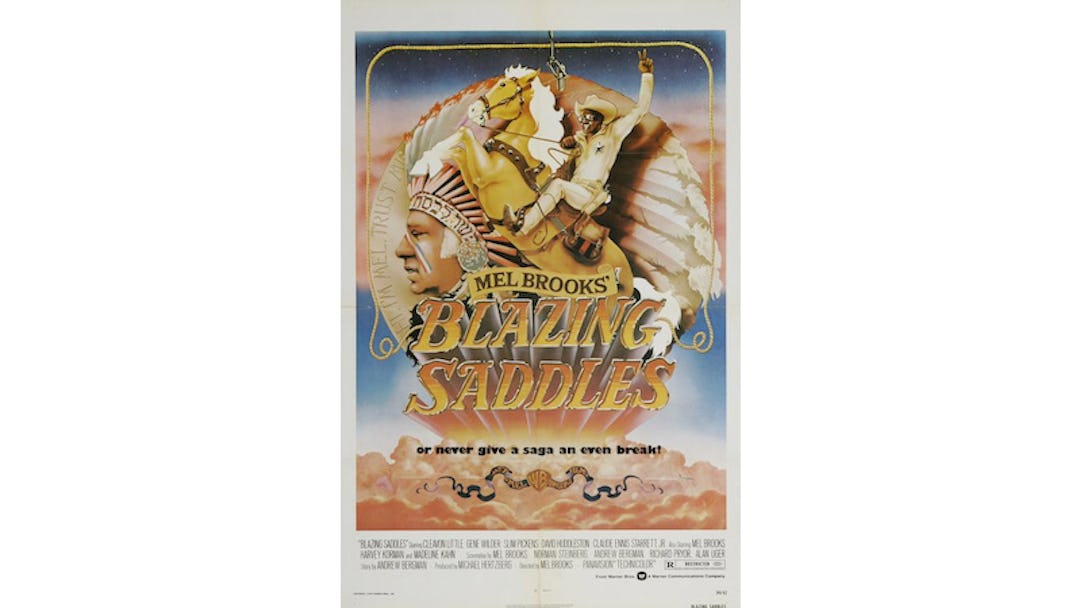

For more than two decades now, the term “politically correct” has been, almost exclusively, the go-to refrain for reactionary scum and regressive cultural conservatives, bellowing self-righteously at the civilization’s hardheaded refusal to let them share their rape jokes or race gags or “feminazi” screeds in peace. Such complaints usually take a tone of wistful nostalgia, longing for a time when the “Thought Police” weren’t on constant patrol (and, thus, white men could pretty much do whatever they damn well pleased), so it’s with some care and concern that we take up the topic of one of the great comedy films, Blazing Saddles, which turns 40 years old this week. It is a film that, by almost any reasonable standard, is “politically incorrect”. But its genius, then and now, was the manner in which director Mel Brooks and his writers turned a broad Western spoof into what was, for its time, a revolutionary satire of race relations.

A bit of background, if (shame on you) you’re unfamiliar with the film: Blazing Saddles is set in the Old West, in the town of Rock Ridge, which has been targeted by the local railroad. A corrupt politician named Hedley Lamarr (Harvey Korman) wants to get his hands on the town’s land before the railroad buys it up, so he figures he can drive out the small-minded locals by appointing Bart (Cleavon Little), a black railroad worker on his way to the hangman’s noose, as their sheriff. The town is, to put it mildly, unwelcoming, but after Bart becomes friends with local legend The Waco Kid (Gene Wilder) and tames the savage Mongo (Alex Karras), he joins forces with the townfolk to keep Lamarr’s villainous scourges at bay.

Now, some context: In spite of tremendous political and social upheaval, race relations were still barely up for discussion in mainstream cinema. Sidney Poitier had carried the torch for much of the 1960s, but his two most explicitly race-themed pictures, In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, were only seven years in the rearview when Blazing Saddles was released in February 1974. Shaft and Super Fly had kicked off the “blaxpoitation” movement in 1971 and 1972, respectively — but those films were geared primarily to a black audience (and they certainly found one). What Blazing Saddles brought to the discussion was a film with a black hero, aimed at white audiences, that was primarily about bass-ackwards white racism. It was a movie that laughed with its black protagonist, and laughed at the crackers who got in his way.

And it was a comedy that used what we now carefully refer to as “the n-word.” It is used frequently and freely; it is used in casual dialogue and it is used as a punch line. But it’s not used for shock value — it is used as it would have been used at the time, and, as Brooks explained, “to show racial prejudice. And we didn’t show it from good people, but from bad people who didn’t know any better.” Still, Brooks was smart enough to know he could both cover his bases and come up with a richer movie by getting an African-American voice on the page, and that was how Richard Pryor got involved.

The film was originally devised as a script called Tex X, by a young screenwriter named Andrew Bergman (who later wrote and directed The Freshman and Honeymoon in Vegas, among others). His idea, in a nutshell, was “H. Rap Brown in the Old West,” and the film nearly came together in 1971 with Alan Arkin directing and James Earl Jones in the leading role. But when that project fell apart, the script went into turnaround, which was how it landed on Mel Brooks’ desk. Brooks was in a career funk; though he’d won the Oscar for The Producers, that award hadn’t translated to box office, and his follow-up The Twelve Chairs had flopped badly. He wasn’t all that interested in directing someone else’s script, but his son Max (who would go on to write World War Z) had just been born, and he needed a job.

