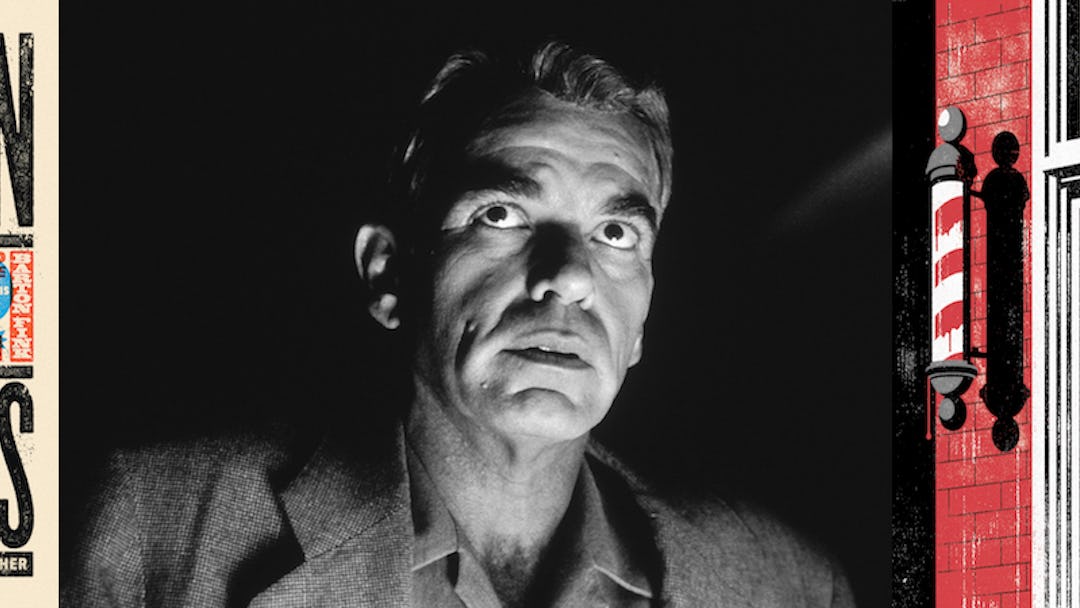

One of the pleasures of the big, handsome, mid-to-late career monographs that Abrams Books has made a specialty (they also released books on Wes Anderson, Oliver Stone, and Martin Scorsese) is that they allow us to appreciate the “minor” entries of those oeuvres. Take, for example, Adam Nayman’s The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together (out tomorrow), which, yes, gives full analysis and appreciation to Fargo, Raising Arizona, The Big Lebowski, and No Country For Old Men. But Nayman also has plenty to say about supposedly secondary works like The Hudsucker Proxy, Burn After Reading, and, in this excerpt, the all-but-forgotten 2001 black-and-white film noir riff, The Man Who Wasn’t There.

