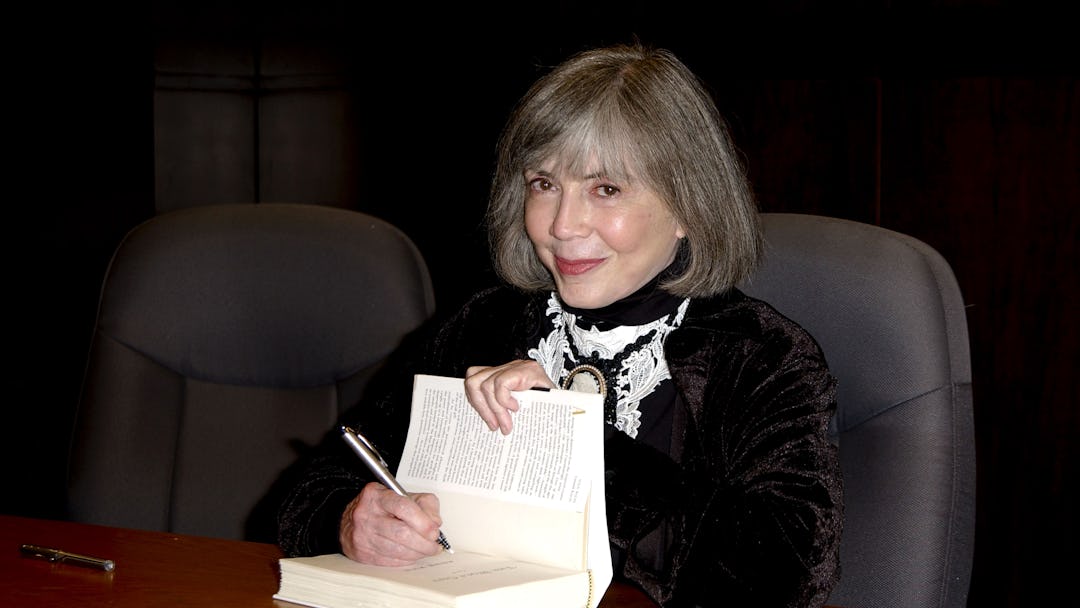

Happy birthday to one of the godmothers of gothic entertainment, Anne Rice. Before the era of Twilight and its sparkly undead, the best-selling author was dishing up decadent, dangerous vamps and witches for the horror fiction crowd.

“As a child, I saw this beautiful film, Dracula’s Daughter. . . . It was all about this beautiful daughter of Dracula who was an artist in London, and she felt drinking blood was a curse. It had beautiful, sensitive scenes in it, and that film mesmerized me. It established to me what vampires were—these elegant, tragic, sensitive people,” Rice said of one of her early influences.

Most people were drawn to Rice’s florid works when they were younger, so we’ve collected a number of other books that are sure to appeal to your inner teen goth.

Lost Souls, published as Poppy Z. Brite

Billy Martin, previously known as Poppy Z. Brite, made a smashing debut in the horror fiction world with 1992’s Lost Souls. Set in the South, featuring modern-day vampires who blur the lines of sexuality (with goth-friendly names like “Ghost”), Martin’s book is erotic, violent, and understands the angsty outcast who is often torn between the dark and light.

HR Giger’s Necronomicon, HR Giger

In May, we interviewed HR Giger documentary filmmaker Belinda Sallin about the Swiss painter and Alien designer, and her own discovery of his works

H. R. Giger’s Necronomicon is a gateway book for many artists and dark subcultures. I know you’re familiar with his work from your teenage years. What did the images symbolize for you back then, and has your view of the work changed since making the movie? In my youth, it was a bit like a rebellion. These pictures were uncommon. They were unusual. Adults, they thought it was disgusting. “How can you look at that?” It was a kind of position you take when you say, “I like that.” This changed a lot over the years, and now during filming, I engaged completely in another way with his art. I really appreciated that a lot. I started thinking what he wanted, why I am attracted to his art. And, of course, I found many, many answers. I can’t tell you all of them, but I think it’s really interesting that his art leads you to more philosophical questions or abstract questions. “What is fear?” for example. “What are my fears?” And so on. There are a lot of things I appreciate.

