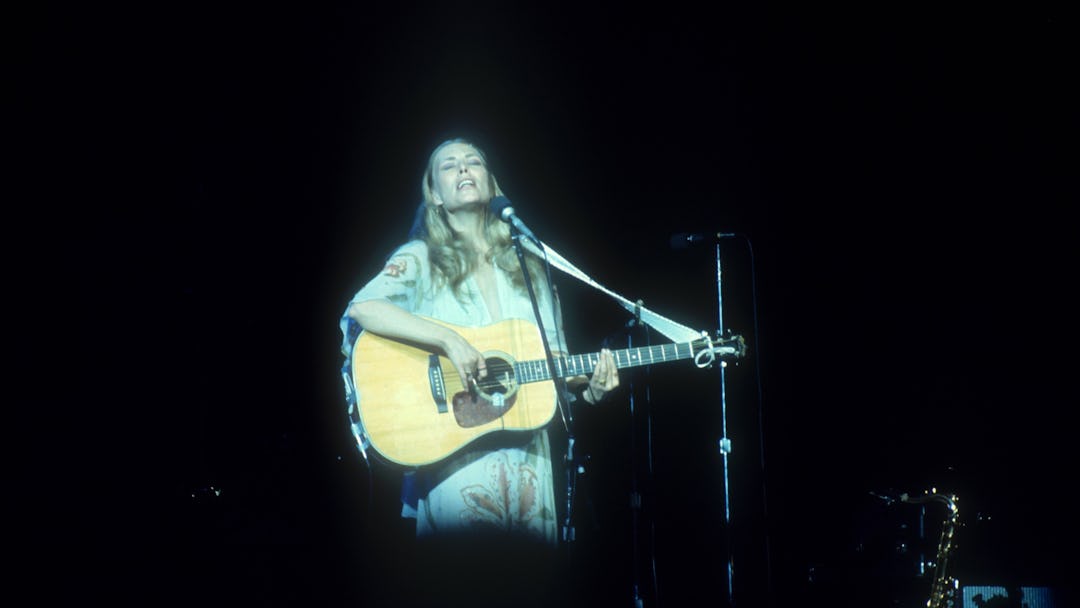

As befitting the star of Hedi Slimane’s spring campaign for Saint Laurent Paris, Joni Mitchell — singer, musician, and arguably the face of 1970s folk-rock and the “Laurel Canyon era” — is the face on the cover of New York Magazine’s new Spring Fashion Issue.

In a fascinating and disconcerting profile, we learn that Mitchell is the custodian of her own history, so much so that she was able to put the kibosh on a film adaptation of Sheila Weller’s Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon — and the Journey of a Generation: “I squelched that! I said to the producer, ‘All you’ve got is a girl with high cheekbones,'” she has said — referring, of course, to Taylor Swift. As befitting a canonical artist in the legacy stage of her career, Mitchell is also fiercely invested in making sure that various biographies are seen as “gossip,” and in curating her own artistic output. She carefully assembled her own recent 53-song, four-disc box set, Love Has Many Faces: A Quartet, a Ballet, Waiting to be Danced.

But what do Mitchell and the Laurel Canyon scene she was a part of mean to us these days? It’s certainly a buzzword — as recent profiles of Father John Misty prove, the Hollywood Hills’ Laurel Canyon neighborhood still stands strong in our collective memory as a place where a generation was able to create songs that stand the test of time. In the late ’60s and early ’70s, it became both a place on the map and a mecca — musicians like Frank Zappa, The Byrds, The Mamas and the Papas, Jackson Browne, Crosby, Stills, and Nash, and Mitchell all moved there and hung out together, sharing songs and beds and producing albums that have become classics. But are we remembering it as a post-hippie time of California experimentation, where there was an actual rock ‘n’ roll scene and everyone was creating good music, with Mitchell in particular at the height of her talents? Or has it become just a reason to dress in flowing peasant tops with no bra?

In a new Vanity Fair oral history of the Canyon, writer Lisa Robinson notes that we still hear its echoes in the music of today: “Four decades after those songs were recorded, their harmonies and guitar interplay have influenced such contemporary bands as Mumford and Sons, the Avett Brothers, Dawes, Haim, Wilco, the Jayhawks, and the Civil Wars. (Even the facial hair has made a comeback.)” The playfulness of the Laurel Canyon scene left its mark on rock ‘n’ roll, along with the idea that everything could be an inspiration — jazz, blues, psychedelia, and beyond.

Although that particular oral history comes with the caveat that “everybody was stoned,” Mitchell is decisively positioned as the fulcrum, as both a beautiful woman and the most talented person there. According to Stephen Stills, “David and Graham insist that they took me to Joni’s, which I knew was impossible because Joni Mitchell intimidated me too fuckin’ much to sing in front of her.” She was able to hang with the guys. “I was told that boys were able to be themselves around me,” she recalls. “Somehow I was, in my youth, trusted by men. And I was able to be a catalyst in bringing interesting men together.”

As Mitchell publicly wrestles with her image and legacy, with all the contradictions that she contains (she says that she suffers from Morgellon’s, a spooky and controversial, supposedly “all in your head” disease written about brilliantly by Leslie Jamison in a Harper’s essay called “The Devil’s Bait,” and talks about her “shared identification with black men”), it’s clear that she occupies a place in cultural history that few women get to achieve. She’s seen as a genius; she’s seen as difficult; she’s liable to produce an ornery pull-quote for an interview. She embodies contradictions that are often obscured in female artists. As Meghan Daum puts it in the essay “The Joni Mitchell Problem,” from recent book The Unspeakable, Mitchell suffers from “either being not liked or being liked for the wrong reasons.”

Joni Mitchell’s work already part of the canon. She has written songs that are full of small truths — especially about being female — songs that will last forever. But what she’s up to now is something different. It seems as if she’s trying to take her story back, to be in control of what has been a wild, fascinating life, from the ’60s to the present. Whether we’ll listen to what she has to say beyond the patina of Laurel Canyon cool remains in question — a question the New York Magazine piece leaves wide open. She’s never been a cut-and-dried, easy feminist icon, and as Daum argues, she’s misunderstood more often than not. Above all, Joni Mitchell is a woman who lives life on her own terms, from her artistic heights to her legacy years, and there’s something continually interesting and complicated about her. She’s a difficult woman. It’s a reason to admire her, but I’m never quite sure if it’s a reason to love her; and at the end of the day, I’m sure she doesn’t even need my love, anyway.