Brooks got the idea of rewriting Bergman’s screenplay the way he used to write sketches on Your Show of Shows: get a bunch of funny people in a room, get them going, trying to top each other, and just bang it out. He put Bergman in that room, along with a lawyer-turned-writer named Norman Steinberg and his writing partner, a dentist-turned-writer named Alan Uger. But Pryor was the key. He was still a rising young comic (his breakthrough album, That Nigger’s Crazy, came out three months after Blazing Saddles), but his style and voice were firmly in place: he was talking on stage, openly and without boundaries, about matters of race. He was breaking apart stereotypes and assumptions. He was laughing at white people, and white people were laughing along with him.

One would assume that Pryor was mostly responsible for the race-based humor in Blazing Saddles, but Brooks has emphasized that it wasn’t nearly as simple as that. In recent documentaries about both himself and Pryor, he’s said that Pryor’s primary interest was in the character of giant simpleton Mongo (“Mongo only pawn in game of life”); elsewhere, he’s said, “Pryor wrote the Jewish jokes, the Jews wrote the black jokes.” In other words, it wasn’t a matter of who wrote what; it was that with Brooks allowing the ship to go anywhere, and a visionary comic voice like Pryor contributing (and, it seems, serving as a kind of permission slip to go wherever the story might take them), anyone could write anything.

That “anything goes” spirit resonates throughout Blazing Saddles, a comedy that throws everything at you: nonsensical wordplay, Jewish references, wild sight gags (the hangman stringing up a man in a wheelchair, or both a man and the horse he sits atop), leering, historical anachronisms, scatology (the famed “baked beans” scene, which isn’t about farts, but the sheer volume of them), cheerful vulgarity (a hymn that ends “our town is turning into shit”), genre conventions, celebrity parody (via Madeline Kahn’s uproarious Marlene Dietrich vamp), Keystone-style slapstick (there’s a pie fight, for God’s sake), and breaking the fourth wall — most famously in its climax, which follows the action right off the Warner lot and to a screening of Blazing Saddles at Grauman’s Chinese.

(Side note: it is by now part of the film’s legend that Brooks badly wanted Pryor to play the lead role of Bart, and that he was vetoed by Warner brass, who were worried by both Pryor’s minimal film experience and reputation as an unreliable wild man. Poor Cleavon Little, who is very good in the film, will be forevermore compared to the Pryor performance that could have been — a hypothetical that is cruel not only when imagining what he could have done with Pryor-esque bits like that first scene in Rock Ridge, but when noting that it would have paired him with Gene Wilder two years before Silver Streak, the first of their four film collaborations.)

Yet the film’s primary satirical target, even more than the Panavision Technicolor vistas of the American Western, is racism, and how it is the intellectual property of “simple farmers… people of the land. The common clay of the new West. You know… morons.” As Brooks promises, those who call Bart the n-word are mouth-breathing morons, ignorant hillbillies who share their saloon and town council meetings with cows. Bart, on the other hand, is smart, funny, and handsome, a Gucci saddlebag-sporting cool customer. “What’s a dazzling urbanite like you doing in a rustic setting like this?” asks the Waco Kid, not unreasonably; when Bart outsmarts the town by taking himself hostage at his welcoming ceremony, he tells himself, “You are so talented, and they are so dumb.”

That dichotomy is established early, when Bart is still a railroad worker, and Taggart (Slim Pickens) asks the crew to regale him with “a good ol’ nigger work song.” Bart and his colleagues respond with a golden-throated rendition of the very white Cole Porter’s “I Get a Kick Out of You,” which Taggart interrupts with the suggestion of “Camptown Races” (which he incorrectly dubs “Camptown Ladies”). The title prompts puzzled looks and confusion from the crew, so Taggart and his gang perform it for the workers, who proceed to watch their supposed betters sing and dance, and barely stifle their laughter.

That dynamic is all the more apparent in Blazing Saddles’ only genuinely offensive scene, which comes near the end, during the film’s raucous takeover of the WB lot. The climactic fight scene spills onto the set of a tux-and-tails musical, where the mincing director and hissing, “sissy” dancers are thrown into the action. It’s a wince-inducing scene on its own, but a sharp and valuable contrast to the rest of the film — because this is a scene of just pointing and laughing at a minority. Because it did that wrong, we can fully appreciate what the rest of the movie does so right.

But Blazing Saddles doesn’t just laugh at racism and leave it at that. Perhaps the most quietly poignant scene in the picture comes after Bart begins to win over the town by taking down Mongo with a Looney Tunes-style exploding Candygram (the toughest part, he later explains, was “inventing the Candygram… they probably won’t give me credit for it”). The sweet little old lady who earlier greeted him with an odious “Up yours, nigger!” brings him a warm pie as a thank you, and they exchange pleasantries. Moments later, she returns with an additional request: “Of course you have the good taste not to mention that I spoke to you?” If, as Brooks said, “the Jews wrote the black jokes,” that feels like one that had to have come from Pryor: an acknowledgement, as in the best of his work, that it’s all good and well to laugh at this stuff, but there’s real pain there too.

Blazing Saddles is available for streaming on Amazon and iTunes.