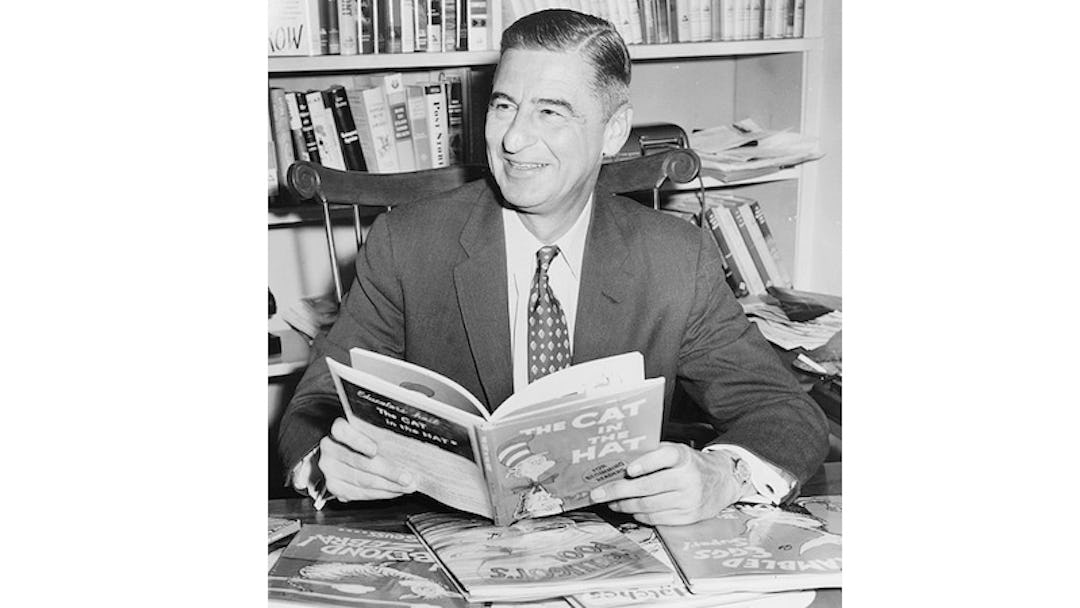

A wizard of the written word, today marks the birthday of Theodor Geisel — better known as the dear Dr. Seuss. The beloved children’s author and illustrator created a menagerie of creatures that recited anapestic tetrameter, caused trouble, and captured our imaginations. The man behind beasties like the Grinch, Lorax, and Sneetches was a fascinating character in his own right. Here are 20 facts about the great Dr. you might have missed.

Geisel adopted his famous moniker after getting kicked off the staff of Dartmouth College’s humor magazine, the Jack-O-Lantern. He was caught drinking bootleg gin with his pals and was forced to resign from extracurricular activities at school. He started signing his work with the pen name “Seuss” to hide it from his editor.

Geisel almost earned his doctorate in English literature, but left Oxford to travel Europe and sow his artistic oats. Dartmouth awarded Geisel an honorary doctorate in 1956, and he added “Dr.” to his pen name as a way to acknowledge his father’s dreams for him.

A known perfectionist, Geisel would sometimes spends months or even up to a year creating a book. Despite this, he somehow found time to write over 45 children’s books during his colorful career.

Shockingly, Geisel never won the Caldecott or Newbery Medals. He was recognized with the Caldecott Honor three times: McElligot’s Pool (1947), Bartholomew and the Oobleck (1949), and If I Ran the Zoo (1950).

Thanks to his love of language, Geisel is usually credited with inventing the word “nerd.” It appeared in his 1950 book, If I Ran the Zoo. However, it wasn’t popularized as a slang term until the 1960s.

Seuss’ style became part of the pop culture landscape as early as the 1920s when Standard Oil of New Jersey hired the artist for an ad campaign that caught on with the national public. The product? A bug spray called Flit. The slogan, “Quick, Henry, the Flit!” was spoofed by popular comedians of the time, such as Jack Benny. The successful ad led to work in magazines like Vanity Fair and with major companies, including NBC and General Electric.

Some of those early ads featured beasts with tongue-twisting names, similar to the creatures he would become famous for. Geisel’s freshman creature lineup included the Ero-doccus, a Karbo-nockus, a Moto-raspus, and a Moto-munchus.

In the 1940s, Geisel supported the war effort by designing posters for the Treasury Department and the War Production Board. He joined the army as a captain in 1943, oversaw the Animation Department of the First Motion Picture Unit, and created a number of training films and propaganda movies. Design for Death and Gerald McBoing-Boing (produced by the United Productions of America, which made the World War II training films) won Academy Awards.

Suess drew over 400 political cartoons for leftist New York City daily, PM.

Geisel’s only foray into feature filmmaking was with 1953’s The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. He wrote the screenplay and lyrics. The movie about a young, reluctant pianist who retreats into a music-filled dream world bombed.

Geisel and second wife Audrey Stone Dimond had no children. “He was afraid of children to a degree,” Audrey Geisel said in a 2004 interview. He found them unpredictable. “What might they do next? What might they ask next?” he would joke. “No, he couldn’t just sit down on the floor and play with children. It was none of that. He just had to do what he had to do, and they loved him. And he loved them for loving what he did,” Audrey revealed.

While there were no children in the Seuss clan, he did make up imaginary little ones to brag about when his friends boasted about theirs. “Chrysanthemum Pearl” was probably the “daughter” he discussed the most. She was precocious imaginary child, capable of making “the most delicious oyster stew with chocolate frosting and flaming Roman candles.” Other mythical kids included Norval, Wally, Wickersham, and Thnud. Geisel even signed their names on the family holiday cards.

The Cat in the Hat author is said to have owned hundreds of hats that he kept stashed away in a secret closet. He enjoyed showing them off at dinner parties.

Geisel was a smoker (he died of oral cancer). Once when he tried to quit, he planted strawberry seeds, peat moss, and radish seeds in his pipe and watered it with a medicine dropper every time he craved a puff.

Geisel greatly admired the work of children’s author and illustrator Maurice Sendak and appreciated his “adult” approach to subjects. He once said that he if he were a child, he’d be reading Sendak.

Green Eggs and Ham contains only 50 words and was written on a bet. Publisher Bennett Cerf didn’t think Geisel would be able to create a story with fewer words than The Cat in the Hat — which featured only 225 words.

“And that is a story that no one can beat / And to think that I saw it on Mulberry Street,” are the signature lines of the 1937 book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. Geisel was inspired by the rhythm of a ship’s engine during a voyage to Europe with his wife and conceived of the story’s style during their vacation. The book was rejected 20 times before hitting the presses.

The author was fond of felines and considered his donation to the San Diego Wild Animal Park in California, used to build the lion wading pool, one of his greatest accomplishments.

Geisel found it tiresome and difficult to answer the question: “Where do your ideas come from?” He responded in a very Seussian way: “I get all my ideas in Switzerland near the Forka Pass. There is a little town called Gletch, and two thousand feet up above Gletch there is a smaller hamlet called Über Gletch. I go there on the fourth of August every summer to get my cuckoo clock fixed. While the cuckoo is in the hospital, I wander around and talk to the people in the streets. They are very strange people, and I get my ideas from them.”

The last line in Geisel’s final book, Oh, the Places You’ll Go!, reads: “You’re off to great places! Today is your day! Your mountain is waiting. So… get on your way!”