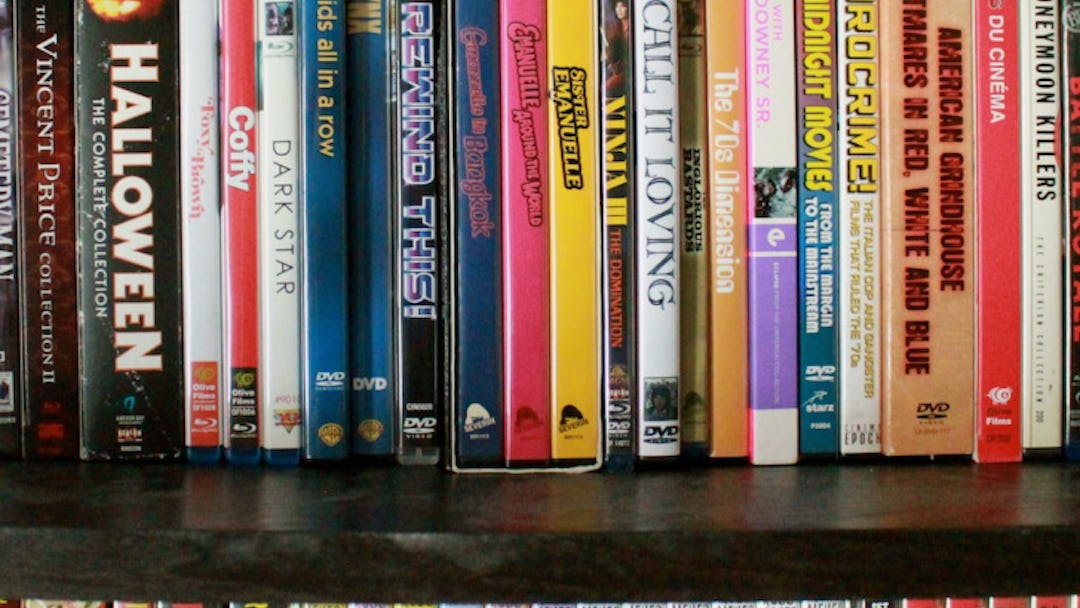

Matt Desiderio isn’t sure how he feels about me taking photos of his movie collection. It’s not that he isn’t proud of it — quite the contrary. Falling off the shelves in his living room, carrying over into not only his bedroom, but also a spare second bedroom that he’s dubbed “the video room” (accurate, since you can barely fit another person in there), it would be the envy of any self-respecting cult movie buff. It’s a question of presentation; he recently had to move, after a plumbing failure in his last apartment, and while the movies are unpacked, he’s not entirely happy with how he’s got them displayed. It’s not quite right yet.

He’s got a lot to work with. Since he started collecting movies at age 17 (he’s 33 now), he’s literally lost count of how many VHS tapes he owns. “I stopped counting around 5000,” he says. “I probably stopped caring about how many I had when I got to that point.” (He threw out “at least a thousand” tapes in the move, due not to water damage but just an overdue purging; “You know, how many video fireplaces do I need?”) He’s got DVDs galore, and quite a few Blu-rays as well — even though he doesn’t have a Blu-ray player yet. “I know I’m going to want to watch them eventually,” he says, shrugging.

What he doesn’t have is a Netflix membership, or even a computer. There’s a laptop on the coffee table in his crowded living room, but it’s his girlfriend’s, he explains; he’s not against watching a movie on Netflix or Hulu, though he often does it just to scope out films he might want to buy. And if he does, it’ll go on the shelf, organized by title, or genre, or (in the showplace area, the living room) by distributor — lumping together, say, the Elvira ThrillerVideo titles, or the Warner Brothers clamshells, or whatever oddball label put out Ray Dennis Steckler’s Rat Fink and Boo-Boo (Matt has two copies).

It’s impressive; I thought I had a pretty respectable collection until I saw this one. I spend a lot of time complimenting the eclecticism on the shelves, asking about noteworthy titles, recognizing specific tapes that take me back to my video store days. At the end of the interview, I ask again about a photo, and he’s OK with it. We pick the best corner, and he grabs a collector’s replica of the title creature from Critters off one of the other shelves. He asks if I mind if he poses with the Critter. I don’t. We take the picture.

