Genre reinvention was a cornerstone of the “New Hollywood” movement, in which free-spirited filmmakers revisited and reinvented the film genres they grew up watching. In this remarkable period, running from the late 1960s to the mid 1970s, these gifted directors changed the way we saw the Western (The Wild Bunch, McCabe and Mrs. Miller), the gangster picture (Bonnie and Clyde, The Godfather), the war movie (M*A*S*H, Apocalypse Now), the musical (Cabaret, New York, New York), the screwball comedy (Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice, What’s Up, Doc?), and the monster movie (The Exorcist, Halloween).

Yet no genre reinvention was as plentiful, or provided as many fascinating counterpoints, as that of the private eye mystery/thriller. In my new book It’s Okay With Me: Hollywood, The 1970s, and the Return of the Private Eye , I analyze the key detective movies of the period (including Chinatown, The Long Goodbye, Klute, Shaft), and some of the lesser-known entries as well (Black Eye, Marlowe, The Big Fix, Sheba Baby), to understand why this genre spoke so directly to the cultural and political moment.

In this excerpt, I break down Arthur Penn’s Night Moves, starring Gene Hackman (currently streaming on FilmStruck).

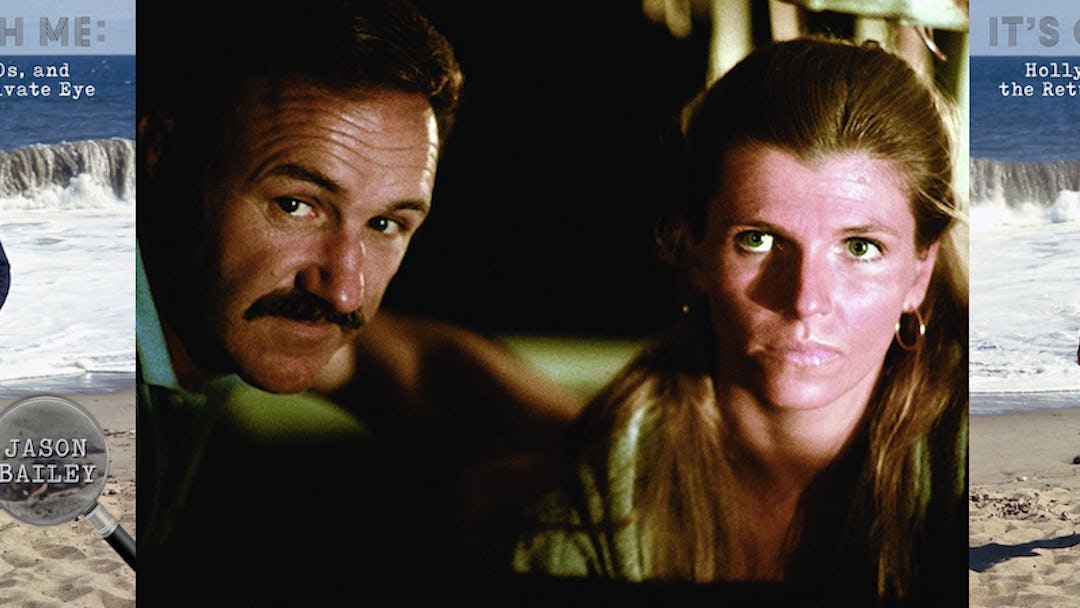

(‘Night Moves,’ Warner Brothers)

From Chapter 4: “Pessimists”

Arthur Penn’s Night Moves came out in 1975, the year after Chinatown, and comparisons were immediate and ongoing. Mean Streets and Raging Bulls author Richard Martin separates them most convincingly: “Lacking… the nostalgic qualities of Chinatown’s period setting, the vision of American society offered in Night Moves is, if anything, bleaker than Chinatown’s because it is manifestly closer to the experiences of the contemporary viewer.” In other words, there were no pretty pictures and vintage cars to distract us from the ugliness at this story’s center.

Penn confirmed as much. “It was the period after all those assassinations, you know?” he said. “That depleted one’s optimism: the ability to feel that tomorrow is going to be better was definitely gone. I thought that’s what this movie is about. Then also, I thought, gee, detective films have always been so clever, the detective always figured it out at the end. What happens if he himself is psychologically blocked in an area that keeps him from being able to perceive what the central event is all about?”

Penn seems to begin by coloring inside the lines. Harry Moseby (Gene Hackman) works out of a cluttered office with blinds on the window and “MOSEBY CONFIDENTIAL” stenciled on the office door; he’s got a giant Rockford Files-style answering machine, and the funky opening music isn’t far removed from that television series either. He’s given a standard job tracking down a teenage girl; the case is “one of Nick’s handouts,” but he steadfastly refuses to work at Nick’s agency (“I’d go bananas there within a week”).

