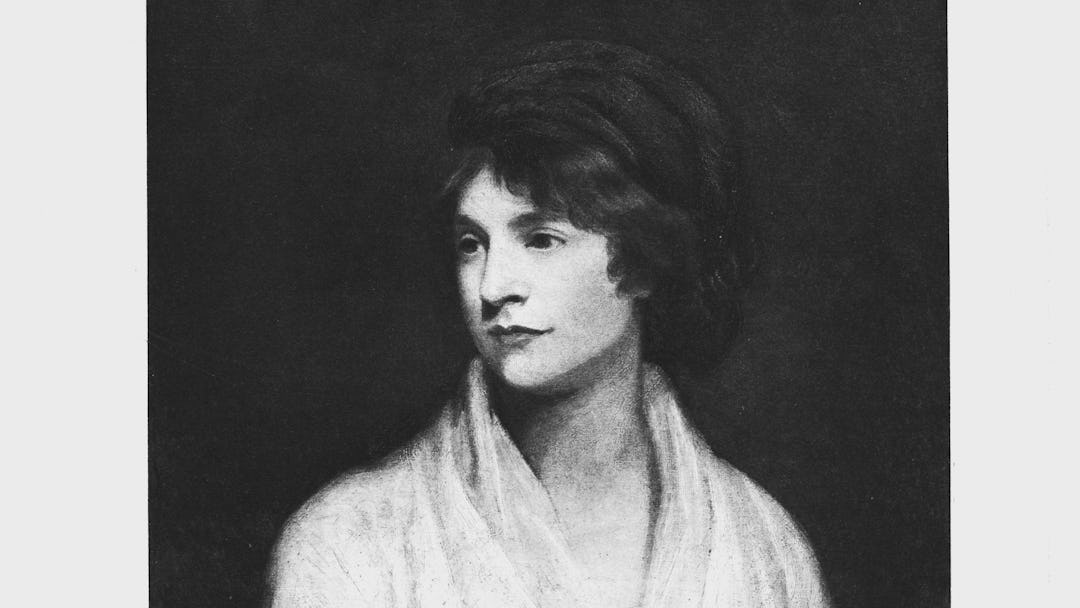

Mary Shelley was the brilliant parent of science fiction who hobnobbed with the Romantic poets and gave us Frankenstein, our most enduring monster-cum-morality tale, a woman whose wild and daring existence was whitewashed by her descendants. Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was a self-created political genius and writer of “A Vindication of the Rights of Women,” whose sexual lifestyle — radical for her time — meant her intellectual legacy was trashed for a century until her work was “exhumed” by female scholars who recognized her as their forbear.

Arriving on shelves today, Charlotte Gordon’s immense, and immensely readable Romantic Outlaws is the first-ever dual biography of the “Marys.” The political philosopher mother and the imaginative artist daughter both come alive on Gordon’s pages, which alternate, chapter by chapter, in between the women’s separate lives — thereby allowing us to see the parallels between them but to also feel, in a visceral way, what a loss it was that they didn’t get a chance to know each other. While young Mary Shelley (born Mary Godwin) never knew the mother who died days after childbirth, she was devoted to the ideal of the woman for her entire life. It’s hard not to think about the comfort they might have given each other in a world that was hostile to them both.

While feminist in outlook and serious in tone, Romantic Outlaws delivers its goods partly by offering delicious literary and historical gossip. Some of the best anecdotes in Romantic Outlaws involve other famous thinkers and poets, unavoidable since each woman wrote to, debated, and kept company with the brightest minds of her generation. Scenes include Samuel Taylor Coleridge reading “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” while young Mary Godwin (later Shelley) eavesdrops, American Vice President Aaron Burr calling Mary Godwin and her sisters “goddesses” and frolicking around the house with them; the elder Wollstonecraft walking through revolutionary Paris, stepping into a river of blood from the guillotine, and being encouraged to hush her gasp of consternation given the dangerous late-revolutionary climate. With bright masses of hair and “voluptuous” figures, both women boldly pursued and were pursued by men, often resulting in heartbreak. Byron, Keats, Leigh-Hunt and other Romantics flit in and out of Mary Shelley’s account, as do each of the Marys’ husbands; William Godwin and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Romantic Outlaws is a feminist project, in that it consciously valorizes both Wollstonecraft and Shelley while showing that they suffered at the hands of their husbands and fathers. As enlightened as their husbands were for the times they lived in, Gordon shows us how the “free love” and openness that both women espoused on a theoretical level injured them far more than it hurt their partners who had the freedom of movement they lacked. Their story makes it quite clear how perilous unorthodox sexual choices could be. Even if mother and daughter both thought marriage was an outdated tradition, each ultimately chose to make her bonds legal (and church-sanctioned) at some point in order to secure herself in an almost impossibly hostile climate for unmarried women who had known liaisons. Mary Shelley’s father (and Wollestonecraft’s widower) William Godwin, famous radical though he was (he’s a forefather of anarchism), had refused to talk to her for over two years until she stopped living in sin and wed Shelley.

And then after each of their deaths, their legacies were altered because of the constraints through which women were viewed. William Godwin wrote a memoir of Mary Wollstonecraft wherein he essentially outed her as a depressive and described her many love affairs. Regressive society flipped out, and her reputation suffered for decades (she was simply considered “a whore” by many). A generation later, Mary Shelley’s daughter-in-law Jane scrubbed both the importance of Frankenstein and the rocky, infidelity-strewn aspects of the relationship between Mary and poet Percy Shelley from the record, sanitizing her mother-in-law for respectable posterity. This led to the Frankenstein author being considered an intellectual lightweight whose accomplishments paled in comparison to her husbands. “They were attacks from opposite grounds,” writes Gordon of the efforts to sully both Marys’ reputations. “But both were equally and terrifyingly successful.”

Another feminist thread that runs through each woman’s story is how much extra they had to endure to be taken seriously as women thinkers in their time. Abuse and neglect from parents and step-parents as well as lack of education didn’t stop them from publishing their writing, much of which ended up being savaged by critics. “There was too great an emotional cost in writing a book and then watching as people abused it,” writes Gordon of Mary Shelley. Finally, she tries to reconcile Shelley’s seemingly apolitical output with her mother’s legacy by explaining that their feminism was a common tie:

[Mary Shelley] was far more suspicious of the legislative process than her mother, father, or husband, having seen how little was gained by their public stands and how much was lost. But that didn’t mean she wanted to distance herself from her mother’s radicalism. For Mary, change could come about only through art, through the actions of individuals and the integrity of one’s relationships… In all of her work, she emphasized the importance of the independence and education of women and critiqued the traditionally male values of conquest and self-promotion.

The struggles both Shelley and Wollstonecraft endured on their way to being independent thinkers and writers, and their efforts to reconcile their romantic passions with the misogynist strictures of their time, are relevant to so many conversations still going on today about art, activism, and how women can carve out intellectual space. Gordon’s work may not break a huge amount of new historical ground, but her project goes well with the current feminist zeitgeist: placing these two writers in the historical pantheon beside the men they kept company with in life.