We’re coming to the close of a great retrospective of Joe Sarno’s works at New York’s Anthology Film Archives, ending September 26. Sarno was one of the sexploitation genre’s key auteurs, and his films evoke the independent spirit of the underground film movement — movies popularized during the ‘60s that pushed the boundaries of technique and narrative with experimental artistry. These pictures produced outside the commercial moviemaking industry ranged from the subversive to the formless (at least where any story was concerned), delighting in explicit subjects and exploring radical in-camera editing. Crucial as he is, Sarno is just one of these 50 underground filmmakers you should know.

Jack Smith

“The only person I would ever copy. He’s just so terrific, and I think he makes the best movies,” said Andy Warhol of underground filmmaking legend Jack Smith. The influential fringe director challenged gender and sexual norms, and introduced a controversial and delirious camp-trash aesthetic that has been copied by artists and filmmakers like Mike Kelley and John Waters, to name a few. Smith’s 1963 film Flaming Creatures was ruled to be “obscene” and confiscated by the police during its premiere at New York’s Bleecker Street Cinema. Susan Sontag described it as a “rare modern work of art; it is about joy and innocence.”

Birgit Hein

Women are too often presented as the less-important halves of filmmaking couples, but German writer-director Birgit Hein managed to establish a presence apart from her frequent collaborator, husband Wilhelm Hein. Several of her films broached the subject of collective female anxiety. “That’s what’s interesting in these trash films — the horror and prison films — they’re not reality,” Hein stated in a 1990 interview. “These films deal with dreams and somehow they are true in a psychic way. If women can act like this in a film, it means society also believes they can do that.”

The Kuchar brothers

Twin prodigies George and Mike Kuchar produced a slate of inventive 8mm films during the ‘60s and ‘70s that caught the eye of underground legends like Andy Warhol, Ken Jacobs, and Jonas Mekas. In an astute nod to Hollywood’s Golden Era, the Kuchars employed a heady blend of B-cinema, avant-garde narrative, queer-camp melodrama, and radical social critique. George later produced a series of verité Hi8 video diaries — a poignant record of his daily life. His best-known work, Hold Me While I’m Naked, is an autobiographical portrait of a frustrated artist.

Timothy Carey

“You can’t leave the film industry to the money people, they degrade it, they make people nothing,” said wild-eyed filmmaker Timothy Carey. Better known for his astounding roles in John Cassavetes’ Minnie and Moskowitz and The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, and Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing and Paths of Glory, Carey cut his own path through ’60s cinema. Directing only a handful of features, Carey made an indelible impression on the underground with 1962’s The World’s Greatest Sinner (featuring a score from then unknown Frank Zappa), which he also wrote, starred in, and produced. “I was tired of seeing movies that were supposedly controversial. So I wanted to do something that was really controversial,” he said of Sinner — about an insurance salesman who grows tired of his mundane life, starts a cult, appoints himself God, and starts a band. A taboo critique of religion, politics, and middle-class America, Carey’s work was buried for years by the “money people,” but his audience knows better.

Bruce Conner

From LA Weekly‘s remembrance of the San Francisco found-footage pioneer:

A Kansas native who studied art at Wichita University and eventually settled on the West Coast, Conner first caused a stir in the gallery world in the late 1950s, with a series of controversial assemblages (one of which, now in MoMA’s permanent collection, featured a sculpture of a screaming child bound by nylon stockings to a highchair). But it’s Conner’s film work—the subject of a two-night retrospective co-presented by the UCLA Film & Television Archive, REDCAT and Los Angeles Filmforum—that has cast the longest shadow, spanning six decades, and stretching from Conner’s San Francisco studio to the foothills of Hollywood. While future YouTubers were in the womb (or not even a thought in their parents’ heads), Conner saw the potential of throwaway images—movie countdown leaders, industrial films, TV commercials, softcore porn—to be forged into dazzlingly associative montages, rhetorical loops or subliminal blurs designed to dance upon the audience’s subconscious. MTV, it has been said, might never have existed without him.

Sarah Jacobson

Jacobson’s underground splatter short I Was a Teenage Serial Killer was featured in our 50 Essential Feminist Films list:

To me, feminism means that I should have an equal opportunity to do what I want to do as a woman. I don’t want to be better than men, I don’t want to shut men up. It’s like, look, you’ve got your little thing over here, you’ve got your B-movie aesthetic, and I’ve got my interpretation of it that girls can enjoy, too, so you don’t always have to watch the bimbo get raped or slashed or stalked or whatever.

Author of the progressive S.T.I.G.M.A. Manifesto (Sisters Together in Girlie Movie-Making Action), Jacobson left behind a gender-busting DIY legacy that continues to empower independent filmmakers.

