Welcome to “Second Glance,” a new bi-weekly column that spotlights an older film of note (thanks to an anniversary, a connection to a new release, or new disc or streaming availability) that was not as commercially or critically successful as it should’ve been. This week, in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of its release, we pay tribute to Joe Johnston’s charming superhero adventure The Rocketeer.

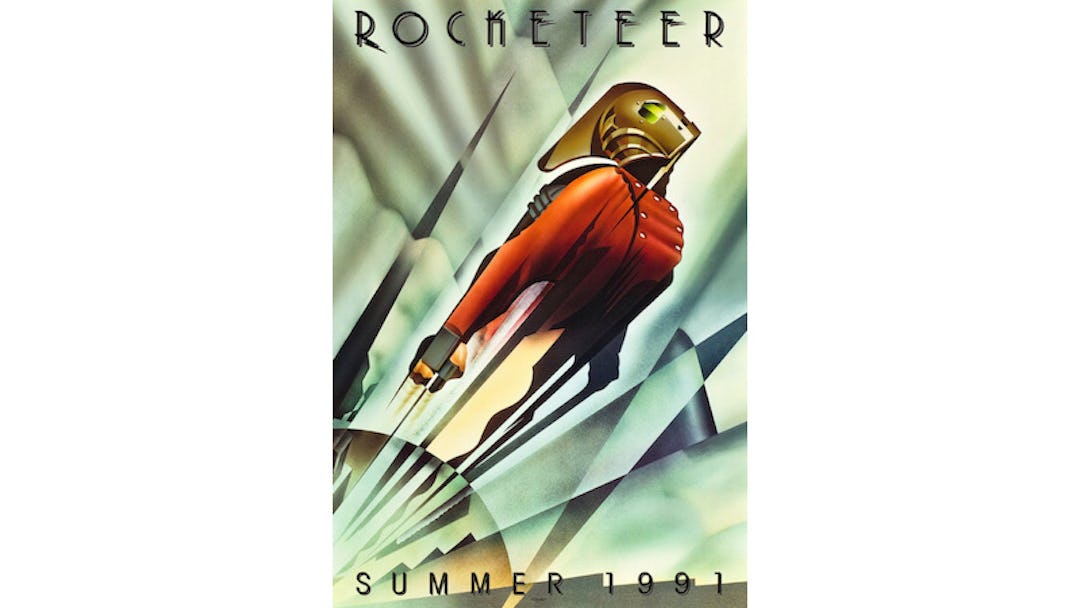

When Walt Disney Pictures shipped prints of The Rocketeer to theaters in advance of its opening on June 21, 1991, they were also sending their hopes for a shiny new franchise. And the film, based on the comic book character created by Dave Stevens nine years earlier, had all the right ingredients: the period setting and bright pop style of Dick Tracy (Disney’s funny-pages hit of the previous summer), crossed with the Saturday serial homage of the Indiana Jones movies (specifically the adventures of Commando Cody, the helmeted, jetpack-powered hero of two Republic serials which later appeared on Mystery Science Theater 3000).

But without the star power or cultural ubiquity of those pictures, The Rocketeer sputtered and spiraled to earth; it opened in fourth place, behind second-week Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, third-week City Slickers, and its fellow opener Dying Young (a Julia Roberts vehicle so lame, no one even dies young). Its $46 million domestic total barely covered its $35 million budget, so suffice it to say, there would be no Return of the Rocketeer. But in the quarter-century since its release, as the superhero blockbuster (and particularly the superhero origin story) has become a cornerstone of mainstream moviemaking, it’s become clear that The Rocketeer is a model of the form – breathless, energetic, and endlessly entertaining.

The director was Joe Johnston, the former visual effects artist (he won the Oscar in that field, coincidentally enough, for Raiders) who’d made Disney a mint two years earlier with the effects-heavy family comedy Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. Rocketeer, set in 1938, is the story of Cliff (Billy Campbell), a daring yet kind pilot whose big test flight is disrupted by a car chase, a couple of explosions, and a bait-and-switch. After the smoke clears, Cliff and his partner/mechanic Peevy (Alan Arkin) find themselves in possession of a rocket pack, stolen from Howard Hughes (Terry O’Quinn) and desired by the U.S. government, gangsters, Nazis, and Errol Flynn-esque movie star Neville Sinclair (Timothy Dalton).

Those name-drops give a sense of how The Rocketeer’s script (adapted, from the original comics, by Danny Bilson and Paul De Meo, who also wrote for the original 1990 TV version of The Flash) cheerfully interweaves real figures and WWII history with its fantastical narrative. They also indicate the filmmakers might’ve overestimated the mass summer audience’s grasp of such references – for example, a big deal is made of Neville introducing Jenny to W.C. Fields, a scene that (to this fan’s chagrin) probably left many a summer moviegoer scratching his/her head.

But they’re essential to the world of the movie. We get an idea of who Cliff is early on, when he’s pulled from the cockpit of his soon-to-explode plane, yet runs back to grab the snapshot of his best girl Jenny (Jennifer Connelly) he’s stuck to the instrument panel. He’s the good guy, and there’s no ambiguity about it, which is in many ways the key to The Rocketeer’s appeal. It’s not just period in its setting – it’s period in its style, its tone, its attitude. There’s a spirit of innocence to the movie, a gee-whiz enthusiasm often absent from the calculated, airless blockbusters of the era (and today). Every character in it has a singular, defining quality: brave hero, supportive sweetheart, funny buddy, gangster, villain, etc. Everyone is pretty much exactly the same at the end of the movie as they are at the beginning; everything you need to know about its shades of grey is found in the scene where baddie Sinclair kidnaps Jenny and, while trying to seduce her, asks her to change from her preferred snowy white dress to a skimpy black number. (She’s not having it.)

This kind of thing can get tiresome in large doses, granted. But viewed from our distance, immersed as we are in the current mold of “gritty” comic book interpretations like the joyless Batman v Superman , it’s a breath of fresh air. First-time viewers will find plenty to giggle at here – its effects, for example, haven’t aged well (even compared with other films of its time, like that summer’s T2), but if anything, they add to the movie’s charm. Johnston’s action beats are thrilling but also funny, Dalton’s dastardly villain turn (one of his first big roles after fumbling in two lesser Bond movies) is a delight, and Connelly’s never been more likable (or unreasonably beautiful).

Near the end of The Rocketeer, there’s a moment where our hero launches from atop a building with Old Glory flapping behind, propelled as much by James Horner’s triumphant theme as by his rocket pack, blasting up to take down a Nazi zeppelin. It’s a beat that’s aware of, and winking at, its own corniness – and also transcending that corniness to work on its own terms. Twenty years later, Disney (via Marvel) hired Johnston again, to direct another period superhero film, the first Captain America. It was far more commercially successful, and remains one of the best films in that particular Cinematic Universe. But The Rocketeer did it first, and better. It was, and remains, a blast.

The Rocketeer is available on DVD and Blu-ray, and via Amazon, iTunes, YouTube, and the usual on-demand outlets. Next week, we revive our “Bad Movie Night” column with the original Independence Day.