The Sandman, Neil Gaiman

Eternally black-clad author Neil Gaiman broke new ground in the comic book world with his clever, horror-tinged fantasy narrative about the anthropomorphic Dream and his older sister Death (who looks like Siouxsie Sioux), introducing graphic novel storytelling to a new generation.

Jhonen Vasquez’s comic series Johnny the Homicidal Maniac, with its stabby, over-the-top characters and Burton-esque illustration style, is more typical comic book reading fare (no shade) for the spooky-minded.

Interview with the Vampire, Anne Rice

Anne Rice’s iconic vampire novel, written after the death of her five-year-old daughter Michelle (the basis for vamp Claudia), is a bedside staple for any respectable young goth. Rice created a romantic, tragic, erotic, and gender-fluid historical saga — collectively known as The Vampire Chronicles — that she eventually spun into a tale about witches (her Lives of the Mayfair Witches series). The author’s undead are philosophical and full of longing, while the “pop sorcery” of her stories makes them effortless reads. If you’re feeling naughty, try Rice’s erotic Sleeping Beauty Quartet, published under the name “A. N. Roquelaure.”

The Satanic Bible, Anton LaVey

Anton LaVey, the granddaddy of all evil — a former pipe organist who made it big while giving talks about the occult to San Francisco’s freaky crowd during the 1960s — authored several books about his brand of Atheism and individualism. But the Satanic Bible is the heart of the LaVeyan Satanist movement — and it’s become a pop-culture symbol of dissenting opinion and anarchic behavior with its ominous black cover, striking Baphomet sigil, and in-your-face philosophies (it’s hard to resist stuff like “Satan represents vital existence, instead of spiritual pipe dreams!”).

The Gashlycrumb Tinies, Edward Gorey

Artist, writer, and theater designer Edward Gorey had a penchant for the dramatic, the morbid, and the morbidly humorous. His inky illustration style and Edwardian/Victorian decadence is the lifeblood stuff of dark darlings everywhere. The Gashlycrumb Tinies, Gorey’s alphabet book featuring a different character for each letter that succumbs to a miserable (but creative!) death, is essential reading.

The 120 Days of Sodom, Marquis de Sade

For some, the Marquis de Sade’s libertine writings about sex, violence, and other unmentionables are an endurance test (though we’d argue that Pasolini’s Salò probably takes the crown). Since you surely skimmed the book as a teen for the story’s most disgusting bits, reread it as an adult and decide if the suffocating passages with a sociopolitical slant are worth the grotesque orgies.

Carmilla, Sheridan Le Fanu

Instant goth cred can be yours by reading Sheridan Le Fanu’s 19th-century novella about a seductive female vampire who preys on young women. Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw were influenced by Carmilla. The story about a shapeshifting woman, who creeps into bedrooms at night as a cat (not very subtle, SLF), became the prototype for the lesbian vampire seen in films by British studio Hammer and others.

Dark Dance, Tanith Lee

The first book in Tanith Lee’s Blood Opera Sequence is basically V. C. Andrews for the spooky crowd, complete with incestuous storylines and family drama, an atmospheric setting, and plenty of dark thrills.

Carrie, Stephen King

We recently made a case for Stephen King’s 1974 novel, which is even stranger and more radical than you probably remember:

Carrie is a seriously weird piece of work. I first read it in my teens, and even then was rather taken aback by how unusual it was; when I revisited the book recently, two decades later, that first impression hadn’t faded at all. For a start, the book features a female protagonist (and largely concerns female characters) — an unusual move for a male genre-fiction novelist scrambling to sell his first book, and one that King wouldn’t repeat until Firestarter. It’s structured as an epistolary novel, an idea that King would never really use again, and its constantly shifting point of view tends to disorient the reader.

Books of Blood, Clive Barker

English author Clive Barker is perhaps best remembered for his 1987 film Hellrasier (based on one of his stories), about a young woman who opens a gateway to hell and is forced to fend off a group of sadistic “Cenobites” that threaten to “tear [her] soul apart.” In the literary world, Barker’s Books of Blood, six books hailed by Stephen King as “the future of horror,” display the writer’s twisted imagination and phantasmagorical style. Many of the stories have been adapted for the big screen, like Candyman and The Midnight Meat Train, but there’s visceral magic between the pages that few films have been able to fully capture.