Kenneth Anger

Before David Lynch featured Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet” in his 1986 movie, Kenneth Anger used it in the groundbreaking 1963 film Scorpio Rising — which toyed with notions of rebel worship and the Hollywood ideal through queer, occult imagery. “Scorpio Rising inaugurated innovative representations of same-sex desire through its cinematic juxtaposition of such mass-mediated images. Moreover, its montage often playfully foregrounds contradictory conceptions of same-sex desire that continue to influence our thinking about sexuality and identity today,” writes the journal Genders. Anger’s influence is incalculable. Provocative as ever, his website greeting encapsulates the spirit of his work:

DESPITE INFLUENCING THE LIKES OF SCORSESE AND LYNCH, THE GROUNDBREAKING CINEMA OF RENOWNED OCCULTIST KENNETH ANGER HAS REMAINED UNDERGROUND FOR DECADES. DO YOU, FILM-WATCHER, HAVE MORAL COURAGE? DO YOU HAVE INTELLECTUAL HONESTY? ARE YOU NOT UTTERLY BENT SPIRITUALLY UNDER THE JUDEO-CHRISTIAN AMERICAN YOKE, JUICY PREY, LAMB OF THE FOLD OF THE SLAVES OF THE SLAVE GODS? IN SHORT, IS THERE MANHOOD IN YOU YET? THEN WATCH THESE FILMS, IF YOU WILL, AND MEET THE MOST MONSTROUS MOVIEMAKER IN THE UNDERGROUND. MEET KENNETH ANGER.

Herschell Gordon Lewis

Known as the “Godfather of Gore,” Herschell Gordon Lewis’ assault on good taste pioneered the splatter subgenre and established him as an exploitation icon through a series of shocking, blood-soaked pictures. 1963’s Blood Feast is considered the first gore film. Capturing his images in lurid Eastmancolor, Lewis depicted gruesome acts with cringe-worthy realism (using real animal organs for flesh-ripping scenes). His work is also synonymous with various publicity stunts — such as the “vomit bag,” which was handed to moviegoers upon entering theaters.

William Castle

John Waters’ glowing praise for B-movie legend William Castle (House on Haunted Hill, The Tingler, 13 Ghosts) is fun reading:

Without a doubt, the greatest showman of our time was William Castle. King of the Gimmicks, William Castle was my idol. His films made me want to make films. I’m even jealous of his work. In fact, I wish I were William Castle. . . . William Castle was the best. William Castle was God.

Paul Morrissey

Bright Lights Film Journal founder Gary Morris wrote a must-read essay on the work of Andy Warhol collaborator Paul Morrissey — one of the driving forces behind the Factory’s film output:

Much of the myth, if we can call it that, surrounding Paul Morrissey comes out of his early relationship with Andy Warhol’s Factory and its glittering, damaged denizens. In a world of stylized weirdos, Morrissey was the straight businessman, always looking for the commercial possibilities inherent in a scene where few believed any existed. Viva called him “a real nine-to-fiver” and Warhol biographer Stephen Koch said he was “an anomaly at the Factory.” Morrissey’s drive and ambition made it possible for him to rework the Warhol aesthetic evident in conceptually rich but unbearably dull experiments like Sleep and Empire into more accessible, coherent, and committed works like Trash, Heat, Mixed Blood, Blood for Dracula, and Women in Revolt. The “great film achievements” of Warhol belong, for the most part, to Morrissey, who wrote, produced, and directed them while Warhol contributed no more than his name above the title.

