Flavorwire is taking the final week of 2017 off, because God knows we need it. But all week, we’ll be reposting some of our favorite pieces from the year. Read them all here.

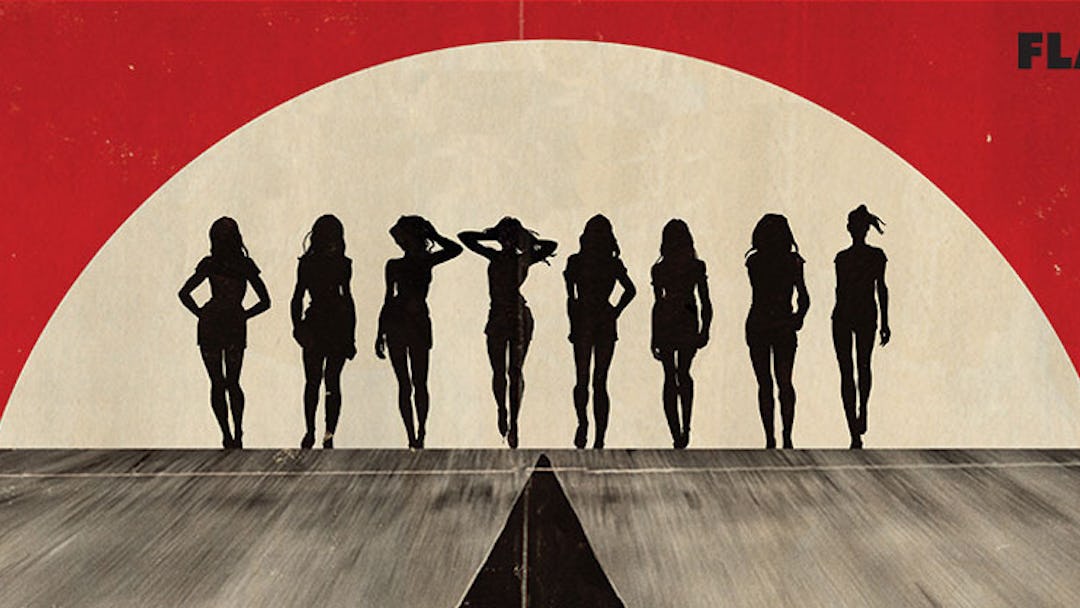

For better or worse, Quentin Tarantino is our master of the revenge flick. He’s made movies about black slaves turning on their masters and Jewish Americans avenging the torture and extermination of their European brethren. If Jackie Brown and Django Unchained were based on Blaxploitation films like Foxy Brown (1974) and Mandingo (1975), then Death Proof — released ten years ago today — is Tarantino’s tribute to the exploitation films of the 1960s and ’70s, films that feature bodacious women who drive fast cars and kick ass while their breasts heave.

Female characters who commit acts of violence are often wild, untamed things; usually, the implication is that they need to be restrained both sexually and physically, that their predilection for violence is a gender abnormality, accompanied by a dangerous desire to get down. Death Proof dangles this narrative line in front of its audience, and then throws it back in our faces.

In her 1995 book The Scandal of Pleasure, the critic and English professor Wendy Steiner writes, “Art evokes reality by being like it but not identical to it.” Death Proof evokes this sense of near-reality in its throwback aesthetic: It was made to look like the kind of movies that would play in old grindhouse cinemas in the sketchy part of town, yet it takes place in the present day. The movie is filled with intentional flubs, like “missing reels” and awkward cuts between frames. Its surface looks scratched, as if the film has been passed through one too many cruddy projectors. The jarring cuts and intentionally choppy edits give the film a haphazard, slapped-together feel — something with pretty girls and a car crash, emphasis on the gore and close-up shots of female body parts.

Death Proof premiered as part of a double feature called Grindhouse, which gave cinemagoers two movies for the price of one: Robert Rodriguez’s Planet Terror, a faux-1970s horror film, and Death Proof, which itself is split into two fragments. In the first, psychopathic Stuntman Mike, played by Kurt Russell, stalks a trio of young women on a night out before fatally crashing into them with his tricked-out stunt car — it’s “death proof,” he explains, but you have to be in the driver’s seat to get the car’s full benefit.

In the second half, Stuntman Mike meets his match: Another trio of women — two of them stuntwomen themselves, the other a makeup artist — working on a film shoot in Tennessee. Their day starts with going to the airport to pick up Zoë, played by real-life stuntwoman Zoë Bell, and ends with Stuntman Mike pursuing them on a wild car chase. By the end of the film, Mike is the one begging for mercy. When the girls finally catch up to him, they drag him out of the car and beat him to death.