* * *

Matt isn’t just a funny guy or an enthusiastic movie buff; increasingly, he’s the kind of movie fan that home video distributors are dependent on. Casual buyers might not have noticed, but sometime in the middle of the last decade, people stopped buying movies on disc. Not everyone, of course — DVD and Blu-ray remains a lucrative source of ancillary revenue — but after nearly a decade of double-digit year-to-year growth, DVD sales flatlined in 2005 and 2006, and fell for the first time in 2007. The causes of that fall (which has continued over every subsequent year, and is expected to extend through this decade) were multifold: the recession, the uncertainty caused by the “format war” of Blu-ray vs. HD-DVD, consumer reluctance to keep buying DVDs in the face of those superior formats, general distaste for the notion of buying all their movies over again a mere decade after DVD supplanted VHS.

And then there was Netflix, which launched its video streaming service in 2007 as a supplement to its DVD-by-mail business, only to see the former take over the business so quickly that, by 2011, the company (unsuccessfully) attempted to sever the physical media arm of the service. By that time, thanks to the convenience and low price of both their DVD mailing and Instant Viewing services, Netflix had all but decimated the disc rental market; Blockbuster Video had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2010, having itself put the bulk of independent video retailers and competing chains out of business years earlier.

Now, home viewers watch movies via Netflix and other streaming and download services like Amazon Instant Video, Hulu, and iTunes. But with each new iteration of the home viewing experience, the volume of available titles decreases. All of the movies available on celluloid never made it to VHS. All of the movies available on VHS never made it to DVD (40-45% never crossed over, according to estimates). And not all of the movies available on DVD are streaming — it’s not even close.

Not everyone wants to trade variety for convenience. “I am not excited about streaming at all,” says Quentin Tarantino, in Tom Roston’s new oral history of the era, I Lost It at the Video Store . “I like something hard and tangible in my hand. And I can’t watch a movie on a laptop. I don’t use Netflix at all.” Tarantino appears to be in the minority. Yet in the face of the overwhelming trends and depressing statistics, a handful of home video distributors are still fighting the good fight – serving that underserved minority by hanging on to a seemingly outdated medium. They do it for the love of film, but they’re also making a few bucks in the process.

* * *

To be clear, plenty of consumers hoping to rent or buy new releases on DVD or Blu-ray are still taken care of. They’ve still got their little corner at Wal-Mart and Best Buy, and rentals are available at a few straggler stores and chains, as well as Redbox kiosks, which (44,000 strong in 36,000 locations) now account for half the DVD rental market.

It’s the catalogue market that’s the problem — older titles, which represented money lying on the ground during DVD’s early-‘00s gold rush. Once they go out of print, they join the films that were never printed, languishing in studio vaults or available only via bare-bones, burn-on-demand outlets like Warner Archive.

The leader of this market remains the Criterion Collection, which launched in 1984 as a LaserDisc label, presenting established classics and important contemporary films with painstaking restorations and copious bonus features like audio commentaries, interviews, and featurettes. They moved to DVD in 1998 and Blu-ray in 2008, and are considered the gold standard for cinephiles. Other labels like Olive Films and Kino-Lorber Studio Classics go lighter on the supplements, but are nonetheless making strides to get languishing studio titles back on DVD and upgraded to Blu-ray.

One of the savvier labels in the game is Shout Factory, initially founded (by three alums of the nostalgia music label Rhino Records) to focus on both vintage music and retro and cult TV. Over the years, the company has evolved to concentrate on video almost exclusively, releasing a steady stream of movie and television classics (alongside some new films), and figuring out a formula that works, even in the current climate.

“If your business is all about physical media, you’re going to be in trouble,” grants Jordan Fields, Shout’s VP of DVD & Acquisitions. “But we have seen great success selling DVDs and Blu-rays over the last years, even despite the downturn in the market — primarily because we’re serving a fanbase that wants physical product, either because its an older demo that isn’t as versed in digital consumption as others, or because there’s a collector mentality that simply needs to own it, and not only needs to own one product, but the definitive product.”

In other words, these days the key to staying in business as a physical media distributor is knowing your audience — one of cult fans and collectors, who are looking to own titles that go beyond not only the new release shelves, but also the IMDb Top 250. “You know it’s always going to be possible to explore the established canon, the essential titles that turn up perennial on every list,” explains Josh Johnson, who directed the wonderful documentary valentine to VHS, Rewind This! “But if you look more deeply, and try to develop a more holistic view of film history that takes up things that weren’t necessarily the most popular films of their time and try to establish a canon for yourself, it’s going to become increasingly difficult to do that, when the amount of material is less and less available.”

