All Rocky Horror Picture Show fans, like everyone else who’s partial to a particular vice, can tell you the story of the transcendent experience that got them hooked.

For me, it was a screening at Los Angeles’ Nuart Theatre in August of 2000, just before my 16th birthday. I’d arrived in the city that day from the East Coast to visit a friend, and had already fallen asleep at one movie screening, as some combination of restlessness, air travel, and the time difference had kept me awake for over 24 hours.

But I couldn’t have nodded off even if I’d wanted to in the line outside the Nuart, surrounded by goths, drag queens, and other avatars of dark DIY glamour, jacked up on platform heels, dripping vinyl and fishnet and sequins. (I can’t remember dressing up for the screening myself, though at that age I was pretty much always in costume whether I realized it or not.) At 16, I had not found my people yet – not more than a few of my people, at least – but here it seemed possible I had located several hundred of them.

Inside, my friend and I sat at the dead center of the theater, intoxicated by the energy in the room and transfixed in that jittery way that’s inevitable when you’re dividing your attention between two competing spectacles – because in this case, as well as the B-movie on the big screen, there were actors staging their own simultaneous performance of it on the stage below. This live version was even pulpier than the film: stranded, white-bread couple Brad and Janet somehow managed to appear more haplessly innocent than they did on screen, and their corrupter, self-proclaimed “sweet transvestite” Dr. Frank-N-Furter, more flamboyant in his libertinism. Though I had watched Rocky Horror before, this was my first midnight screening with a “shadow cast” and audience participation, the only kind of viewing experience that counts for its most active contingent of fans.

The performance ended perfectly, with the stately, corseted man mouthing Tim Curry’s lines as a flesh-and-blood Frank-N-Furter crawling over the seats as he urged us, “Don’t dream it, be it.” I would like to say that I responded just as perfectly when he landed in my lap; I did not. I lifted my hands and then dropped them again, confused about whether or not I could touch him. (I absolutely could have. I mean, of course I could have.) Perhaps I deserved the moment of embarrassment for being too afraid to publicly surrender my Rocky Horror “virginity” during the pre-show. It was the only way I was going to learn that public humiliation before a proudly shameless audience was part of the fun. And it really was fun. When I finally went to bed early that morning, it was as a true believer.

Despite my conversion, I never quite became a part of what you might call the Rocky Horror community – partially because I wasn’t an actor, partially because my access to screenings was limited, and partially because I had too many other interests (and fell in love with too many other midnight movies) to devote so much time to just one. But for many years, I attended the occasional showing in a major city or a college black box theater, cobbling together my own costumes and dressing up my male friends like big, gothic baby dolls.

At the time, I believed Rocky Horror felt like home to me because I was a freak craving the company of other freaks. (Later, I might have acknowledged that it was also a good excuse to apply too much eyeliner while drunk.) But by now, almost half my life since that night in LA, I’ve drifted through enough subcultures to figure out that words like “freak” are so vague as to be useless. It wasn’t just the outsider camaraderie I liked. What must have truly captivated me was the attractive worldview embedded in this exuberantly bad, comically decadent, painfully low-budget – but somehow perennially watchable – movie and the four decades’ worth of traditions its fans have built around it.

When people discuss the message of Richard O’Brien’s musical-turned-film, it’s usually to point out either its empowering vision of self-creation (“Don’t dream it, be it” is indeed its key line) or its lightheartedly queer agenda. And in the broadest sense, that does cover its appeal. But at the risk of getting too serious about analyzing a film whose greatest asset is its sense of fun, Rocky Horror’s particular queer – and, notably, genderqueer – agenda is worth a closer look. This isn’t a movie where characters discover they’re gay and come out to their families; it’s a movie that (subtly, if anything about Rocky Horror can be called subtle) reveals how slippery the boundaries of what we call “identity” are, how confusing and situational and prone to the irrational whims of pleasure. Frank-N-Furter’s gender is so mutable and non-binary that his sexual encounters with Brad and Janet both have their queer elements.

This tracks with the way I was starting to see the world when Rocky Horror became a part of my life, midway through high school. Several years before the same-sex marriage movement reached critical mass, at a time when the mere mention of the campus gay-straight alliance could double as a punchline, there was a popular girl in the class above me whose boyish demeanor and style of dress seemed to normalize her relationship with another girl for the school at large. I had a female friend who was polyamorous, juggling multiple boyfriends and girlfriends, and inflecting our circle’s conversations with the vocabulary of BDSM. A gay male friend returned from a year abroad with a story about how he had almost married a woman. My own journals from that period contain plenty of harrumphing about “labels,” scattered amid more pervasive lamentations about why my interactions with boys resulted in weird power struggles more often than anything you could call a relationship.

Endless identity markers did not seem like they would make any of this easier to navigate. The only thing that would help was some loosening of the unspoken boundaries that were constricting the way we conceived of ourselves and guiding our behavior. Movies and books and songs that betrayed any understanding of this — that could make you feel like less of a freak for seeing the world this way — were few and far between. (Remember the way some women clung to Jill Sobule’s “I Kissed a Girl” or Ani DiFranco’s “In or Out” in the ‘90s? Well, try revisiting them now. Their earnestness seems quaint two decades later, but they served a purpose.) I ended up finding these ideas articulated in the pop culture of the early 1970s – all of which was available for consumption on Napster and in record or video stores. But none of it still existed as a real, live subculture — except for Rocky Horror. That it had endured for 25 years felt like a miracle.