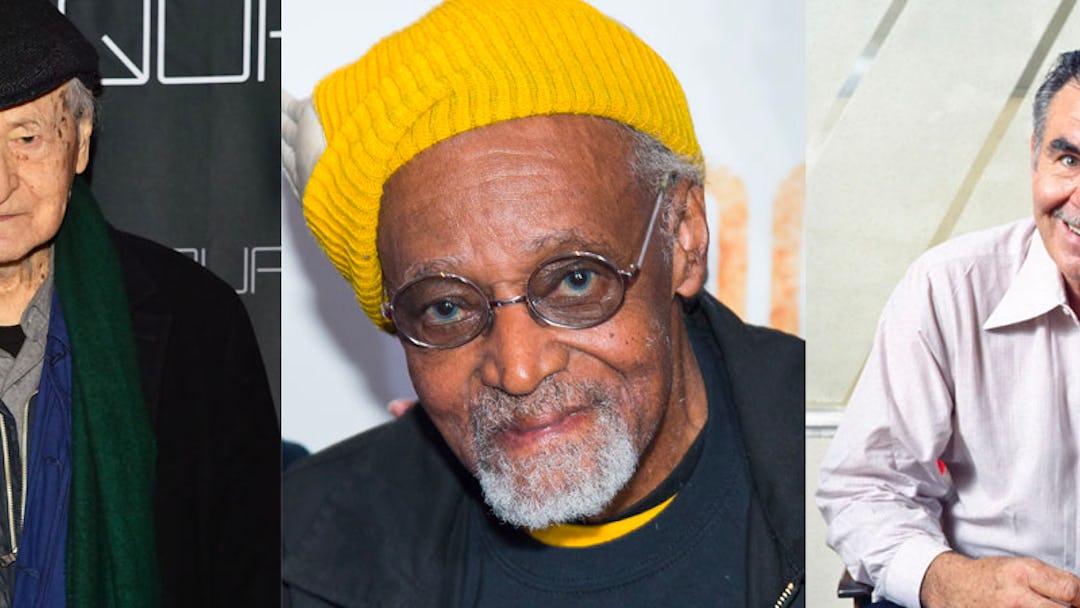

Photo by Charles Sykes/Invision/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Melvin Van Peebles

“Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song gave us all the answers we needed. This was an example of how to make a film (a real movie), distribute it yourself, and most important, get paid. Without Sweetback who knows if there could have been a She’s Gotta Have It, Hollywood Shuffle, or House Party?” said Spike Lee of director Melvin Van Peebles, father of actor and New Jack City director Mario Van Peebles. The elder Peebles wrote, produced, scored, marketed, and starred in the groundbreaking 1971 film — which featured an all-black cast and unsimulated sex scenes, and heralded a wave of copycat movies, leading to the formation of the blaxploitation genre. Repeatedly rejected by the studio circuit, Peebles financed the film himself with help from Bill Cosby.

Storm De Hirsch

“I wanted badly to make an animated short and had no camera available. I did have some old, unused film stock and several roles of 16mm. sound tape. So I used that — plus a variety of discarded surgical instruments and the sharp edge of a screwdriver — by cutting, etching, and painting directly on both film and tape,” poet and New York avant-gardist Storm De Hirsch told Jonas Mekas of her film Divinations in a 1964 interview. Her written work and interest in Eastern esoterica informs her improvisational shorts.

Scott B and Beth B

East Village No Wave figures Scott B and Beth B (and their pun-tastic production company B Movies) achieved cult status through a series of raucous 8mm shorts — “savage satire on society’s distortions.” Their works caught the early attention of experimental film aficionados like J. Hoberman (who called them “space-age social realists” in 1979) and saw collaborations with a veritable who’s who of New York artists: Richard Prince, Lydia Lunch, and Bill Rice. Beth B. continued to make movies after parting ways with Scott (noise-noir Vortex is considered the last No Wave movie by many). She found modest mainstream success with the films Salvation! and Two Small Bodies.

Shûji Terayama

Prolific anarchist Shûji Terayama was a key figure in radical filmmakers’ group the Art Theatre Guild and the founder of avant-garde theater troupe Tenjo Sajiki — for which he was praised by critic Akihiko Senda as being “the eternal avant garde.” 1971’s Emperor Tomato Ketchup and 1974’s Pastoral: Hide and Seek found Terayama championing a post-adult world populated and ruled by orgy-loving youths. Terayama also wrote the “runaway” movement’s unofficial manifesto in Throw Away Your Books, Rally in the Streets, a blistering adaptation of his own play.

Photo by Andrew H Walker/REX/Shutterstock

Jonas Mekas

The Guardian on “godfather of the avant-garde” Jonas Mekas:

Mekas is an integral figure in the history of what used to be called underground cinema, not just as a film-maker, but as a writer, a curator and a catalyst. In 1969, he helped set up the Anthology Film Archives in New York, which houses the most extensive library of experimental films in existence, and he has since overseen the restoration of many classics of the form. His conversation is peppered with the names of the more famous people he worked with in the golden age of avant-garde film-making in the 1960s, from Yoko Ono to Jackie Kennedy, Allen Ginsberg and the Beats to the Warhol set. Many of these figures ended up in his films, which have in turn influenced the likes of Jim Jarmusch, Harmony Korine, John Waters and Mike Figgis.

Stan Brakhage

Robin Blaetz’s Avant-Garde Cinema of the Seventies essay is a nice primer on the time period for the uninitiated, with emphasis on the titan of experimental cinema, Stan Brakhage:

Stan Brakhage, who started making films in the 1950s and is the best known and most prolific filmmaker of the American avant-garde, continued his influential work throughout the 1970s. His signature first-person use of the camera, in which the movement of the apparatus defines consciousness itself, was expanded from documenting immediate perception to recording the filmmaker’s encounter with memory and the world at large. Brakhage himself best described his lifelong project in the opening lines of his often-reprinted manifesto of 1963, entitled Metaphors on Vision: “Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception…. Imagine a world before the ‘beginning was the word.” This union of body and camera that records the very process of experiencing the world regardless of all established codes of visual language is inherently documentary. Brakhage’s work as an editor was to join and layer what he had discovered in the world, to suggest in a single work of art the endless correspondences in and the richness of perceptual experience. Since Brakhage’s films, which range in length from minutes to many hours, manifest neither thematic unity nor recognizable technique, they are virtually indescribable. However, they reflect the concerns of the seventies to the degree that they use the world as raw material, yet eliminate all recognizable imagery through abstraction.

