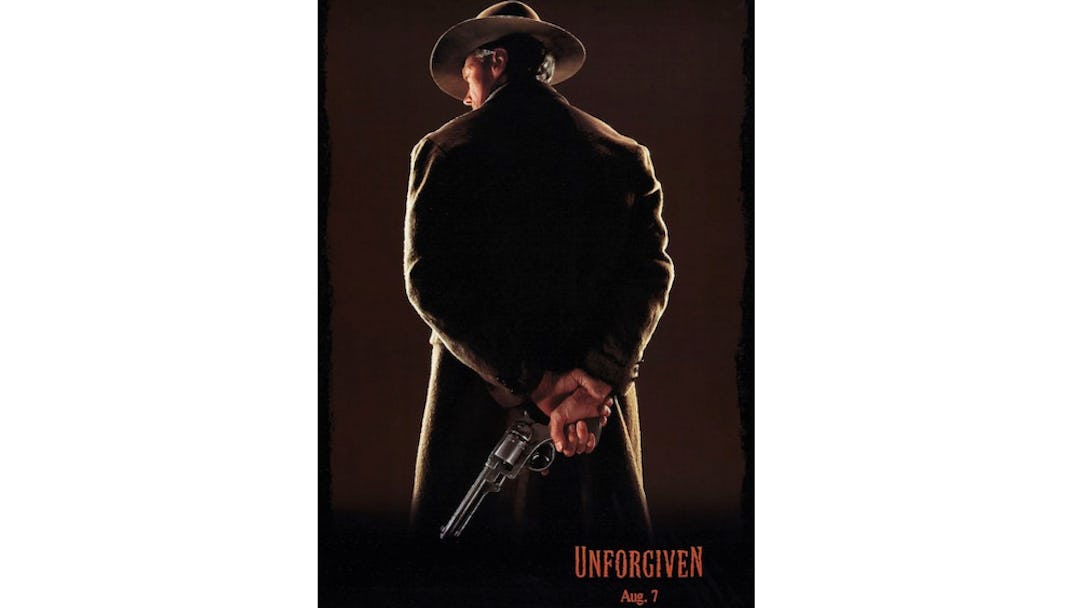

The picturesque prologue that opens Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven features a wide shot at sunset, of a silhouetted figure digging a grave – an image of dark beauty opening a movie that is decidedly not a pretty picture. Much was made, at the time of its release 25 years ago (this week) that Unforgiven was Eastwood’s farewell to the Western, a promise he’s so far kept, which must not have been easy. After all, this was an actor who’d made his name in oaters, starting with TV’s Rawhide, catapulting to international stardom via Sergio Leone’s “Man with No Name” trilogy, and chasing those films with the likes of High Plains Drifter, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Pale Rider.

All were released in an era when the traditional Western had already been “demystified,” not only by Leone but “New Hollywood” efforts like McCabe and Mrs. Miller and Little Big Man. But Unforgiven still comes on like a rude awakening, resolutely determined to show the genuine desperation and depravation of the era. And it starts right away, immediately after that gorgeous opening shot; we’re transported to the town bordello in Big Whiskey, Wyoming, where an image of grunting, businesslike sex is followed by a hard, nasty, brutal confrontation, in which two visiting ranchers beat and cut poor Delilah Fitzgerald (Anna Thomson). Right away, Eastwood is painting a picture in stark contrast to the giggly good time we typically see in Western “saloon girl” scenes. The physical brutality is compounded by the chillingly matter-of-fact negotiation that follows, in which saloon owner Skinny (Anthony James) brings in Sherriff “Little Bill” Daggett (Gene Hackman) to deal with the problem of his “investment of capital” in “property – damaged property.” (Skinny is one of the most loathsome people in Unforgiven, which is quite the accomplishment.)

Bill works out an arrangement where the thugs pay off their assault with some horses – after all, it’s no big deal, they were just “hard-workin’ boys that was foolish.” Delilah’s co-workers, led by Strawberry Alice (Frances Fisher), decide that’s not enough punishment, not by a long shot. So they pool their funds and put the word out: they’ll pay a thousand dollars to whoever will kill the men who cut up Delilah. Eventually that word gets back to Eastwood’s Will Munny, formerly one of the most feared men in the West, killer (we’re told often, in hushed tones) of women and children. He gave all that up for a good woman, the drinking and the killing and all of it; they started a family, and started a farm. “I ain’t like that anymore,” he tells the “Scofield Kid” (Jaimz Woolvet), the cocky young gunfighter who shows up one day to recruit him. The wife “scared me out of drinkin’ and wickedness.” But now she’s gone, dead of smallpox, and sloppin’ around with sick hogs ain’t much of a life either. Maybe he’ll get back in the saddle. Just this once.