Still image from “Rewind This!”

And that’s where the specialty labels come in. David Gregory (no relation to the TV personality) co-founded Severin Films in 2006 with a firm focus on cult titles, particularly in the horror genre; their recent releases include the Italian giallo film Nightmare Castle, Jess Franco’s notorious Vampyros Lesbos, and the forgotten 1981 slasher film Bloody Birthday. And Gregory says, comparatively speaking, business is booming.

“It’s actually gone up a bit in the last year or so,” he says, “in terms of people buying these specialist, special editions of cult movies on Blu-Ray and also on DVD. So it looks like there are still bits of life in us doing these kinds of bells-and-whistles editions of movies — and even the really basic editions of smaller movies. It seems like the cult movie fans are interested in having a physical copy for their libraries.” Gregory may be on to something; with all the talk of physical media biting the dust, there’s almost a feeling, among collectors, of going to the store for loaves of bread and batteries before a hurricane. If rental options are going to be this limited, they want to bulk up their libraries while they can.

Joe Rubin, co-founder of the Vinegar Syndrome label, wasn’t even planning on getting into video distribution. He and his partner’s initial business was not a home video label but a film processing lab; “we weren’t anticipating the home video side becoming anything more than a hobby or an occasional vanity thing,” he says. But the response to their initial Kickstarter push and their earliest releases — which are almost entirely in the realm of vintage erotica, softcore and hardcore films from porn’s shot-on-film “golden age” — was overwhelming enough to change their original business model of a lab that also does preservations. “We honestly weren’t expecting the home video aspects to carry the business, as they currently are.”

Louis Justin’s Massacre Video was even more of a lark, a venture he started, he jokes, as “a way to not go to college, honestly.” His is a one-man operation focused on obscure horror and sexploitation movies, and that DIY approach has kept Massacre afloat while other companies have spent big on overhead and rights to bigger movies. “I deal with more niche, small titles,” he says, “so it’s easier for me to make a profit,” though the 25-year-old exec stresses, “I’m not living luxuriously at all.” But it’s worth it, he says, to get movies into the world the way he likes them: “I’ve never been a fan of streaming, never been a fan of any of that. I like to go to a video store, rent something, and come home with it.”

And you’ve gotta give Justin this: he puts his money where his mouth is, distributing titles not only on DVD, but — and you may want to sit down for this — also on VHS. “I’m a VHS collector,” he explains, “so when we got the very first release, we decided I was going to do a 50-copy VHS run of [the 1988 shot-on-video horror movie] 555, and I didn’t think it would sell at all.”

And? “It actually sold out in three minutes.”

* * *

An anecdote like that pinpoints the key factor in the survival of labels like these: the psychology of the collector. “I am an owner,” Superbad director Greg Mottola says in I Lost It at the Video Store. “Every movie that is really important to me, I either own it on VHS or DVD or LaserDisc. I like to reference that stuff.” At 51, Mottola is part of what Rewind This! director Johnson dubs “a particular generation that either grew up during the video boom or was alive for the period of time before it began,” for whom

the concept of owning a film is associated with having an object in your home. That was the key difference between a film that you had seen and a film that you owned and had constant access to. So there’s this emotional attachment to the object itself, because it represents your ownership of this thing that you love. I think the younger generation right now, because they are developing at a time when streaming has become the norm and accessing digitally has become the most convenient way to do it, I don’t know if they do have the same attachment to the physical object. I think for them a collection can be something that exists purely on a cloud or a hard drive.

Matt Desiderio sees these transactions from both sides. He’s not only a collector; he also stocks the sell-through titles at the New York comics and collectibles mecca Forbidden Planet. “People like presentation, people like stuff that looks cool; something cool is going to sell,” he says. “I think packaging and special features are really what makes people buy stuff nowadays, unless it’s that movie that you’re going to have to see. That’s the thing – why do I still sell copies of Sleepaway Camp? It’s because it’s packaged nicely, it’s got special features or whatever [else] they have, that they’re adding on to make people buy this. And [the distributors] make them look cool.”

Box art for Arrow Video’s release of “Alien Contamination”

If anything, he sees labels increasingly relying on “double-dips” (or even triple-dips), repackaging popular cult movies that are already available, but with a sprinkling of new special features or new art — cult distributors betting on a sure thing. “I got Alien Contamination,” he confesses. “I can’t tell you how many copies of Alien Contamination I have right now, but I still got [the new one], because it’s so cool.”

