Welcome to “Second Glance,” a bi-weekly column that spotlights an older film of note (thanks to an anniversary, a connection to a new release, or new disc or streaming availability) that was not as commercially or critically successful as it should’ve been. This week, timed to the Blu-ray release of the Prince Movie Collection, we look at Prince’s Purple Rain follow-ups, Under the Cherry Moon and Graffiti Bridge.

Prince wasn’t exactly an obscurity when Purple Rain took over the American media landscape in 1984, but its three-pronged approach – a wide-release motion picture, a bestselling album, and singles dominating the radio – made him ubiquitous in an altogether new and exciting way. This was the power of the jukebox musical, from Love Me Tender and A Hard Day’s Night forward; it was one thing to hear your favorite artists’ songs, or see them performed on television, but it was quite another to see them several feet tall on a cinema screen, sharing not only their music but something resembling their personality.

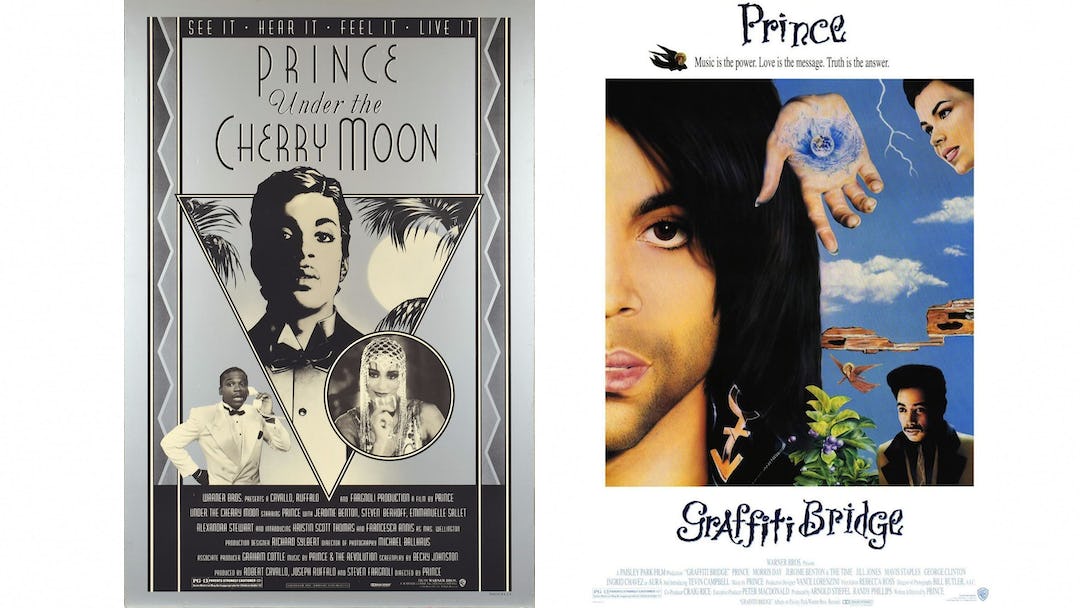

And so it was with Purple Rain, which was not only a reasonable critical success but a giant commercial one, grossing over $68 million on a $7.2 million budget. But that marked the beginning and the end of Prince’s cinematic success; his 1986 follow-up, Under the Cherry Moon, cost more but grossed far less ($10 million), and his third and final feature film vehicle, Graffiti Bridge, grossed less than half of even that. What’s worse, both films were roundly panned by critics, and rejected by fans. Those failures must’ve particularly stung because of his increased creative control – while he certainly helped shape Purple Rain, Cherry Moon was his first directorial credit, and Bridge his first as writer/director. Now, as all three films hit Blu-ray in the posthumous Prince Movie Collection, it’s worth asking: did everyone get it wrong?

Set in the gorgeous French Rivera (the production designer is the great Richard Sylbert, of Chinatown and The Graduate) and shot in cool, stylish black and white by Scorsese’s frequent cinematographer Michael Ballhaus (Raging Bull, Gangs of New York), Under the Cherry Moon finds Prince teaming up with Jerome Benton – member of the Time, and Morris Day’s second banana in Purple Rain – to play brothers swindling rich, lonely French women. The tone is established early; he’s playing piano in a swanky nightclub, a woman comes in with a dress slit to there, and the broad, almost mugging takes as he observes her legs are less Purple Rain’s Kid and more Bob Hope.

