Tina Fey’s comedy has often been one of subversion. It’s never subtle: her punchlines themselves commonly land as the result of an abrupt undermining of stereotypes. Her shows’ jokes set up platforms for offensiveness, leading you to question whether she is (or perhaps more accurately, she, her co-creator, and team of writers are) perpetuating a culturally backward notion — then they turn. On 30 Rock, Kenneth Parcell is a “chinless” country bumpkin, but he’s actually immortal and mystically chinless and will eventually become a corporate CEO; Grizz and Dot Com — meant, as the brawn of Tracy Morgan’s entourage, to be paragons of black masculinity — just want to discuss their feelings; Tracy seems womanizing and adulterous but only upholds this image to hide his unmarketable loyalty towards his wife.

30 Rock didn’t always get it right — and at times could relapse into simply imitating and reifying the stereotyping it critiques. But the material was often commendably fresh, and, as the jokes sneakily hijacked themselves, viewers’ knee-jerk declarations of offensiveness actually would in turn read as its own form of stereotyping projection. It makes sense that Fey would be the person (along with her Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt co-creator, Robert Carlock) to finally write a “gay best friend” who echoes past manifestations of the stock character — in a now somewhat radical fashion — while also being much more than a “gay best friend.” Titus Andromedon, played by Tituss Burgess, is gay-best-friending in exactly the right moment, in exactly the right way.

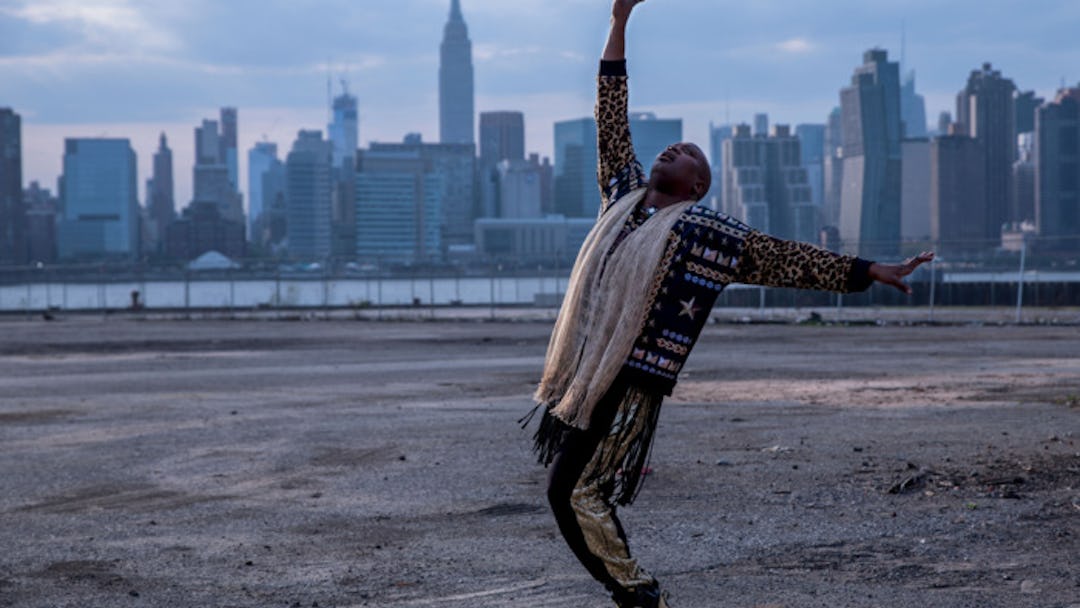

Titus Andromedon, as he — and just about everyone else — so often notes, is gay, femme, black, and bald. He’s also worried about aging. This series of qualities marginalize him, leading him to have difficulty in his ever-burgeoning musical theater career and also, at one point, to say, “I’m not even gonna know what box to check on the hate crime form.” They also lead him to be incredibly strong: he and Kimmy have met opposite, but similarly sculpting, forms of adversity — his has been societal and hers, as a former “mole-woman,” has been characterized by the utter lack of society.

And — unlike most characters we’ve seen on TV who match an amalgam of any of the aforementioned superficial descriptions of Titus — he’s one of the show’s two stars. He and Kimmy get almost equal screen time, each receiving their own independent subplots. While Kimmy and Titus’ companionship is central to the show, Kimmy has her own subplots with Jane Krakowski’s Jacqueline Voorhees and Titus has his with Jacqueline’s polar opposite: Carol Kane’s Lillian Kaushtupper. The opposition of the two characters’ narratives when they’re apart (Kimmy in a wealthy woman’s home, Titus scheming with the unglamorous, politically radical, dirt-poor, and brilliantly named Kaushtupper) suggests that, almost unprecedentedly, the GBF also has a Female Best Friend in Kimmy. She is his confidante and aid as much as he is hers — he has his own life as much as she has hers. Despite the show’s title, its structure staunchly asserts this.