Yet before he can dig into the case, he discovers his own wife (Susan Clark) is stepping out on him. Paid to shadow deceitful wives and cheating husbands, the investigator is himself a chump. Penn and screenwriter Alan Sharp turn a structural norm on its head; rather than giving us the conventional pair of seemingly unrelated cases that unexpectedly intersect, Harry Moseby encounters personal woes that he cannot separate from his professional life. The Other Man’s encouragement to “c’mon, take a swing at me Harry, the way Sam Spade would” underscores the divergence in their experience; whatever his woes, Sam Spade never had to deal with a broken marriage.

But as much as he may fashion himself after Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe, Harry Moseby lacks their aloofness. Night Moves is, according to Robert Kolker, a “desolation film,” in which “Gene Hackman’s Harry Moseby is a figure of contemporary anxiety, with none of the wit and bluff that Bogart brought to his roles, none of the security in self-preservation – indeed, none of the sense of self and its endurance that allowed the forties’ detective to survive.” He’s often uncertain of his world and how to move through it; when he stumbles into the fuzzy Florida Keys triangle between baby-doll Delilah, her former stepfather Tom (John Crawford), and Paula (Jennifer Warren) he doesn’t know how to react. The old-fashioned query he poses – “D’you mind if I ask what the set-up is? Are you with Tom?” – pegs him as a resident of Squaresville, for better or worse. Throughout the film, he’s surrounded by failed marriage, divorce, adultery, promiscuity, and even incest, and while his morality may be out of step with the sexual freedom around him, he also seems the only man in the film who doesn’t sexualize “Deli”; he sees her as a child, an inclination clarified by his retort to Tom’s chuckling confession that there “outta be a law” (“There is,” Harry replies).

He’s a man who ultimately does as he’s supposed to; in their first meeting, Arlene asks if he’s “the kind of detective who, once you get on a case, nothing can get you off it,” and of course, he ends up being exactly that kind of detective. He chases down Quentin and flies back down to Florida on his own dime when he’s no longer working for anyone – in fact, when he no longer even has an agency. But if he acts as a detective is expected to act, he does so in a decidedly modern way, leaning in hard on the character’s vulnerability. He confronts his wife’s lover with his chest out, full of tough-guy bravado, but he crumbles when he asks of their affair, “How serious is it?” Long-held notions of machismo and sensitivity were in flux in the 1970s; in magazine articles and self-help books (to say nothing of therapy sessions and couples counseling), men were being told to display and express previously bottled emotions, and aging Harry is still trying desperately to feel nothing. “I can’t hear myself think!” his wife screams. “Lucky you,” he mumbles.

Harry’s emotional struggles, and the perceptions of weakness it betrayed, colored some of the less enlightened reviews. Variety dubbed it “a suspenseless suspenser,” while the New York Times’ Vincent Canby called it “an elegant conundrum, a private-eye film that has its full share of duplicity, violence, and bizarre revelation, but whose mind keeps straying from questions of pure narrative to those of the hero’s psyche.” This is a bad thing? (After Penn’s death, the Times was kinder; Manhola Dargis called Night Moves “great” and “despairing,” praising Hackman’s turn as “a private detective who ends up circling the abyss, a no-exit comment on the post-1968, post-Watergate times.”)

The film’s critics apparently longed for a formula whodunit, blind to the existential despair that made it so much more than just another detective picture. Or maybe it was too much; Kolker writes, “Night Moves takes a major element of modernism, its bleakness and desolation, its conviction that failure and isolation are the only ends available to a male character, as far as anyone wished them to go.” By this point in the mid-1970s, artists could no longer pretend that the cultural revolutions of the late 1960s were more than just a passing fancy; now they would regard them as a near-miss, and look back not on their shared triumphs, but shared traumas. Before their sexual coupling – an encounter Harry allows himself as payback for his wife’s affair, and which Paula is using as a deceitful diversion – they discuss the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, which is quite the mood-setter.

“It’s one of those questions everybody always knows the answer to,” Paula explains, recalling how “the newsreels, they made it look like everything was happening underwater,” so slow and distant. That motif of underwater death recurs throughout the film: Deli’s discovery of the sunken airplane, the pilot inside chewed on by fish, Paula’s blood in the water in the climax, Harry watching his old pal Joey Ziegler drown through the boat’s glass bottom.

Audiences that summer of ’75 steered clear of Night Moves to watch another chronicle of underwater death: Jaws, which lay waste to all competition and shifted the course of ‘70s cinema (and all decades thereafter) into a mode of blockbuster saturation. In contrast to Night Moves, its threat was external, and its heroes could beat it; once it’s defeated, they share a joke and paddle off into the sunset. Night Moves, on the other hand, closes with our hero’s bloody fist pounding a cheap, plastic boat seat cushion, cursing himself.

“It’s Okay With Me: Hollywood, The 1970s, and the Return of the Private Eye” is available now in paperback and ebook, and via Kindle Unlimited.