Special Agents Fox Mulder and Dana Scully were thrown together in the Chris Carter-created show’s pilot, and I found myself hooked on not just the show’s plot, but what I perceived to be the central theme and overarching message of the show: question everything, because “they” are lying to you. This was personally empowering for me, but I think its impact went beyond a few angry teenagers in the suburbs, because when you stop and think about how much the world has changed to make The X-Files seem even more plausible, the show seems an eerie harbinger of even darker things to come.

At its heart, The X-Files was great horror science fiction, which automatically appealed to me, as I had already been snacking on a diet of comic books and Stephen King, and even attempting to read Frank Herbert’s Dune. Every week, you got either an episode in the “Mytharc” — the part of the central storyline that dealt with the search for extraterrestrial life, and the conspiracy by some unseen powers-that-be to hide the otherworldly civilizations — or you got one of the show’s Monster of the Week episodes. Regardless, The X-Files always flashed its famous “The Truth Is Out There” slogan in the opening credits, a sure sign that no matter what, you’d be mired in some sort of conspiracy over the next hour.

The odds were stacked steeply against Mulder and Scully from the outset. There were points — like the infamous fourth-season Texas Chainsaw Massacre-meets-Deliverance episode “Home,” with its shots of dead, diseased babies and incestuous, limbless redneck mothers — at which the show invited us to look past the gruesome visuals to find an almost Don DeLillo-esque dark satire on subjects as ambitious as globalization and the America Dream. The X-Files featured famous monsters from the Golem to vampires, and an abundance of aliens that wanted to colonize the planet with help from government officials, but what it did best was what great science fiction is supposed to do: it pointed out our real-life civilization’s flaws, while also forewarning what would happen if we continued to go down a certain path. It was, at times, satirical; at other moments the show was straight to the point if you were paying attention — but more often than not, The X-Files was the most subversive thing on television.

Today hardly a week goes by without the 24-hour news cycle seizing upon some new person or organization — be it Edward Snowden, Julian Assange and WikiLeaks, the Occupy movement, members of the Tea Party, Glenn Beck — loudly decrying the various injustices committed by people in power, the rich, and the government. While members of the Tea Party and the people who camped out across the country screaming for the 99% to get their fair share might not exactly see eye to eye on, well, anything, what they have in common is that their messages have been historically dismissed as fringe claptrap by the majority of Americans who would rather just go on with their quotidian lives. I’m not saying that The X-Files bears the majority of responsibility for that shift, but a television show that (at its peak) pulled in nearly 20 million viewers per episode, and took every opportunity to drive home the point that everything we believe in and take for granted is a lie, had to play some role in bringing different and potentially extreme ways of thinking to the masses.

Of course, The X-Files came out at the perfect time, growing up right alongside the home computer. Mulder and Scully were questioning received wisdom and searching for the truth right before the eyes of already-jaded Gen Xers, as well as millennials who grew up with the creations of Steve Jobs constantly at their fingertips. That’s why it shouldn’t be surprising that The X-Files was one of the first shows to take the rogue computer of Kubrick’s HAL 9000 and give it an Internet connection in the 1993 episode “Ghost in the Machine.” It was the show that most closely coincided with the dawn of the Internet era; it helped cultivate the idea that we should mistrust the upcoming age of connectivity. As the show reached its May 2002 finale, and through the two feature films that followed the series’ end, it glorified questioning authority in a way that had particular resonance for people who came of age behind a laptop.

When the show premiered, I wasn’t old enough to totally wrap my head around some of its themes, but the fact that The X-Files was scary (but not that scary) kept me coming back until I was ready to start picking up on its subtle nods to real conspiracy theories. And when I did, it stuck. From the overarching alien storyline that is just as much about how much the government isn’t telling us as it is about spacemen to the fifth-season episode “The Pine Bluff Variant,” in which a terrorist from an anti-government militia unleashes a flesh-eating biological weapon on unsuspecting moviegoers — an episode that I think about every time I reluctantly enter a dark theater — The X-Files did as much to get viewers to ask good and necessary questions about the world around us as it did to fuel paranoia. It was aware of its predecessors, from The Twilight Zone to Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and knew cult authors like William Gibson and Tom Maddox were its bread and butter, even going so far as to invite them to write a few episodes. Dana Scully was a skeptic, Fox Mulder was a wisecracking believer, and I wanted to figure out how to be like both of them; everything was corrupt, just about everybody had a hidden motive, and whether you’re a kid in high school or somebody just punching the clock day in and day out, seeing that on network television resonates. The X-Files was — and remains — the most anti-authoritarian show ever to air on television, and the perfect outlet for people of any age who wanted to find some truth in a world full of lies.