Restless Books/ Amazon

“Un oiseau chante d’autant mieux qu’il chante dans son arbre généalogique.” Or, “A bird sings best in its genealogical tree.” This reflection from Jean Cocteau introduces us to The Holy Mountain and El Topo director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s mythic memoir, Where the Bird Sings Best.

During his recovery from an opium addiction, under the influence of French philosopher Jacques Maritain, Cocteau made a fleeting return to the Catholic Church. “Art for art’s sake, art for the masses, it’s all equally absurd. I propose art for God,” Cocteau declared. Allies of a parallel “divine” counterculture and kindred poet-magicians, Cocteau wrote the introduction for Jodorowsky’s directorial debut — 1957’s La cravate, a mime adaptation of Thomas Mann’s novella The Transposed Heads, starring the filmmaker.

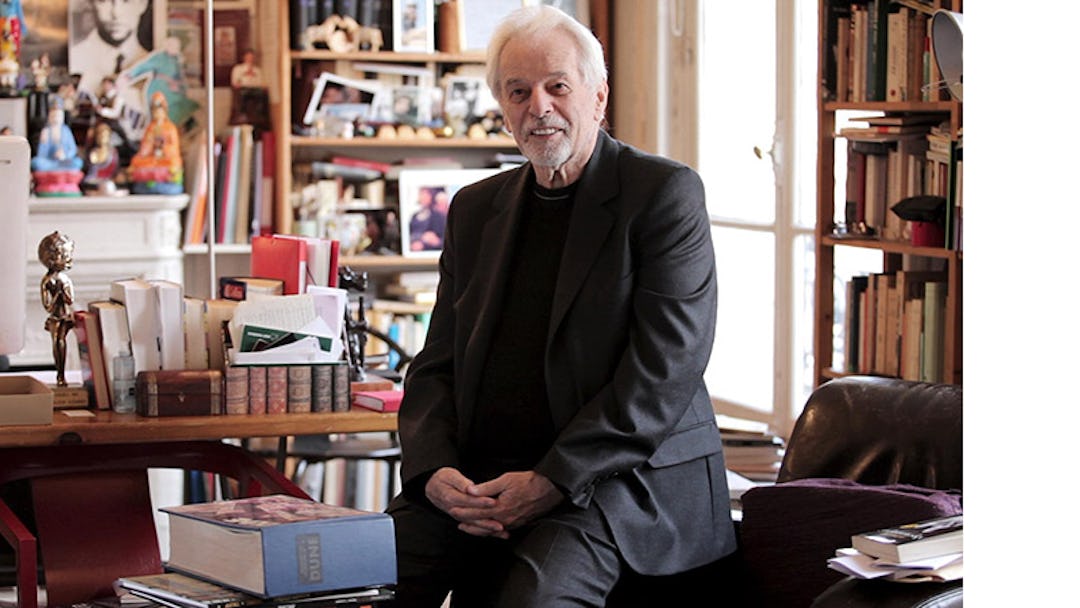

For his latest movie, The Dance of Reality , Jodorowsky returned home to the Chilean town of Tocopilla. Where the Bird Sings Best, translated in English for the first time, is a novelization of this journey — a sweeping tale of personal, philosophical, and political struggles. It’s an immigrant’s story of Fellini-esque proportions. “Our genealogical tree is the trap that limits our thoughts, emotions, desires, and material life, but it is also the treasure that captures the greater part of our values,” he writes. For the self-proclaimed atheist mystic, the sacraments are memory, dreams, family, wisdom, the grotesque, and the reinvention of the self.

Publisher Restless Books reminds us that during Jodorowsky’s decades-long absence from cinema, he maintained his status as a notable Latin American novelist. They will also publish the first English translations of two other popular Jodorowsky novels: El niño del jueves negro (The Son of Black Thursday) and Albina y los hombres perro (Albina and the Dog Men) — a “sprawling modern myth in which sexual desire appears as a dangerous and generative force that mutates and transforms, unraveling identities and rending the social and moral fabric of a small town.”

Jodorowsky’s multilingual bibliography weaves together a rich tapestry of influences and obsessions. His fictional works evoke the surreal images in his films. Non-fiction titles explore psychomagic, a shamanic form of therapy that relies on the healing power of dreams, art, and theater. “The only words that interested me were those of poetry, because they were proposing, tragically, to attempt to explain silence,” he told Frieze in 2013. A Spanish-language collection of his unpublished texts and poetry, the cornerstone of his fabled works, was released last year.

His fascination with the tarot started when he was 20. But it wasn’t until years later when he met Surrealist icon André Breton, who introduced him to the influential Tarot de Marseille, that he became a published scholar on the subject. This led to his restoration of the 78-card deck with Philippe Camoin. The Camoin family have been the keepers of the Tarot de Marseille since the 19th century.

An enviable congregation of collaborators and mentors guided Jodorowsky in his writing and performance work amongst the Panic Movement — a shocking, absurdist theater collective inspired in part by Luis Buñuel and Antonin Artaud. Jodorowsky co-founded the group with Spanish playwright Fernando Arrabal and French artist Roland Topor. Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington became one of many “wisewomen” in Jodorowsky’s life, taking him on as a theater and spiritual apprentice. He staged her play Penelope in 1957 (pictured), but by night he was entranced by the artist, drinking her blood during cryptic rituals, heeding her call in his dreams. No stranger to controversy, Jodorowsky’s 1961 adaptation of Strindberg’s Ghost Sonata and 1962 play La ópera del orden (The Opera of Order) were censored by the government.

Humanoids, Inc./ Amazon

In 1966, Jodorowsky created his first comic strip, Anibal 5, two years before directing his first feature film — the scandalous Fando y Lis, which provoked a riot during its Mexican premiere. Yet graphic novels are an aspect of his career that have been largely overlooked. “In France comic strips are regarded as a serious art form, and whole stores are devoted to hard-bound collections of them. Jodorowsky is to French comics what Camus is to French literature,” Roger Ebert wrote in his 1989 interview with the filmmaker. Our perception of comics has changed since then, but Jodorowsky’s strange, visionary works still take a backseat to caped crusaders — at least on American shores, where they receive sporadic translations. In many ways, the world of graphic novels has offered the director the best of everything: a platform for wild visuals and experimental writing. A pulp objet d’art.

Humanoids, Inc./ Amazon

Prestigious European graphic novel publisher Humanoids has issued the bulk of the Jodorowsky comic canon. He has collaborated with legendary artists like Jean “Moebius” Giraud, Juan Giménez, and Milo Manara to create elaborate, heady serial narratives. His most influential works, the Metabarons and Incal stories, take place in a shared fictional universe. The protagonists were introduced in The Incal, but conceptually they borrow liberally from Jodorowsky’s unrealized Dune adaptation. The Metabarons narratives center on the oft-damaging inheritances that are passed on through generations (ideologies, revenge, greed)—not unlike the familial traumas his psychomagic practices seek to uncover.

As with Where the Bird Sings Best, Jodorowsky’s non-film works are conduits and biographical keys that further reveal his mesmerizing process of imaginative self-fashioning.