Ian Hugo

Watch Ian Hugo’s film Bells of Atlantis, starring Hugo’s wife Anaïs Nin as the mythical narrator, reading from her dream-laden novella House of Incest. The short features a score by electronic musicians Louis and Bebe Barron (Forbidden Planet). Reminder: this was bloody weird stuff for 1952.

Photo by Jens Kalaene/EPA/REX/Shutterstock

Werner Schroeter

Film Comment on the queer German underground director (and nihilist fashionista!) Werner Schroeter:

Like his contemporaries Fassbinder, Herzog, and Wenders, the late Werner Schroeter was one of the New German Cinema’s seminal figures, if far more marginal in terms of recognition. He started out as an underground filmmaker in 1967 before making a critical impact on the international festival circuit and winning a devoted cult following. His films, shot through with a predilection for operatic excess and artifice, defy categorization, and are infuriatingly obscure for some and entrancingly poetic for others. His cinema occupies a transitional space between avant-garde and art cinema, neither quite narrative nor quite abstract. In the second half of the Eighties he became widely known as a theater and opera director, staging a range of hyperstylized productions in Germany and abroad that outstripped even his films in their ability to provoke both intense admiration and hostility. His flamboyance and reputation for refusing to compromise with the mainstream attracted outstanding talents willing to work for little or no money, some of whom became his regular collaborators. Foremost among the performers was Magdalena Montezuma, the splendid German underground star and Schroeter’s muse until her death in 1985. Subsequently French stars such as Bulle Ogier, Carole Bouquet, and Isabelle Huppert gave him an additional art-house aura. Throughout his career and thanks to major retrospectives, including events in London, Paris, and Rome, Schroeter’s films kept garnering new, if select, audiences.

Bette Gordon

“Christine (Sandy McLeod) takes a job selling tickets at a porno theater near Times Square. Instead of distancing herself from the dark and erotic nature of this milieu, she develops an obsession that begins to consume her life. Few films deal honestly with a female sexual point of view, controversial and highly personal, Variety does just this,” writes IMDb of Bette Gordon’s best-known feature (1983). Gordon’s work was born out of the downtown New York punk scene, and her contributions to the feminist film milieu have been under-appreciated. Here’s a nice little intro to Gordon, written by the director, that focuses on her not-so-underground 2009 film Handsome Harry.

Christopher Maclaine

I highly recommend reading these 1986 interview excerpts from thee Stan Brakhage on influential beat filmmaker Christopher Maclaine, whose fascinating career ended tragically after he was committed to an asylum:

Christopher was considered the Antonin Artaud of North Beach, which was a fiercer place, I’d fancy, than Paris was in Artaud’s time. North Beach was a place of great despair, World War II despair. So many veterans came back and found the nation they had gone to defend had eroded from their idealist viewpoints into the drive for the almighty dollar—(in) the “booming” postwar period … This was a great disillusionment. Many of them pitched into this despair — the driving back and forth across the country, the drinking, or if they had no money, just drinking and sitting in the gutter. Chris was one of the first to read his poetry, often to jazz music, in bars to get his drinks for the evening, or a meal. He had a few books of poetry in print, one of which I’m fortunate to still have a copy of… I don’t know how in the world he decided to make film because the lifestyle he led wouldn’t usually enable him to do so. It wasn’t that he was that much of an oddball — he was just the king of an accepted form of insanity… So Maclaine made these four films (THE END, THE MAN WHO INVENTED GOLD, BEAT, and SCOTCH HOP) in a burst of energy in the early ’50s, culminating in THE END, which had its world premiere at Frank Stauffacher’s Art in Cinema, where it precipitated a riot—not as violent as some of the French riots, but there were certainly chairs thrown, and people storming out or screaming for their money back.

Stan Vanderbeek

Vanderbeek’s surrealist collage film works (Terry Gilliam, eat your heart out) found him collaborating with an enviable group of artists, including Claes Oldenburg, Yvonne Rainer, Merce Cunningham, Allan Kaprow, and John Cage. “He called himself a technological fruit picker,” curator Joao Ribas said of the artist. Of his own aesthetic, Vanderbeek wrote:

The technological explosion of this last half-century, and the implied future are overwhelming, man is running the machines of his own invention… while the machine that is man… runs the risk of running wild. Technological research, development, and involvement of the world community has almost completely out-distanced the emotional-sociological (socio-“logical”) comprehension of this technology. The “technique-power” and “culture-over-reach” that is just beginning to explode in many parts of the earth, is happening so quickly that it has put the logical fulcrum of man’s intelligence so far outside himself that he cannot judge or estimate the results of his acts before he commits them.

