When Madonna went on the road in 1990 for her “Blonde Ambition” tour, she was one of the most famous people in the world, but she was in need of a career invigoration. Her last couple of albums hadn’t lit up the world the way the first flush had; her tempestuous marriage to Sean Penn had dominated the tabloids, distracting attention from her creative endeavors; her attempts to follow up the success of her film debut Desperately Seeking Susan had crashed and burned with increasing force. But when she took that show into the world, she had a hit movie in the can (Dick Tracy), a famous new beau (that film’s director/star, Warren Beatty), and a smash single on the charts (“Vogue”). And she invited along music video director Alek Keshishian to document the opening of her second act. The movie he made, Madonna: Truth or Dare, certainly did that. But seen now, on the 25th anniversary of its release (with a new restoration engagement beginning tomorrow at New York’s Metrograph), Truth or Dare is much more than your conventional tour documentary.

But it certainly does that specific thing well. Keshishian shoots the performance scenes with infectious energy and fleet feet, treating them less like concert performances than classic Hollywood musical numbers, showcasing the skillful inventiveness – and often military precision – of Madonna and her crew of back-up dancers. “Holiday” and “Keep it Together” are particularly striking; it’s easy to forget, from this distance, how mesmerizingly she moved, how she meshed with this group of (younger) dancers, most of whom weren’t singing at the same time. Those tightly choreographed numbers and highly theatrical staging techniques would become the norm for big pop shows; Madonna, as usual, got their first, and Truth or Dare showcases impressively the bar that she set.

But that’s not what we remember about this film. We remember the backstage footage, the documentary stuff, lensed mostly by Richard Leacock, the founding member of the “direct cinema” movement whose credits included Primary, Monterey Pop, and Norman Mailer’s Maidstone. And in contrast to the slick camerawork and bright colors of the concert scenes, the backstage footage is shot in grainy, 16mm black-and-white – not out of the equipment and budget constraints that Leacock, Al Maysles, and the rest of their direct cinema brethren were saddled with, but because of what that aesthetic signals: realness, documentary intensity, warts-and-all portraiture.

And from our vantage point, it’s vital to consider how conventions of the documentary were being repurposed here. Those of us who abhor reality television have always felt a little bit of discomfort about how closely it brushes with the stylistic conventions of documentary cinema: the handheld “fly on the wall” camerawork in everyday conversations, the direct-to-camera talking heads interviews to fill in the gaps, etc. The year after Truth or Dare debuted, MTV would premiere its reality TV groundbreaker The Real World, and it’s not hard to trace its style to Keshishian’s film – the musical montages, the real-but-sorta-staged confrontations, and especially the “confessional” to-camera interviews, in which Madonna shares personal insights, like how her dancers and staff are “people who need mothering, in some way. I think it comes naturally to me.”

But it’s also hard to ignore that the introspective yet breathy voice she adopts in the voice-overs and interviews is markedly different from her everyday speaking voice; it’s clearly a performance, a feeling that reverberates through Truth or Dare. By this point in her career, seven years into her mega-stardom, no one is more aware of the camera, and even when it’s “eavesdropping” on her being the boss (technical glitches keep cutting out her mic but not her back-up singers’, to which she roars, “Put me on their fuckin’ frequency!”), or capturing a “private moment” like her de-glammed in a shower cap, eating soup and talking on the phone to her dad, there’s no question that this, too, is all part of the big show.

The big show involves singing and dancing, sure, but also stripping (a moment of pure calculation that got more than one teenage boy into the theater – hello), flirting, preening, and soapboxing. She responds to her dad’s request to “tone it down” for her hometown show by objecting, “that would be compromising my artistic integrity”; later, she tells her dancers that she won’t honor a similar request from local police because “In the United States of America, there is freedom of speech.” This is at a gig in Toronto, but you get the idea.

Those controversies – over simulated masturbation in her “Like a Virgin” number – seem so quaint in 2016, when such a scene could play on network afternoon TV, but that’s about the only dust on Truth or Dare. Most of the music still holds up; even the songs that don’t, like “Vogue”, are imbued with nostalgia. And it’s an important song for the movie, not just because it was a giant hit at the time, but because by this point in Madonna’s career, “strike a pose” was less a lyric than a mission statement.