“There’s just something about having the actual item in your hand and having something on a shelf that’s, I guess, more of an intimate experience,” Massacre’s Justin surmises. And that’s what separates the consumers who patronize these companies. “I think the majority of our regular customers are the types of people who like to have a giant shelf of DVDs or Blu-Rays,” Vinegar Syndrome’s Rubin says, “and they organize their films by the director or the company that produces them.”

But the mindset Rubin sees most in his customers isn’t just about shelf organization or tactile pleasures. The people who buy the discs these labels put out, “whether it’s an obscure German Expressionist film or an obscure ‘70s X-rated film,” are people who “tend to be very film-literate. I think the idea of being literate in whatever the field is, whether it’s music, whether it’s books, whether it’s movies or any other thing, it’s the idea of ownership. People who are really into music tend to have very large record or CD collections. People who are into reading tend to have large libraries. The same thing is true with people who are cinephiles.”

And film history, at least for those with an interest in classics beyond Citizen Kane and Casablanca, is what’s being impacted by the convenience and low price tag of Netflix, Amazon Prime Instant Video, and the like. As director David O. Russell told Roston, “There’s a lot of stuff going on with the licensing and the deals where [streaming services] no longer have certain movies. It used to be that Amazon had everything, but Amazon changed their deal. And I’ll say it to the guy I know who owns Netflix: it’s a bunch of dreck.”

Wherever you sit on the ratio of dreck to quality in Netflix’s streaming library (or their willingness to let huge chunks of it go, in favor of producing their own new movies and shows), there’s no denying that it’s a selection that has less to do with film history or even film quality than with which deals the company has with which studios, and which B- and C-titles come bundled with the good ones. (Contacted for comment, a Netflix representative would not answer specific questions about how the service’s streaming and physical libraries are curated, explaining, “While we don’t discuss the particulars of our licensing agreements, Netflix does focus on licensing the movies and TV series that we think our members will enjoy, and we make licensing decisions based on a variety of factors.”) A 2013 op-ed by The Dissolve’s Matt Singer worried that the limited selection of classic titles on Netflix was creating a decidedly skewed “Netflix film canon,” and the numbers are indeed discouraging; at the time of his writing, a mere 17 of the AFI’s top 100 movies of all time (none of them in the top ten) are available for streaming on Netflix.

Netflix’s streaming choices for Woody Allen

Even worse, as Netflix’s business model has shifted from disc to online delivery — to, it must be noted, great financial success — discs have grown increasingly scarce, seemingly discarded after wear and tear render them unplayable, but not replaced. In spite of assurances that “there is still a huge demand there,” their disc library has troubling gaps. If you’re unsatisfied with their streaming selection of, say, films directed by Woody Allen (exactly three out of his 47 titles), you’ll still hit a wall on the physical side; 19 of those pictures (including Stardust Memories, Bananas, Take the Money and Run, Bullets Over Broadway, and Deconstructing Harry) aren’t available for rental by mail either. You can’t rent The Third Man or The Lady from Shanghai or Gentlemen Prefer Blondes or The Quiet Man or Modern Times or Grand Illusion or The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek either — none are streaming, and instead of the disc option, Netflix merely offers the ennui-inducing, no-promises “Save” button. That leaves the curious viewer to splurge on a rental or purchase download from Amazon or iTunes, if they’re lucky; if not, that means a blind buy, and that’s presuming the movie’s still in print.

And the loss goes deeper than access. As Johnson points out, “When you talk about people who continue to be passionate about physical media, they continue to be passionate about owning film as an object, but also exploring film as an art. Which means they’re interested in a lot of the supplemental material and the bonus content that is often not packaged with the official downloads. So they want not only something from the shelf, but they want something that’s going to expand their existing knowledge of a particular film. The average consumer is spending their money on films that they’re interested in seeing, whereas the collector is spending money on films they have already seen, know they love, and want to dive deeper into and continue to explore over time.”

* * *

It’s easy to become a gloomy Gus about the shifting winds, and to overreact as well. After all, the same kinds of obscurities these labels are keeping in the public sphere can benefit from digital exposure, to a rapt audience. “The blogs are never going to be a video store replacement,” director Joe Swanberg grants in I Lost It At the Video Store. “But a Fandor or equivalent website can be like that well-cultivated college-town video store, where you can’t find an Adam Sandler movie but you can find every Werner Herzog film. That kind of curation. Fandor’s whole vibe is not that they are going to have every movie that’s available. They’re going to have 30 movies that are going to be available to you now, and all of them are going to be good.”