Marie Menken

“Willard and Marie were the last of the great bohemians. They wrote and filmed and drank — their friends called them ‘scholarly drunks’ — and were involved with all the modern poets,” Andy Warhol said of experimental filmmaking couple, the Menkens. The duo’s vital film group Gryphon (established in the 1940s) saw the couple producing and promoting experimental works, establishing an early foundation for independent cinema. “Marie was one of the first to do a film with stop-time. She filmed lots of short movies, some with Willard, and she even did one on a day in my life,” Warhol also declared. “There is no why for my making films. I just liked the twitters of the machine, and since it was an extension of painting for me, I tried it and loved it,” Menken said in 1966. “In painting I never liked the staid and static, always looked for what would change the source of light and stance, using glitters, glass beads, luminous paint, so the camera was a natural for me to try — but how expensive!”

Photo by Elisa Leonelli/REX/Shutterstock

Russ Meyer

Roger Ebert on friend and collaborator Russ Meyer (Ebert wrote the screenplay for 1970’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls) and what separated the sexploitation pioneer from his flesh-loving peers:

What Meyer’s films also have is an uncommonly high level of artistry. In professional filmmaking circles, Meyer is known as the one creative director in the sexploitation field. His competitors churn out slipshod low-budget films exploiting the nudity of their actresses (who usually look hideous enough to inspire cries of “put it on!”). But Meyer budgets his films at around $70,000—or 10 times the usual level—and rehearses his cast for a month before shooting. . . . His films are limited by their genre (familiarly known as the “skin flick”) and by their budgets, but a consistent artistic vision dominates them. They are fast-paced, usually well-acted, directed with a joyous zest, and they deliver the goods.

Ken Jacobs

In his ’70s, Ken Jacobs made a nearly seven-hour film he started in the late 1950s, Star Spangled to Death, composed of found footage. “It pictures a stolen and dangerously sold-out America, allowing examples of popular culture to self-indict. Racial and religious insanity, monopolization of wealth and the purposeful dumbing down of citizens and addiction to war oppose a Beat playfulness,” writes the filmmaker of his 2004 movie. One look at Jacobs’ filmography shows the tireless, now octogenarian director has made multiple films each year since then. J. Hoberman’s New York Times essay is a lovely introduction to Jacobs’ experimental contributions, which remain shockingly underrated.

Kôji Wakamatsu

Kôji Wakamatsu has over 100 directorial credits to his name and is best known for his confrontational and politically incendiary “pink” softcore films. “Rape was a recurrent trope, usually in a metaphorical role to represent patriarchal oppression and the US military’s involvement in neighbouring countries on the Asian mainland,” writes Jasper Sharp for the British Film Institute. In addition to directing violent “eroductions” with evocative titles like Go, Go Second Time Virgin and Sex-Jack, the filmmaker’s Wakamatsu Pro company produced films like 1976’s In the Realm of the Senses (1976) and 1971’s Red Army PFLP: Declaration of World War, a propagandistic pro-Palestinian documentary.

Gregory Markopoulos

Not even a self-imposed exile during the ’60s kept the visionary works of Gregory Markopoulos under wraps. The Harvard Film Archive celebrates the films of the New American Cinema movement icon:

Gregory Markopoulos (1928-1992) was one of the true visionaries of the post-WWII American avant garde. Across his exquisitely stylized, oneiric early films and through his dazzling master works of the late Sixties and Seventies, Markopoulos defined a unique film language of incomparable formal rigor, visual beauty and haunting lyricism. A tireless perfectionist, Markopoulos crafted a unique mode of art cinema with an astonishingly minimum of funding and resources—often editing his negatives by hand with only razor blade and magnifying glass and perfecting in-camera editing techniques that brought a poetic density to his films. Evident throughout his first major films is a fascination with myth and ritual which would carry across Markopoulos’ later work and would, eventually, call him back to his ancestral Greece. The heady mythopoesis of key early films such as Swain and Twice a Man is also charged with a bold exploration of sexual and homosexual desire that was, in every way, far ahead of its time.

