The significance of boxing in America goes way beyond two people jabbing at each other. What we call “the sweet science” is an apt metaphor for our culture itself: two fighters are paid to beat the pulp out of each other while sponsors, promoters, and gamblers exchange bags of money over the outcome of the fight. It is evolution and industry; evolution because it is survival of the fittest, industry because there is money to be made from the violence.

Yet most striking, when you look at the history of the sport over the last 125 years, are the people sent into the ring to do battle, their backgrounds, and what that all means: Irish immigrants and their children in the 1800s and early 1900s, Jewish and Italian immigrants in the first half of the 20th century, and Latinos and African Americans since then. The plain fact is that boxing is a sport long dominated by people from backgrounds and cultures that have had to deal with the most adversity in this country. Those are the people whose bodies have been used to make other people rich — and in most cases, when their time is up, the money makers have no more use for them.

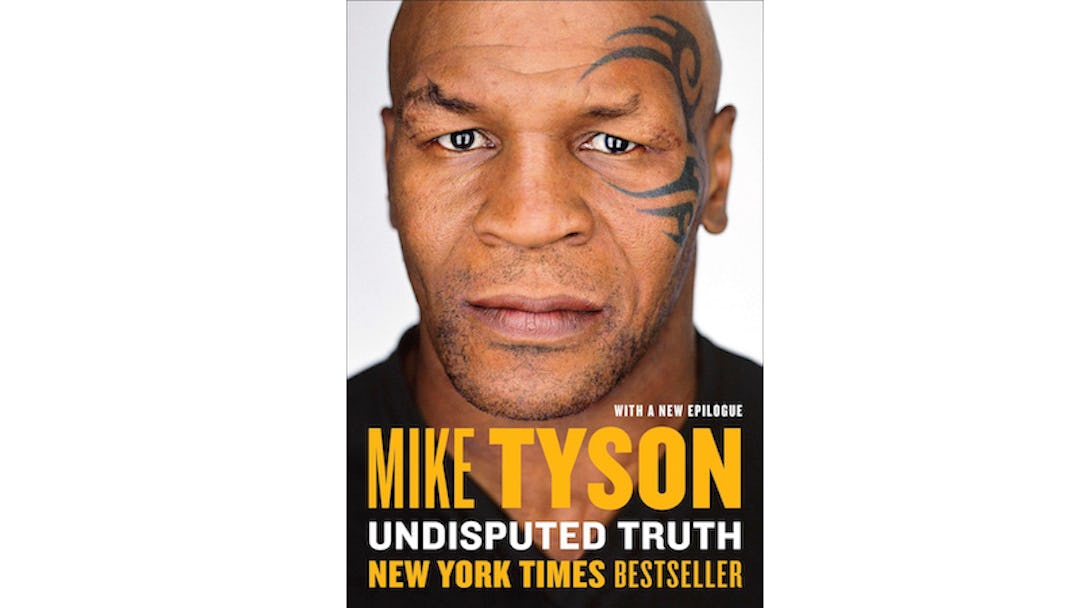

“I was just a dumb nigga being used, that’s all I’ve ever been in my life,” Mike Tyson writes in his new memoir, Undisputed Truth. The quote is powerful, and could have come from any part of the book discussing his well-documented boxing career, but instead appears in the latter part in which Tyson discusses the journey he took to Mecca and Medina after converting to Islam. This is a moment when Tyson has, we’re led to believe, found some peace in a life that has been in constant turmoil. It’s but one startling moment in a book filled with striking sentences that underline the fact that the only thing Tyson — like many boxers before and after him — had to do to survive the violence he saw every day was to become violent himself. Unlike most people in his situation, however, he made lots of money off of his brawn. His is a story of rags to riches to rags to whatever spot he’s in now, both financially and spiritually, and that’s why it’s difficult to think about or describe his book without using the word “Dickensian.”

But it’s also impossible to get past the fact that Mike Tyson was convicted of raping a woman. It haunts every page of Undisputed Truth, no matter whether you blame it on a screwed-up justice system and an unfair trial or simply believe that Tyson is just a bad person — much like he himself seems to think, evoking Dostoevsky when he confesses, “I’m filthy and I’m wretched” — who was ruined by a lot of people who could have cared less about him. He proclaims outright in the book’s prologue, “I did not rape Desiree Washington. She knows it, God knows it,” and whether or not you believe that to be true, there is no doubt that Tyson — even if he’s also an outright bad seed — is also a victim, stuck in a culture permeated by institutionalized racism and a product of a long history of oppression.

No matter how deplorable I find Tyson and his crime, Tyson was once a hero of mine, and that colored the way I read his darkest thoughts and admissions in Undisputed Truth. I remember driving for hours to get a copy of the Nintendo game Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!!, listening to my French-born, son-of-Eastern-European-Jews father (who often used boxing metaphors to describe his own postwar Jewish immigrant experiences) talk at length about how Tyson was the greatest boxer he’d ever seen, how Tyson was something more than a human: he was a machine.

This man who put on a pair of gloves and decimated people for a living was little more than a piece of an industry erected to cause pain. And while there was never much focus on celebrating the suffering of his opponents, Tyson’s ascension to the rank of Undisputed Champion in the late 1980s meant that he was an exceptional cog in the boxing machine, and an example of how one might make it in the business. The way Tyson would protect himself from head shots, moving side to side, hiding his face behind his gloves or against his massive biceps, then exploding, the velocity of one single punch with a speed and force that didn’t seem real, stunning or outright knocking out his opponent. As a child I learned to appreciate art through observing the way my father appreciated Mike Tyson’s ability to hurt somebody.

That’s what I had to contend with in reading Undisputed Truth, which is, without a doubt, one of the grittiest and most harrowing memoirs I’ve ever read. I am interested in Tyson — his life, his fall from grace, and his subsequent resurrection — because of what he once meant to me and a generation of fans. This book requires us to broaden our understanding of Tyson’s rape conviction with a comprehension of his lifelong victimization at the hands of a system that set him up to lose, and people who profited off of him — figures like Don King, about whom Tyson writes, “When I think about all the horrific things that Don has done to me over the years, I still feel like killing him.” Undisputed Truth won’t (and shouldn’t) change your mind about Mike Tyson, but if you can stomach his frank descriptions of his life, times, and crimes, then it will almost certainly help you understand how the hero so many of us grew up revering became the disturbing and divisive figure he is today.