* * *

When Death Proof opened in the United Kingdom in September 2007, women’s advocacy groups protested in front of the Glasgow Film Theatre, urging the cinema to suspend its screenings of the film. Catherine Harper, the founder of Scottish Women Against Pornography, told the Scottish newspaper The Sunday Herald , “I’ve nothing against Tarantino, but the film’s not helpful, and unless action is taken against things like this, the dehumanizing of women will seep into the psychology of everyday life.”

The question is: what kind of Hollywood film did Harper think would end gender violence? Movies may have lingering effects on the way people live their lives, but it’s certainly not the job of the entertainment industry to solve the problem of low conviction rates for Scottish rapists. As Steiner argues, “The fact remains that the Playboy reader is holding only a representation in his hands, and that people — not dirty magazines — terrorize women.”

Writing about the film in The Guardian at the time of its premiere, Kira Cochrane, then the paper’s women’s editor, complained that Death Proof is part of a “trend towards the mainstream depiction of women as highly sexualized bait and prey.” That trend is hard to deny, but Cochrane’s description leaves out an important aspect of the movie: the revenge fantasy, a staple of Tarantino’s films. Women onscreen are often punished for wild behavior — and the first half of Death Proof, in which the girls are killed after a night of drinking, dancing, and smoking pot, seems to follow this narrative line. But the film is structured so as to give the women the last laugh: when the girls kill Mike at the end of the second half, it’s a gleeful moment that ends with a group high-five before the credits roll.

Compare that triumphant ending with the treatment of the three women in Russ Meyer’s classic 1965 exploitation film, Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! The movie centres on three go-go dancers with comically large breasts who race through the desert, leaving a trail of havoc in their wake. The women meet a clean-cut, all-American couple, and challenge the man to a race. When he loses, he gets into a fight with the group’s ringleader, Varla (Tura Satana), who judo-chops him to death. The trio kidnaps the dead man’s girlfriend and speeds off until they find an old man who is said to have money stashed away at his ranch. They scheme to get the money, but their plans go awry and all three end up dead.

Tarantino’s debt to Faster, Pussycat! is evident throughout Death Proof. Like Meyers, Tarantino shoots his women from low angles, giving them the stature of Amazon warriors in bootie shorts. One character from Death Proof’s first half wears a t-shirt featuring the image of Tura Satana wrestling that all-American man to the ground in Faster, Pussycat!. And the final scene of Death Proof, in which the stuntwomen and the makeup artist beat Stuntman Mike to death in the middle of rural Tennessee, is a clear homage to the fatal beating Varla administers to the hapless man in the desert.

In Faster, Pussycat!, the women’s penchant for violence is practically arbitrary — Varla’s murderous act seems like an afterthought. But the women of Death Proof have good reason to be wary of men. The three women in the first half plan to drive to a lakeside cottage belonging to one of their fathers, but they insist there will be “no guys at the lake house.” Every male character in the film is suspect, from the two bar patrons in the first half who scheme to get the girls drunk to the grunting, racist owner of a Dodge Challenger in the second half, who begrudgingly lets the girls take his car for a test drive under the assumption that they’re going to buy it. Before they pick up the car, the girls stop at a diner for breakfast, where Kim (Tracie Thoms) explains why she carries a gun: “I don’t know what futuristic utopia you live in, but the world I live in, a bitch need a gun.” When one of her friends suggests pepper spray as a less violent alternative, Kim shoots back, “Motherfucker try to rape me, I don’t want to give him a skin rash!” She doesn’t just want to prevent her abuse: She wants to teach her attacker a lesson.

Kim is unapologetic about her gun, and Tarantino rewards her and her friends by ending the movie after they’ve killed Stuntman Mike, instead of portraying the consequences of their crime. But other films of the 1960s and ’70s — the B-movies that Death Proof riffs on — are not so eager to justify their female characters’ violent impulses. In The Warriors (1979), the title gang meets an all-female mob called the Lizzies who invite their male counterparts to hang at their apartment. This seduction turns out to be a ruse, and the Lizzies attempt to kill the Warriors. Of course, the women are all lousy shots, so the Warriors get away, but not before the softest and youngest among them is injured. Director Walter Hill doesn’t include one frame of a woman getting in a punch, but there are plenty of shots of the Warriors nimbly defeating their weaker foils.

Tarantino allows his female characters to land more than a few blows. You could argue that he does something similar to what Steiner accuses Andrea Dworkin of doing in her 1990 novel, Mercy. That novel tells the story of Andrea, a woman who endures constant physical and sexual violence over her lifetime and eventually attempts to mitigate her agony by killing men. In her critique of the novel in The Scandal of Pleasure, Steiner points to an unresolved contradiction: The violence that men perpetuate turns out to be the only way to alleviate the protagonist’s pain. So Andrea kills men, a twist of events that Steiner calls “intolerant, simplistic, and often just as brutal as what it protests.”