Damon Packard

Los Angeles filmmaker Damon Packard has been experimenting with film since the ‘80s, but his underground opus, 2002’s Reflections of Evil (a film he blew an inheritance on to create and in which he plays the lead role), bridges a B-movie aesthetic with Hollywood formalism. From Casey McKinney:

His heroes are serious, and for the most part, mainstream filmmakers, people like Spielberg at his best moments. And while he may be interested in the look of say Night Gallery, it’s not for the kitsch value. Damon’s simulations of his favorite era are move of a stripped down refinement of the period’s best qualities—explorations of innovative camera techniques and analogue attempts at recreating altered states of consciousness. To mime this look, Damon employs the use of lens flares, slow motion, spot diffusion, mirror props, kaleidoscopic filters, superimposition, and the warping of film in order to produce a kind of fun house mirror effect. The achieved result is simultaneously psychedelic and formalist.

Diana Barrie

A student of Stan Brakhage (she often employed his hand-altered techniques) and important figure in the male-dominated underground, Diana Barrie’s clever, feminist reimaginings of mythical and religious narratives (My Version of the Fall) and boundary-pushing explorations of the female body (Night Movie) deserve a wider audience. Unfortunately, her films are hard to find online, but she is sometimes lauded at film festivals.

Aldo Tambellini

I implore you to see any and all Aldo Tambellini exhibits you can find. From James Cohan Gallery:

Iconoclastic and experimental artist Aldo Tambellini was among the first artists in the early 1960s to explore new technologies as an art medium. Tambellini combined slide projections, film, performance, and music into sensorial experiences that he aptly called “Electromedia.” Such work informed Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable and Woody and Steina Vasulka’s The Kitchen [a Chelsea neighborhood art space established in the ’70s]. With the rediscovery of this material, Tambellini’s work has become the subject of great interest for early new media.

Kroger Babb

The most prominent member of the 40 Thieves, a circle of innovative and money-minded American exploitation film distributors (the name was well earned), Kroger Babb bridged the gap between art-house and grindhouse. In addition to roadshowing sex-ed films from the ’30s, Babb recut and distributed the titillating scenes in Ingmar Bergman’s Summer With Monika (retitled: Monika, The Story of a Bad Girl) — which got him sued (although he got away with screening the film for five more years). Babb also played mentor to sexploitation king David F. Friedman, producer of seminal works in exploitation subgenres like “roughies” (The Defilers) and Nazisploitation (Ilsa She-Wolf of the SS).

Jud Yalkut

Just when you thought the polka-dotted creations of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama couldn’t be more psychedelic…

“One of the most influential filmmakers making experimental cinema in New York in the 1960s was Jud Yalkut,” writes film scholar Wheeler Winston Dixon. “Since then, Yalkut has gone on to consolidate an enviable reputation as one of the most important metamedia artists in American independent cinema.”

Joe Sarno

Known as the “Ingmar Bergman of pornographic films,” Joe Sarno is currently the subject of a retrospective at Anthology Film Archives that will wrap up in mere days (run, don’t walk). “The writer and director of literally dozens of low-budget erotic features targeted at the 1960s ‘adults only’ film market, Sarno is one of the true pioneers of celluloid erotica and one of sexploitation’s most sincere and critically-celebrated stylists,” writes Anthology. Films like 1974’s Confessions of a Young American Housewife feature the typical swinger-style sexcapades from sexploitation features of the period, but Sarno disarms audiences with a surprising intimacy and emotion as a conservative homemaker explores her newfound sexual freedom.

Nick Zedd

“If it’s not transgressive, it’s not underground. It has to be threatening the status quo by doing something surprising, not just imitating what’s been done before.” —Nick Zedd

It will all make sense after reading the Cinema of Transgression Manifesto . Watch some of the films from the movement on UbuWeb.

Pierre Clémenti

You’ll recognize Pierre Clémenti as Catherine Deneuve’s gangster lover in Luis Buñuel’s Belle de jour, but he collaborated with a number of visionary directors from the ‘60s and ‘70s (Pasolini, Bertolucci, Visconti). An 18-month prison term and drug charges tarnished his career, but he found acceptance in the French underground film movement and made a movie with Warhol Superstar Viva.

Shirley Clarke

A peer of indie icons Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, and Jonas Mekas, Shirley Clarke’s provocative works dismantle the celluloid facade with off-camera interjections from the director (see: her 1967 film about gay, African-American performer Jason Holliday, Portrait of Jason) and other voyeuristic techniques.

Naomi Levine

Jonas Mekas championed the work of Warhol superstar Naomi Levine (Kiss, Batman Dracula), who eventually broke out on her own as a director with a 1964 film called Yes. “Naomi Levine has just finished her first movie. It is like no other movie you ever saw. The rich sensuousness of her poetry floods the screen. Nobody has ever photographed flowers and children as Naomi did,” wrote Mekas. “No man would be able to get her poetry, her movements, her dreams. These are Naomi’s dreams, and they reveal to us beauty which we men were not able to rip out of ourselves — Naomi’s own beauty.” From an interview Mekas conducted with the filmmaker:

JM: Why did you make Yes?