It’s not that easy; he can barely even get on the horse anymore, and is such a bad shot, he has to swap out his revolver for a shotgun. For safety, he brings along his old riding partner Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman); when he shows up at their gate, Ned’s wife gives Will a sour expression, and gives Ned the same one (rather than a goodbye) when they ride off. She knows no good can come of this. And she’s right.

The trio’s real trouble isn’t the ranchers who cut the girl up – it’s Hackman’s Little Bill, a hard case who “worked them tough towns” in Kansas and Texas. Even in his first scene, when he imparts the light sentence, pains are taken to present Bill as the kind of easy-breezy type we’re used to seeing from Hackman; there’s a running bit about the house he’s building for himself, and badly, so he’s working on the roof during dialogue scenes (a clever use of physical action to open up scenes that’d normally happen in a claustrophobic jail house), or off “buildin’ his damn porch” as his deputies are getting ready for a showdown. “Maybe he’s tough,” one of them remarks, “but he sure ain’t no carpenter.” This sly touch sets him up as something of a rube – a detail that rubs up against the grinning evil that eventually reveals itself. Little Bill is a man of casual sadism, using the law to disarm Richard Harris’s “English Bob,” and then beating the shit out of the unarmed gunman as a message. (“There ain’t no whore’s gold!” he announces loudly). Hackman won an Oscar for this performance, and earned it; the speed with which he can turn his folksiness into steely menace is downright chilling.

Another effective touch is how the story of Delilah’s injuries gets grislier with each retelling, from one hired killer to the next – a commentary on storytelling and exaggeration personified by the wonderfully-named W.W. Beauchamp (Saul Rublinek), traveling with English Bob as his “biographer,” in the mold of the “print the legend” reporter in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. He notes that his books are known “to take a certain amount of liberties,” and the notion of mythologizing and hero-making is the most prevalent theme in David Webb Peoples’s screenplay. Lies are told, stories are inflated, and bad men are made heroes, at the time and especially in the years that followed; it was a nasty, ugly time, glossed over and shined up to sell dime novels and movie tickets.

And that’s the truly subversive act at the heart of Unforgiven: Clint Eastwood is puncturing a Western mythology he helped create. Much has been made of the film’s clarity around issues of violence and death – “It’s a helluva thing, killin’ a man,” Will tells the Kid, after the latter takes another life for the first time. “You take away all he’s got, and all he’s ever gonna be.” But the film is also perceptive about the way notions of masculinity are tied up in capacity for violence. When Will struggles in the first confrontation, the Kid dismisses him (“He ain’t nothin’ but a broken-down pig famer”), and when he gets himself sick along the way, sweating and shuddering in the saloon, far from the conventional portrait of the Western badass, his suffering and pain are real. He recovers enough to finish the job, to advise the kid to “take a drink,” and to wait out the whirlwind of emotions this young man is experiencing. Will’s been there; he knows. The Kid, no longer tough, comforts himself with the knowledge that his victim had it coming. Will shrugs. “We all have it comin’, kid.”

They have no idea. By this point in the story, they’ve parted company with Ned, who no longer has the stomach for killing – but on his way home, he’s caught and tortured by Little Bill and his men. (The film makes no explicit mention of Ned’s race, but Eastwood is fully aware of our discomfort during Ned’s bull-whipping by Little Bill.) As Delilah gives Will the news, he begins slowly, methodically pulling from the bottle of whiskey she’s offered. And we know that Little Bill is in it for it.

Unforgiven’s climax is both its most satisfying sequence, and its most complicated one. Eastwood shoots it in an almost crowd-pleasing style: the thunder cracks when he first cuts to Will standing in the saloon, shotgun raised, and he gets not only a hero push-in camera move, but a tough guy line. It’s the first time the film has done either. (He later promises to “come back n kill every one of you sons of bitches,” a line framed with the American flag carefully placed in the background. That’s the frontier spirit.) Eastwood proceeds to growl, shoot, and avenge his friend’s murder, embracing the very violence he – the character and the filmmaker – has spent the last two hours condemning. So the contradictions are rich: Will’s drinking again, he’s killing again, and ultimately, that means he’s broken again. But his revenge is also thrilling to watch, and, in many ways, it’s played to solicit that response. This is what we came for, and Eastwood knows it.

And maybe that’s why Unforgiven remains Eastwood’s masterpiece, and a film that feels so personal to him: because it presents such rich parallels between Will’s mission and Eastwood’s. They’re aging, hardened men, and they’ve learned a thing or two in their years riding and shooting. By the time they reach the end of this journey, both know what they must do – even while they’re aware, perhaps for the first time, of what it really means.

“Unforgiven” is now playing, in a new 4K restoration, at New York City’s Film Forum. It is also currently streaming on Netflix and HBO Go.