Prince spends the picture making faces in mirrors, doing wild bits with Jerome (“That’s right, cousin, do that Bela Lugosi look!”), and even dipping his toe into the waters of bedroom farce. Reviewers of the time seemed to seize on the desaturated photography and his directorial aspirations (“‘a film by Prince’ sounds like a German shepherd’s home movie,” sneered People) and determined that Cherry Moon was some kind of pretentious “vanity project” – a phrase, as others have noted, that never seems to get thrown at white male filmmakers. But the black-and-white, as with so many music videos of the era, is employed because it’s striking and cool-looking, and as far as his ambition, well, maybe film critics just didn’t know much about Prince. But mostly, it’s strange that so few seemed to understand that it’s a silly film, purposefully so, and tried to use their prose to laugh at the film – as if Prince weren’t laughing way ahead of them. He was telling the joke.

As a director, his frames are vibrant, and his style is energetic; the only real disappointment is how few actual musical numbers there are (there are plenty of songs, but they’re mostly background and score). Becky Johnston’s screenplay is trafficking in clichés, but winking at them, and the director mimics that approach; the whole film is performative, false in a conscious way, like overgrown kids having fun playing dress-up. His leading lady, Kristin Scott Thomas (in her feature debut), has since spoken of the project with something less than kindness, but she’s playful and sexy, her accent dripping like honey, gamely going along with their characters’ many – and I do mean many – vacillations between love and hate. My personal favorite bit of dialogue is this exchanging of insults:

Her: Punk!

Him: Brat!

Her: Gigolo!

Him: Cabbage-head!

That dumb People review insists, “It’s all but impossible to take this film seriously,” but how can you assume any movie with that dialogue wants to be taken seriously? Sure, it’s dopey and soapy and its ending is jarringly melodramatic. And that seems to be exactly what its creator was going for.

After Cherry Moon’s commercial failure and critical roasting, Prince understandably went for safer ground. 1990’s Graffiti Bridge is, in all but its title, the sequel to Purple Rain, with Prince returning to the character of “The Kid” (as well as writing and directing), and Jerome Bentley resuming his place at the side of cackling villain Morris Day and their group The Time. The plot is a pretty silly bit of business, finding the gangster-like Day owning every nightclub on “the Seven Corners” except The Kid’s, which he and his crew attempt to shut down before The Kid finally pushes back by challenging The Time to a musical battle with his group, the New Power Generation. Oh, and there’s some silliness with a muse-like angel, played by Ingrid Chavez – a role written for Madonna, who reportedly turned it down because the script was a “piece of shit.”

She’s not exactly wrong, but it doesn’t much matter. The screenplay doesn’t need to achieve Cheever-like penetration; it needs to hold together the music, and it does that job fine. Prince’s direction is even sharper this time around, heavy on the Dutch angles, wild lenses, and energetic editing of the concurrent Black New Wave, and he fuses his musicality with his filmmaking even more sharply (witness the wonderful scene where the Time guys follow Morris’s taunts with imitations of the string hits that are happening simultaneously on the soundtrack).

Like Purple Rain, Graffiti Bridge has a lot of trouble with its women (the Madonna/whore complex is strong with this one), and it gets more than a little sappy at the end. But the guest performers are terrific – Tevin Campbell, George Clinton, and especially Mavis Staples – and the director seems to have learned at least one thing from his previous effort: there is no shortage of songs here, and they’re fucking magnificent. He abandons even the semi-realism of Purple Rain for something closer to a good, old-fashioned, backlot musical – something we get even less of these days, so enjoy the novelty.

That speaks, once again, to the artist’s considerable ambition – and also to his affection for the cinematic form, one that he unfortunately either did not choose or was not allowed to return to over the last quarter-century of his life. At least we have these films, mocked in their time, and certainly far from perfect, but reminding us that in this medium as well, Prince was often up to more than it seemed.

The Prince Movie Collection is out tomorrow on Blu-ray.