NL: Because I wanted to make something beautiful.

JM: Why ‘something’ beautiful? Why not something perceptive — or of social consequence — or sexy?

NL: Beauty is all of these things. You see, I went to Puerto Rico and made a demonstration at Rami Air Force Base — and fifteen people lost their jobs and were beaten up and their homes wrecked. So I realized that this was not the way. The way would be to make something, to give something tot my world more beautiful and of life than these armaments which are merely ugly and full of pain.

JM: Do you think you succeeded?

NL: That is impossible — maybe here and there — maybe a glimmer, an instant of what I would like to give, of all I experienced. So that I now know where to work from and toward, as a whole. I know — after working with five versions and many editing revisions, etc. — the world of Movie, the world of People, is the way for me to go.

JM: How do you make your movies?

NL: Anything that happens on a set happens — there is no ‘acting,’ no method to get what goes on. It’s real and it has gone on for me forever. When I kiss I am kissed and I have kissed.

Sogo Ishii

The Japanese underground auteur, whose works like Burst City preceded the Japanese cyberpunk craze and have inspired Japanese filmmaking greats like Takashi Miike, was featured in our list “The 50 Weirdest Movies Ever Made.” “I’ve been making movies since I was 19 years old. My first film was shot on 8mm, it was called Panic in High School. At the time it was very difficult for young people to make films in Japan,” Ishii told Midnight Eye. “It still is, in fact. Most directors are over 40, and the normal process is to begin as an assistant director, then gradually move on to directing. I didn’t want to be an assistant director and I just started making films by myself. So yes, my way was different from the usual way.”

Photo by REX/Shutterstock

Lloyd Kaufman

All you need to know about the co-founder Troma Entertainment and director of The Toxic Avenger, Class of Nuke ‘Em High, and Terror Firmer can be found in his book, All I Need to Know about Filmmaking I Learned from the Toxic Avenger. The New York City filmmaker is also chatty on Twitter.

Robert Downey Sr.

From the man who brought us Robert Downey, Jr. comes cult classics such as Putney Swope (a scathing satire of the advertising industry) and underground parodies like 1966’s Chafed Elbows, starring the director’s former wife, Elsie Downey, in every female role. Downey captured most of the animated stills for the movie with a 35mm camera, the film of which he had processed at a drugstore. The elder Downey’s humor was avant-garde for his time, and even his bigger-budget projects, like Greaser’s Palace, an acid western with a Christlike pimp as the main character, bristled the mainstream.

Roger Corman

The King of the Bs. A legend. Half of Hollywood owes its career to Roger Corman (James Cameron, Jack Nicholson, and Martin Scorsese all got their start with him). Essential reading: How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime .

Radley Metzger

Adult cinema pioneer Radley Metzger injected an art-house aesthetic into his literary-inspired sexploitation productions:

Hoping to cash in on Europe’s sexploitation canon in 1960’s America, Metzger began importing and distributing erotica (The Fast Set, The Twilight Girls, I, a Woman), which led to his sexploitation directorial debut — 1965’s The Dirty Girls. Metzger’s take on the genre was slick, sexy, and glamorous — productions that felt closer to art films or high-fashion photo shoots than smut. The locations were exotic, the women seductive, and Metzger’s compositions striking—but the filmmaker never veered away from controversial subjects.

Photo by Marion Faller/Kobal/REX/Shutterstock

Hollis Frampton

Criterion’s 2012 Blu-ray release, A Hollis Frampton Odyssey, is a beautiful bible of the structuralist filmmaker’s work:

An icon of the American avant-garde, Hollis Frampton made rigorous, audacious, brainy, and downright thrilling films, leaving behind a body of work that remains unparalleled. In the 1960s, having already been a poet and a photographer, Frampton became fascinated with the possibilities of 16mm filmmaking. In such radically playful and visually and sonically arresting works as Surface Tension, Zorns Lemma, (nostalgia), Critical Mass, and the enormous, unfinished Magellan cycle (cut short by his death at age forty-eight), Frampton repurposes cinema itself, making it into something by turns literary, mathematical, sculptural, and simply beautiful—and always captivating.

Abel Ferrara

Ferrara straddles two worlds. At his grittiest and goriest, he found a cult audience in the downtown underground (Driller Killer, Ms. 45). But Ferrara is also one of the rare underground filmmakers to find acceptance with mainstream audiences and critics (Bad Lieutenant). Ferrara has refuted the underground label. “I’m a college-educated white boy. I eat at Morton’s with the other guys,” he told New York Magazine in 1993. Ms. 45 star Zoë Lund called him a “junkie-voyeur,” observing: “He likes to surround himself with people from the criminal element because he wants to get a peek behind the curtain, and he doesn’t want to pay for it.” That dichotomy lends a fascinating tension to his work, but has also stigmatized his career.