Are the women of Death Proof just as brutal as what they protest? Is Tarantino’s fantasy an imagined corrective to gender-based violence, or just another form of it? Feminist critic Ellen Willis, who died in 2006, might have favored the latter interpretation. In a 1977 Village Voice article, “Beginning to See the Light,” Willis writes about her ambivalence toward punk rocker Patti Smith: “I’m also uncomfortable with her androgynous, one-of-the-guys image; its rebelliousness is seductive, but it plays into a kind of misogyny…that consents to distinguish a woman who acts like one of the guys (and is also sexy and conspicuously ‘liberated’) from the general run of stupid girls.” Her description of Smith could certainly apply to the women of Death Proof: Stuntwomen Zoë and Kim are self-proclaimed “gearheads,” berating the other girls for preferring John Hughes’s Pretty in Pink to classic car-chase movies like Vanishing Point.

In the same article, Willis goes on to express her doubts about “an alternative women’s culture,” writing, “For me feminism meant confronting men and male power and demanding that women be free to be themselves everywhere, not just in a voluntary ghetto.” A Quentin Tarantino movie is certainly no women’s ghetto. Yet while Death Proof doesn’t skimp on the gore, it also features long stretches of uninterrupted conversation between the girls. Some who reviewed Death Proof complained about the inclusion of so much unalloyed female conversation. In his review in The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw longs for the manly banter of Tarantino’s earlier films, writing, “Tarantino has had to pad this film with stuff that would hardly make the DVD’s ‘deleted scenes’ section: long, long, long stretches of bizarrely inconsequential conversation between the babe avengers which are a big comedown from the glorious riffs from Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction…But check out that head-on collision.” In other words: Can’t we skip past the girl talk to the part where the dismembered limbs go flying through the air? For Bradshaw, two guys in suits talking about a Big Mac counts as “glorious” but a woman who talks about carrying a gun to do her laundry late at night is a drag.

If Death Proof is Tarantino’s fantasy of what women talk about when they get together, it’s a pretty great one. Those “long, long, long” conversations take on a loping, aimless rhythm that mirrors the pulse of the film itself. Perhaps they make Bradshaw uneasy in part because these lengthy girl-on-girl chats are not something we see too often in movies. It feels like watching an actual group of women talk about their lives: How far they’re willing to take things with the men they’re dating, their plans for the evening, how they’re going to score pot. (Not through any men: “We don’t score ourselves, we’re gonna be stuck with them all fucking night.”) With the exception of Rose McGowan and Rosario Dawson, Tarantino cast relatively underexposed actresses to play the lead women. It’s hard to place them in the context of other films, which makes their intrepid characters feel both true to life and super-human. They’re tough, quick-witted women who are simultaneously powerful, unapologetic, sexy, fun, angry, and reckless. They do whatever they feel like doing. And they look so cool doing it.

The fact that Tarantino allows these women to be brutal and reckless and yet still have lots of fun is a giant leap forward for the fates of reckless women onscreen. Valley of the Dolls (1967), based on the bestselling novel by Jacqueline Susann, is a showbiz parable in which three women trying to make it in Hollywood become addicted to pills; one kills herself, one spirals into a mess of addiction clichés, and another abandons the hustling life in favor of her New England hometown (and, presumably, marriage and family rather than a career). It’s particularly revealing that the wildest, most outgoing character, the singer Neely O’Hara (played exuberantly by Patty Duke), ends up sweaty, disheveled, and washed-up. She parties the hardest and is made to look foolish for it, yet Duke’s scenes are the most fun this movie has — she’s silly and electric and alive, and she must be stopped.

* * *

Women in movies have had their kicks, but not without consequences. When the title characters in Thelma and Louise decide to “keep going” at the end of the film — to refuse to give in to the police who finally have their car surrounded at the edge of a cliff — it’s both exultant and heartbreaking. They get their happy ending, but only metaphorically; if we read the ending literally, the women are driving to their deaths.

The stuntwomen characters in Death Proof aren’t just stand-ins for actresses on a film shoot; they’re surrogates for the female viewer who perform feats of strength and tenacity that ordinary women can only daydream of. This is why it’s so upsetting that people mistook the film for a fetishistic, misogynist screed. That it was mostly women who protested the film is particularly disappointing. After all, art, as Steiner argues, can do things reality can’t.

A decade after its release, Death Proof demonstrates that when it comes to gender violence, 2007, or even 2017, can still feel a lot like the 1970s — and in its cartoonish depiction of evil men, it gives those ordinary women license to get angry about the everlasting problem of brutality against women. Watching Death Proof, or any revenge fantasy, is a powerful act of vengeance-by-proxy — one in which everyone gets to keep their limbs.