Bad movies are not a simple matter. There are nearly as many categories of terrible movies as there are for great ones: insultingly stupid (Batman & Robin), unintentionally funny (Birdemic), unintentionally, painfully unfunny (White Chicks), so bad they’re depressing (Transformers), and so on. But the most rewarding terrible movies are those we know as “so bad they’re good” — entertaining in their sheer incompetence, best braved in numbers, where the ham-fisted dramatics and tin-eared dialogue become fodder for years of random quotes and inside jokes. And in this spirit, Flavorwire brings you this month’s Creed-inspired edition of our occasional So Bad It’s Good feature: the hilariously overwrought and comically jingoistic Rocky IV.

The great opening shots of cinema are small artistic miracles, captivating us with their aesthetic beauty, plunging us into the physical world of the narrative, underscoring the themes we’ll spend the next two hours exploring. Think of the snow globe falling from the hand of the dying title character in Citizen Kane, the yellow cab emerging from the smoke and filth of Gotham in Taxi Driver, the rising of the earth and the sun in 2001. And, of course, think of the iconic images that open Rocky IV: giant close-ups of two boxing gloves, turning to reveal one emblazoned with the hammer and sickle and star of the Soviet Union flag and the other decked out in the stars and stripes of the USA! USA! USA! The two gloves face off, charge at each other… and explode.

There’s so much to love about this opening, it’s hard to even know where to begin: the fetishism of the photography, the simplicity of the symbolism, the resurrection of Rocky III’s hit single “Eye of the Tiger.” But what I like best is the image of the title design company pitching this opening to writer/director/star Sylvester Stallone; I’d like to think they only had the flag-gloves thing in mind, to which he smiled and added, “Yeah, but what if they, like… exploded?” (And then there were presumably high fives and eightballs all around, this being the ‘80s.)

That said, at the time when he was making Rocky IV, you could understand his logic. When it hit theaters (and cleaned up) over Thanksgiving weekend of 1985, Stallone was at the height of his powers: his Rambo: First Blood Part II was one of the biggest hits of the previous summer, more than tripling the grosses of 1982’s First Blood, the actor’s first non-Rocky hit. And Rocky was one of the era’s most durable franchises, with Rocky III’s $125 million gross the series’ best. Rocky IV would top even that.

But in a strange way, Rocky IV feels less of a piece with the other Rockys than with Rambo and 1988’s Rambo III — Stallone’s Cold War trilogy, in which he singlehandedly takes on the Commies and leaves them quivering for mercy. Here, quintessential American success story Rocky Balboa takes on Ivan Drago, a Soviet super-athlete, and takes down not only that Russkie killing machine, but any doubts of American exceptionalism. He basically topples the Berlin Wall four years early (and in only 90 minutes).

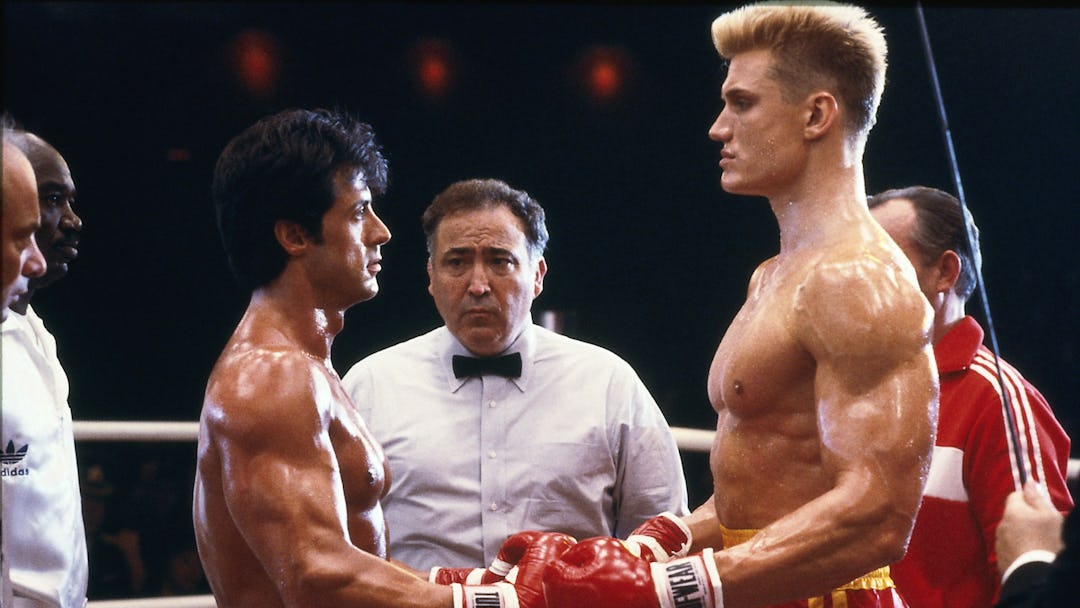

All that comes later, though. First, in the series’ usual telenovella form, Rocky IV begins with the end of Rocky III, as “the Italian Stallion” brings down Clubber Lang (Mr. T), with the help of rival-turned-trainer Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers, who unfortunately never has the opportunity to get a stew goin’). After some character comedy at his brother-in-law Paulie’s depressing birthday party — Rocky and Adrian give Paulie a robot with an A.I. capacity decades ahead of its time, an odd detour into science fiction that apparently inspired Kermit’s “80s robot” in The Muppets — we meet our villain, Drago. He’s a marvel of modern technological malice (“Whatever he hits, he destroys,” sneers a handler), and there’s something about him that rubs ol’ Apollo the wrong way. So he decides to come out of retirement to take on the Russian monster, but after a contentious press conference (is there any other kind in boxing movies?), Stallone clumsily foreshadows his fate by having Drago take down a cardboard cutout of Apollo.