The Vienna Actionists

The transgressive, violent, and political films of the experimental Viennese Actionists make the most daring of directors look like pussycats. The films acted as a documentation of the movement’s performative works, but are singular works of art in their own right. An article in Issue 84 of Frieze explains the group’s trajectory and how these challenging artists (Kurt Kren, Otto Mühl, and company) are perceived in their home country today.

Jörg Buttgereit

Best known as “that guy who made those films about necrophilia,” maverick moviemaker Jörg Buttgereit’s experimental film career started in the 1970s with a series of satirical shorts. He became known for his radical avant-garde, nihilistic examinations of depravity and social consciousness (the Nekromantik series and Der Todesking).

Harry Everett Smith

New York City beat scenester, oddball collector, mystic, and former Hotel Chelsea resident Harry Everett Smith makes George Lucas look slightly less obsessed. His surreal animations, featuring hand-painted celluloid, made the editing rounds more times than Star Wars. Smith’s patchwork, improvisational approach to filmmaking resulted in wild experimentation. He was also a beautiful weirdo, as website Harry Smith PDX vouches for with this story: “He created elaborate customized equipment to project his last major film, Mahoganny, and then threw it out the window.”

Doris Wishman

“Nudie-cutie” filmmaker Doris Wishman infiltrated a guy’s club of sexploitation cinema in the 1960s with her titillating nudist camp “documentaries” and low-budget softcore pictures. Wishman’s work can hardly be described as feminist, but she was an astute businesswoman and prolific filmmaker who wrote, shot, edited, and produced her own work.

Curtis Harrington

The Harvard Film Archive on actor, director (he even gave us psycho-biddy classics like Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? and What’s the Matter with Helen?), film critic, and new queer cinema pioneer Curtis Harrington:

Marginalized by film historians and largely overlooked during his lifetime, the late Curtis Harrington (1928-2007) was a key figure in the West Coast experimental film scene and among the most wholly original directors to work in the Hollywood studio system. An ardent cinephile since his earliest years, Harrington began his film career as an errand boy at Paramount and eventually became a successful A-list director at Universal in the 1960s. An early protégé of Maya Deren and a close friend of Kenneth Anger and Gregory Markopoulos, Harrington’s first works were poetic trance films that revealed his careful eye and distinctive style. During his youth Harrington also befriended two of his greatest idols, iconoclastic studio directors James Whale and Joseph Von Sternberg, uncompromising aesthetes whose refined—and at times, perverse— tastes and wicked sense of humor would remain major influences on all of Harrington’s major films. This series pays tribute to an artist who never lost sight of his youthful ideals and produced a dazzling body of work ripe for rediscovery.

Kazuo Hara

Japanese documentary director Kazuo Hara’s films were confrontational in ways that presaged the obsessive docs of Errol Morris and Werner Herzog. His guerrilla-style filmmaking and exploration of forbidden subjects was revolutionary, intuitive, and provocative. In The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, he chronicled war crimes committed by Japanese soldiers in occupied New Guinea during World War II. The story is told through the impassioned investigation of a veteran who blamed the atrocities on Emperor Hirohito (a taboo accusation in Japanese society). His first feature, Goodbye CP (1972), is a challenging look at shunned Japanese men and women with cerebral palsy, while 1974’s Extreme Private Eros is a confessional, relentless documentary centered on Hara’s relationship with his feminist lover Takeda Miyuki.

José Rodriguez-Soltero

J. Hoberman on queer and Latino New York underground film icon José Rodriguez-Soltero, whose 1966 ode to Lupe Vélez, Lupe, is often neglected when mentioning the greats from the counterculture:

Rodriguez-Soltero was in his twenties, under the influence of Flaming Creatures and early Warhol, when he made these two exercises in super-saturated Kodachrome II thrift-shop glamour. Jerovi is a silent 10-minute study of a young dude who sheds his form-fitting brocade outfit—but not the red, red rose that he’s clutching—for some passionate al fresco onanism. This “sexual probe of the Narcissus myth,” per the filmmaker, was banned from the 1965 Ann Arbor Film Festival but wound up cited by Jonas Mekas as one the year’s best movies.

Thus encouraged, Rodriguez-Soltero embarked on a follow-up homage to Hollywood’s “Mexican Spitfire,” Lupe Vélez, whose suicide is graphically detailed in Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon. It was during the nine months that Lupe was in production that Rodriguez-Soltero staged his infamous LBJ at the Bridge Theater on St. Marks Place. Accompanied by the martial beat of America’s No. 1 song, “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” the filmmaker set fire to an American flag. (According to reporter Fred McDarrah, “The impact on the audience was sensational”: The event got a full-page spread in the next week’s Voice.)