To understand Titus’ cultural importance, we have to understand the GBF traditions in which he’s rooted, and which he’s subverting. It’s been a long road for gay best friends, which is part of the reason why they have — rightly, at least in the past — been singled out as an offensive trope. The “gay best friend” was film and television’s way of testing the waters of representing gay men at all. In gay best friends, the zeitgeist makers were saying, “We want to acknowledge these people exist. We even want to go so far as to make them seem… friendly.” Gay villainy had been a major cinematic trope long before gay people were given the luxury of getting to throw constructive shade at their girlfriends’ spaghetti straps. Villainy was funneled into the less offensive category of pure sass.

It goes without saying that gay best friends existed to comfort their female best friends, appearing only in their scenes, existing only within the confines of their girlfriends’ tumultuous (and singularly in need of some magical gaaaaay sartorial/relationship help) worlds; like domesticated dogs, they could cuddle when comfort was needed, they could bark when criticism was needed, and most importantly, they were neutered. They could also disappear when they’d done their jobs.

The gay best friend seemed to reach its peak in the late ’90s to early 2000s — when the polite, relatively asexual Will and Grace was the paragon of onscreen gay representation, and when Carrie had her Stanford Blatch and Charlotte had her Anthony Marentino. TV asserted a newfangled social liberalism with these equivocal accessories. And because the GBF was invoked to enliven a scene with their female friends, the criterion was often that they emulate them in their mannerisms. While gay romance and drama was mainstreamed with masculine-performing characters like the Brokeback boys, “femmy” men were relegated to more comic, supporting roles.

This trend, it seems, may have sparked or perhaps furthered a very unattractive trend in gay culture itself: femmephobia. As is not particularly uncommon, Looking actor Russell Tovey made a comment last week that seemed to hierarchize gay people according to levels of masculinity. (He has since apologized and said his words were taken out of context). Hollywood planted seeds that suggested that effeminacy was akin to gay irrelevance, to desexualization. After it was clear that the “gay best friend” had become a tokenizing trend, people started to turn against it, and it seems the impotency of the GBF trope has become conflated to some extent with the dismissal of femme men in Hollywood. Looking — TV’s one modern “gay experience” show — has predominantly forgotten effeminate men. Girls‘ Elijah is “femme” acting, but he’s also a complete sociopathic terror.

It’s assumed that actors like Tom Cruise or Will Smith or John Travolta — who have all been the subject of gay rumors for years — wouldn’t deign to come out due to the woe these stereotypes would inflict on their constructed hyper-masculinity (not to mention their Scientology). Being affiliated with the “femme” stereotype is one of the biggest fears for gay men who are still coming to terms with what “gayness” means to their ingrained masculine performances: if an air of masculinity is upheld, they can prove to less tolerant friends — and to the less tolerant sides of themselves — that their sexuality hasn’t changed them. We’ve come to a strange place with the GBF: a stereotype arose, the stereotype was identified and critiqued, and in attempting to quash it, a form of selective homophobia may have been bolstered.

The gay best friend, insomuch as he’s friendly and perhaps in touch with his feminine side, needed to return, subverting both the original stereotype and its backlash. Felix Dawkins on Orphan Black could fall into this category of radically sexual neo-GBF — but he’s dreadfully written, and thus far has functioned too much as Sarah Manning’s sidekick. But Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt wants to start a lot of things from scratch. This idea is embedded in the show’s very premise — of a “mole woman” released from the bunker where she’s been captive for the past 15 years as part of a sinisterly braid-sporting apocalypse cult.

The beauty of Kimmy’s experience is that, unlike the rest of us, she gets to see the world anew, despite its ills having continued and morphed while she was underground. The show acknowledges and assesses these ills — it brings in race and age and sexuality and feminism because it is firmly rooted in satire of America’s uglier sides — but it then allows itself, like the ever-smiling trauma survivor Kimmy, to start anew. For this reason, it’s not afraid of retreading a trope like the GBF, locating its origin — the obvious existence of femme gay men, and the obvious existence of friendships between gay men and women — and cutting the stereotypical crap. Titus, thankfully, is as sexual as any of the other characters on the originally made-for-NBC show. What would be particularly excellent, now that the sitcom has been moved to Netflix, would be to see Burgess truly get down with some other dudes.

This may come as a surprise, but the idea that gay men can be women’s best friends isn’t the problem. Despite years of worry about a certain negative cinema/TV trope, I still like to think that gay men can enjoy a healthy social life — and even, subversively, provide advice to a woman — without perpetuating an insidious stereotype. And I’d like to believe that the same could be said for TV characters. Kimmy Schmidt reminds us that this, alone, is not a stereotype, but just a relationship. And despite the show existing in an absurd alternate universe, it seems unprecedentedly real.