James Brown shows up at the exhibition bout to perform his worst hit ever, “Living In America,” alongside showgirls decked out in red, white, and blue. Apollo was always a showman, though in the face of such goofy flag-waving, it’s worth remembering the character was initially inspired by Muhammad Ali, whose own patriotism was a bit more complicated. Anyhoo, Drago sneers, “You vill lose,” and Creed does; in fact, he beats the champ literally to death, and Rocky finds himself cradling his dead friend in the ring as interviews are conducted over his shoulder. It’s a weird scene!

Rocky hastily arranges a revenge fight, announced at another contentious press conference, in which Stallone’s clunky dialogue is clearly meant to suggest that Drago symbolizes nothing more complicated than Communism itself (“Drago is a look at the future!”). The fight will happen on Christmas Day, in the Soviet Union, and Rocky will take no money for the bout — a questionable decision, considering the kind of financial trouble his family is in by Rocky V. (C’mon, Rock, the property tax on that giant fuck-off mansion ain’t gonna pay itself!) He returns home for a terse stairway argument with ever-supportive wife Adrian, who screams, “You can’t win!” and storms off.

Like we all do, Rocky goes for a drive in his sportscar to clear his head and puzzle out his motives, which are illustrated by clips from all the Rocky movies, including the one we’re watching. This is not an exaggeration; one of the images in Rocky’s head is of Adrian walking away from him at the top of the stairs, which happened like a minute a half earlier. (The whole sequence is in danger of lapping itself.) It’s not just that this is a musical montage — it’s a music video, playing an entire song to the label (and the shots from the movies make it feel even more like one, like we’re watching an MTV clip from the soundtrack album).

This musical montage has barely ended before another begins, with Rocky’s arrival overseas, followed by two consecutive training montages (separated by the absolute minimum of dialogue). The lyrics are hilariously on-the-nose: “The moment of truth is here”; “There’s no easy way out”; and, no exaggeration, “Seems our freedom’s up against the ropes!” And the ironic counterpoints are equally unsubtle; Rocky basically does chores, bulking up (and re-growing his Nighthawks beard) via good old-fashioned American elbow grease, while Drago is hooked up to computers, run through machines, and juiced up (our subsequent knowledge of Stallone’s own encounters with steroids make this juxtaposition tougher to pull off). Rocky’s tractor-pulling and wood-chopping program culminates in a run to the top of a mountain, a desperate attempt to ape the most iconic scene of the first film, and then it’s time for the big fight scene.

So not only is the film’s entire second act comprised of montages, but with the third act turned over to the Rocky/Drago ‘bout, I’d hazard a guess that maybe, maybe 30 minutes of Rocky IV is spent on people talking to each other. Based on the dialogue we get, that’s no giant loss — but it is startling, particularly when you compare Rocky IV to Rocky I. That film was mostly people talking; it’s a delicate, finely tuned character study about desperate people and dead-end lives and last shots, in which our hero doesn’t even start training until the last half hour, and the closing fight clocks in at less than ten minutes. This doesn’t just seem like a movie from a later era. It seems like a movie from another universe.

Anyway, Rocky somehow manages to best his opponent, to such a degree that (snort) the all-Russian crowd begins chanting his name, and (double snort) the Gorbachev doppelganger stands to applaud him. Something tells me a trip to Siberia would’ve been the more likely result, but no, everyone’s ideology is destroyed by this barely literate boxer, who announces, while literally draped in the American flag, “If I can change, and you can change, everybody can change!” One envisions a Rocky V where Balboa leads the second Russian Revolution, but alas, no dice; we just get an end-credit montage of stills from the movie we just watched, like it’s the end of an episode of M*A*S*H or something.

If Rocky IV found Stallone at his peak, it was also the beginning of the end; it was his last movie to top $100 million for nearly 20 years, as a series of box-office disappointments (Cobra, Over the Top, Rambo III, Lock Up, and Tango & Cash) did considerable damage to his stardom by the end of the decade, a nosedive that even Rocky V couldn’t slow. The series wouldn’t get its legs back until 2006, when audiences and critics embraced the back-to-basics Rocky Balboa; the new spin-off movie Creed (in which Stallone co-stars but, for the first time, doesn’t write) is getting the series’ best reviews since the first one.

Yet Rocky IV still stands, not as a highlight of the series (certainly not that) but as a quintessential artifact of mid-‘80s studio filmmaking: soulless, flag-waving, soundtrack-blasting Product. Between the slender 90-minute running time, the montages and clips from other movies, and the written-in-a-weekend nature of the screenplay, it’s about as cynical a motion picture as was made in that grotesquely cynical era. It was a time when people would go see just about anything with the word Rocky in it — and Rocky IV proves it, over and over and over again.

Rocky IV is streaming on Netflix. Special thanks to fellow Bad Movie aficionados Mac Welch, Brenda Welch, Kyle Bruno, Amber Malott, and Rebekah Dryden.