So she invests the character of “Madonna” with silliness, lightness, depth, nastiness – the complexity of a “real” person, who she may or may not be. And that’s what’s always such a riddle about that chameleonic persona, constantly reinventing yet still undeniably her: it could be the real Madonna. Or it could be a carefully constructed version of who she wants us to think she is. Or, most tantalizingly, it could be what she wants us to think she wants us to think she is. You see how the snake can eat its own tail here, and at a certain point, it doesn’t even matter; lines blur, person becomes persona, and text becomes subtext. The question of “Who is the real Madonna?” has long since become our placeholder for the entire notion of “the real Madonna.” And you get the feeling that’s entirely by her own design; after all, over 30 years after her emergence, the notion of a film that shows us the real, unguarded Madonna Louise Ciccone is still tantalizing.

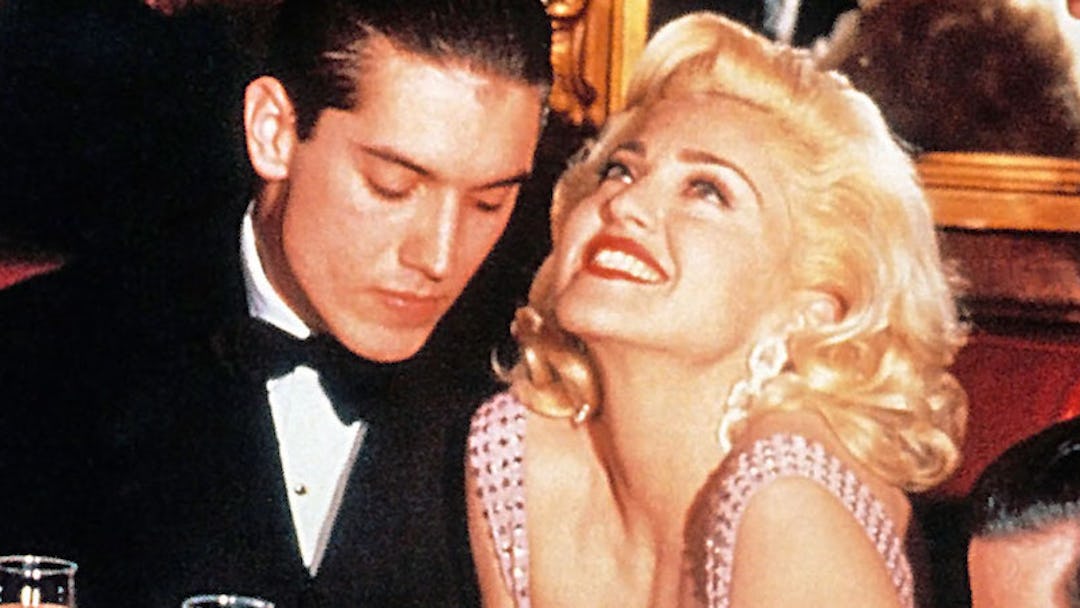

Madonna was 32 years old when she was on this tour, but in a lot of ways, she’s still a goofy kid, reciting her “fart poem” and saying, as we all did in that Wayne’s World-obsessed era, “NOT!” a lot, to the clear irritation of the much older Warren Beatty. He’s a fascinatingly spectral presence in Truth or Dare, spotted early on hanging out in her dressing room, playing the back, barely saying a word, even as she busts his balls. Later, when he accompanies her to an appointment with her New York throat doctor, he’s befuddled that Keshishian’s cameras have come along as well; in that scene, he’s the one who comes closest to breaking the specific type of fourth wall she and the filmmaker have constructed, remarking on the “insane atmosphere” everyone in her life feels when they come into these documentary scenes. “She doesn’t wanna live off-camera,” he shrugs. “What point is there?” They break up not long after – off-camera.

But based on the divergent paths of their fame in the years that followed, it’s hard to argue with the effectiveness of her strategy. Truth or Dare plays, now more than ever, like a Nostradamus-esque prediction of what celebrity culture would become – the kind of openness and access we would require of our super-stars, even if the version of themselves was decidedly focus-grouped and calculated. It’s impossible to imagine something like Keeping Up with the Kardashians without the precedent of Truth or Dare; when celebrities beef on Twitter or Instagram, it’s easy to forget how shocked everyone was when Madonna (who, it must be noted, was executive producer) let them leave in scenes where she shit-talks Oprah or freshly-Oscared golden boy Kevin Costner. But she wasn’t there to make friends, she was there to win. And in Truth or Dare, Madonna, as usual, was way ahead of her time.

Madonna: Truth or Dare begins its revival run tomorrow at NYC’s Metrograph. It’s also available to stream or purchase on Amazon, iTunes, and the usual platforms.