And for name directors — marketable quantities — like Herzog, the access available to burgeoning film fans via digital downloads and streaming is immense. As director Alex Ross Perry notes in the same volume, “I’m sure that if I were 15 now, my viewing habits would be different. If I’m 15 in 2014, I’d probably have a hard drive with 20,000 titles, because if I want to get into Cronenberg, 45 minutes later, I have 27 movies to watch.”

So while these labels are continuing to serve their specific market, they’re also well aware of which way the wind’s blowing. “We’re certainly exploring a lot more digital options than we have in the past, because that’s really where the industry is going,” Severin’s Gregory admits. “And luckily it’s giving us a bit more time to perfect that, because people are still buying the physical versions of these films.”

He’s not alone; Shout Factory recently began an ambitiously programmed streaming channel of its own, Shout Factory TV, while Vinegar Syndrome just launched their streaming service Exploitation.tv. “With that said, the people who want physical media are very, very obsessive over it,” Rubin says. “We’re launching a streaming service and we’ve gotten so many worried messages, essentially saying, ‘This doesn’t mean you’re going to stop releasing DVDs, are you?’”

They aren’t — and it should be noted that while physical media sales have certainly fallen, it’s still a lucrative industry. As Home Media Magazine’s Thomas K. Arnold wrote last year, predictions have it that “consumers will still be shelling out a respectable $10 billion or so on Blu-ray Discs and DVDs in 2015 — half what it was a decade ago, but hardly an amount to be dismissed.” A new Nielsen study found physical media spending still tops digital ($2 billion vs. $873 million in 2015’s second quarter), with only 12% of respondents shifting entirely to “digital viewing methods.” Over half consume both physical and digital media; 20% still exclusively go with physical media rentals and purchases. There’s certainly the possibility that the death of physical media has become a self-fulfilling prophecy, a fear that’s become reality. But none of the experts I talked to think physical media is dead, even if their thoughts vary on how much life it has left.

“It’s definitely going to plateau at some point — we can’t expect a steady increase exponentially,” Rubin says. “But it’s a market that I don’t think will die, simply because the people who are buying these sorts of movies still want them as physical devices. And granted, our average age range is 35 to 45 and the people in that age range are certainly computer-literate, and though I’m sure a lot of them do download things and do stream things, there’s still a security in having the real thing, which is a physical copy.”

“I think DVD and Blu-ray are going to be just fine for a while, I really do,” Shout Factory’s Field says, noting that as it stands now, there are two types of releases: budget titles (“you’ll see a whole season for five dollars at Wal-Mart”) and “going in the other direction, which is the direction we tend to take, higher-end deluxe editions, targeting the collector…. The price is higher and margins are a little better and we don’t have to sell as many units.”

“I think the collectors’ market will keep it alive at least for the next couple of years, and possibly indefinitely,” Johnson says. “But I don’t think we’re going to see the tide turn and the general public move back towards wanting to own all of these physical objects [that] take up space in their house. I think the average person is content with easy access and minimal clutter. The collectors’ market, where people are passionate about owning this and delving further into cinema history, I think there will be a market there that’s large enough to sustain these small companies. I think, for the majors, they’re going to be producing less and less.”

“I’m hoping it’ll stay at this level for as long as possible,” Gregory says, “but the reality is, we have to accept it’s not going to last forever. There will always be people who want the physical media copy. But will it be enough to justify the work and the effort and the money we put into these films? I don’t know.”

For his part, as the kind of guy who’s doing the buying, Desiderio isn’t worried. “I don’t think that there is going to be a death of physical media,” he says. “There are going to be less stores, that’s the thing.” And while the loss of stores (and the sense of community among film lovers they engender) is worth mourning, there is an upside: with fewer middle men, more money makes its way back to the filmmakers, and to the distributors who take a chance on the smaller, riskier titles collectors seek out.

“I don’t see it stopping and everything going digital or VOD or whatever,” Desiderio says. “I mean, it’s possible maybe, way down the line; I’m only 33 and I’m like one of the last generations holding out on this type of stuff, so I kind of get it. Maybe eventually the masses will win and they’ll cut out physical media, but that’s way down the line, when people like me are dead. And as long as people like me are out there pushing it and getting it out there to younger people, maybe we have a fight.”