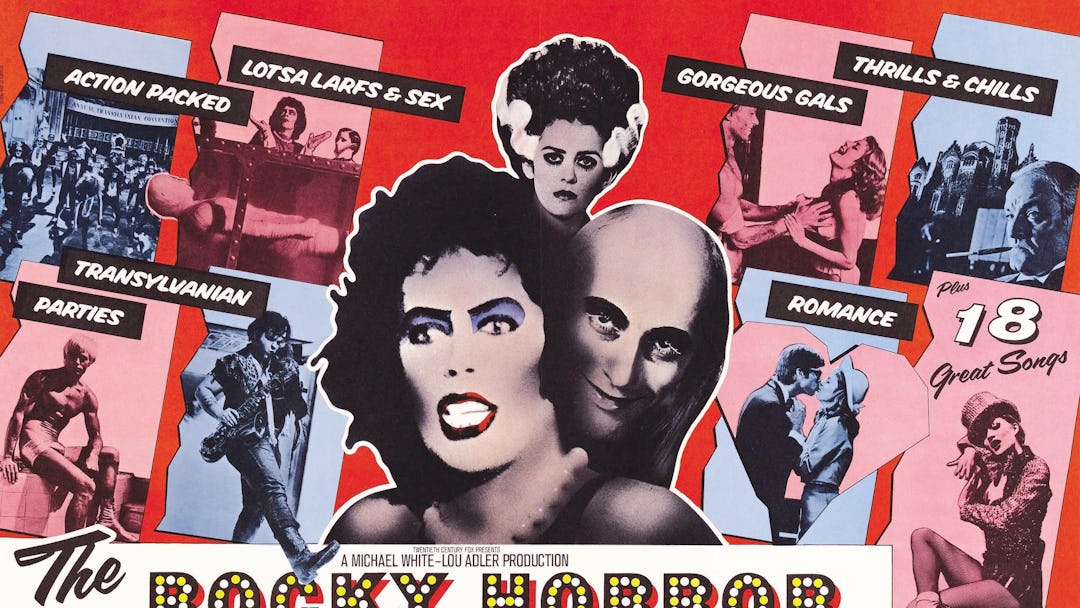

September 25 marks the 40th anniversary of Rocky Horror, and the film’s cultural presence is as strong as ever. This weekend will bring the release of a new photo book, People Like Us: The Cult of the Rocky Horror Picture Show, documenting cast members from around the country, and – at an anniversary convention in New York – the debut screening of a documentary titled Rocky Horror Saved My Life. But as the very existence these archival projects suggest, a hint of nostalgia seems to have crept into a milieu that has for decades split the difference between the past, the present, and a sort of nonspecific post-gender, sci-fi future.

Maybe that’s because, in many ways, Rocky Horror’s futuristic vision is finally becoming reality. Unfortunately, that’s not to say that the world is now a safe place for sexual and gender outlaws of all stripes – queer, trans, and non-binary people, especially those whose class and/or race puts them at further disadvantage, still face systemic oppression and horrific violence. But legally and culturally, this decade has brought the greatest society-wide evolution on issues of sexuality and gender since the ‘70s. From same-sex marriage to Emmy-winning TV shows about the real, non-tragic lives of trans people, kids growing up now can find plenty of affirmations – or just representations – of identities outside the hetero, cisgender norm without having to look too hard.

That includes identities that can’t be neatly categorized. An article in the current issue of New York magazine, for example, illuminates the struggles of women whose husbands began living as women after their marriage:

The experience can be especially challenging for straight women. For lesbians with transitioning partners, their place in the LGBT community can be somewhat preserved. But a woman whose relationship was ostensibly heterosexual must face questions related to her own identity. Milena Wood, who met her trans wife, Shannon, when they were both in the military, says she doesn’t necessarily mind being mistaken for half of a lesbian couple now that Shannon’s transition is under way, but she still doesn’t think of herself as gay, which makes it hard to know where to fit in.

And for the generation that’s currently coming of age, this type of confusion might not even seem worth parsing. When you consider that fewer than half of British people ages 18-24 identify as exclusively heterosexual and well over half disagree with the idea that sexuality is a fixed thing, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that we’re all on a voyage to the distant galaxy of Transylvania. So you can imagine a 16-year-old in 2015 watching Rocky Horror for the first time and not finding anything radical in it at all.

This possibility seemed especially likely after a midnight screening in Manhattan last weekend, my first in almost a decade. I had come in already resigned to the knowledge that I’d never recapture the Rocky Horror experiences I’d had as a teenager – and that wasn’t going to be anyone’s fault but time’s. But even a cast as talented and well rehearsed as New York’s couldn’t hide the extent to which the crowd differed from the one I remembered; it was all, seemingly, curious tourists and timid university students. If they had dressed up at all, it was in a wig or costume that might as well have still had a price tag attached. No one except the cast members seemed to know the callback lines, and no one seemed to be there because they needed to be there. The atmosphere wasn’t so different from what happens when a straight bachelorette party takes over a drag bar.

Lauren Everett, the photographer behind People Like Us, suggests that my experience in New York might not have been representative. “In the suburbs or other places where Rocky really is a cultural oasis (vs. big cities), there is often an extended social circle of regulars to come to a lot of the shows,” she tells me via email. “That happens in LA or other big cities too, but I think when the show is in a location where maybe it’s one of the only activities for people who feel like they don’t fit in, it definitely has a more noticeable social scene aspect to it.”

I’m sure that’s the case. And The Rocky Horror Picture Show may well continue to serve its original purpose outside major cities – but for how long? With society and the pop culture that both reflects and shapes it pressing forward so quickly on issues of gender and sexuality, the movie and the cult it fostered seem doomed to… well, maybe not extinction, but novelty status. There’s a certain sadness to that, the kind that follows any radical subculture’s absorption into the mainstream. Ultimately, though, it’s good news that we’re finally starting to live in the world Rocky Horror created. It’s a more confusing world, one where cross-dressing and flexible sexuality might not create the transgressive frisson they once did. But it’s also a whole lot freer.