The things that Ed wants—a fulfilling job, an attractive partner, a prosperous family life— mark him as a very conventional man, and yet The Man Who Wasn’t There draws much of its power from how rigorously it interrogates the idea of its protagonist’s normality. Or rather, if Ed Crane is Everyman, then it’s frightening to consider the welter of resentment, fear, and denial binding together the social fabric. One of the running motifs in the movie is that of concealment. Nearly all the major characters are hiding something that would reverse other people’s impressions of them in an instant, beginning with Creighton’s bald pate, which extends also to his (barely) closeted homosexuality. Doris’s secrets are myriad; her a air with her boss, Big Dave, is one, and her pregnancy by him, which is only discovered after she commits suicide in police custody (cutting off the film’s apparent transformation into a courtroom drama), is another. James Gandolfini’s Big Dave represents himself as a war hero but actually sat the conflict out at home. Like the Big Lebowski, he’s a superficially powerful man propped up by a wealthy woman—his department store, Nirdlinger’s, bears her family’s surname. Meanwhile, Dave’s wife, Ann Nerdlinger (Katherine Borowitz), maintains a facade as a doting, dutiful wife but, as is revealed during a midnight visit to Ed’s house after the death of her husband (a crime pinned on Doris, but for which Ed is responsible), is a deeply paranoid woman who harbors elaborate sexual fantasies involving beings from another world. Ed’s confrontation with Ann may seem like an extraneous digression in a movie that is otherwise extremely tight, but it’s actually the film’s secret heart. The Man Who Wasn’t There is set in 1949, two years after the supposed UFO crash in Roswell, New Mexico, that became ground zero for legions of conspiracy theorists. (Northern California was also the setting for Jack Finney’s 1955 novel The Body Snatchers, a signal text that satirized the creeping conformity of the Eisenhower era.) The Coens audaciously integrate the themes and iconography of mid- century science fiction into their noir narrative. Ann’s story about being abducted and probed, along with Big Dave, during a camping trip is her coping mechanism for the fact that their romance had long since waned (“He never touched me again”), a lack of sexual activity that mirrors Ed and Doris’s. In conflating her own sexual disappointment with this larger cultural undercurrent, Ann reveals herself as the product of a schizophrenic zeitgeist. She’s simultaneously obsessed with and terrified by the large-scale social and technological change around her. As staged by the Coens and Deakins, who emphasize the black dots of her funeral veil (a reference to “dottiness,” perhaps), Ann’s visit plays out as a comic torment to Ed, who is dealing with much bigger problems in the form of his wife’s murder charge and his unspoken guilt over the fact that he’s the one who did the deed. It’s also a chilling moment of recognition. Like Ann, Ed wants nothing so much as to rationalize the failure of his marriage and to account for his alienation, even if he stops short of invoking actual aliens in the process. But his patronizing, empathetic response to Ann is also telling. Much later in the film, after he’s been arrested for a murder he didn’t commit (that of Creighton Tolliver, who was actually beaten to death by Big Dave after Dave discovered his scheme), Ed imagines himself encountering the very same UFO, which hovers above the prison before flying o toward the horizon, leaving him as bereft and alone as Ann Nirdlinger. As The Man Who Wasn’t There goes on, Ed begins to believe that he can see through the people around him, even as his own motives are utterly transparent. In this, he resembles the perceptive but self-deluding hero of Albert Camus’s existentialist classic novel L’Étranger(1942), which critic Richard Gaughran persuasively locates as the film’s true artistic inspiration, more than the noirs evoked by Deakins’s cinematography and the script’s numerous references to the novels of James M. Cain (not only in the playful use of “Nirdlinger,” but also in allusions to the plots of Mildred Pierce [1941] and The Postman Always Rings Twice [1946]). Like Camus’s Meursault, Ed narrates his tale from prison; both men have a fatalistic view on life that gets confirmed by the savage but seemingly unpremeditated murders that they commit. In fact, quite disturbingly, it is killing Big Dave—and getting away with it—that makes Ed feel, for the first time, like he is not a dupe but a kind of visionary. “It seemed . . . like I had made it to the outside, somehow, and they were all struggling down below.” Ed’s emerging self-knowledge does him little good when he’s at the mercy of fate, however. The plot of The Man Who Wasn’t There is organized around long, crisscrossing streaks of deceptively good and definitively bad luck. Ed is bypassed as a suspect for Big Dave’s murder but has to sit silently as his wife takes the rap; Freddy Riedenschneider’s “uncertainty defense” sounds persuasive but becomes a moot point after Doris’s suicide; Ed survives a car crash only to awaken in police custody for a murder he didn’t commit. Where in The Hudsucker Proxy, Norville Barnes is only “fortune’s fool” until the powers that be smile upon him, Ed Crane has nobody looking out for him. This cosmic absence is played up in an early scene of him and Doris attending their local church: A slow pan down from the stained-glass ceiling to the pulpit reveals not a priest but a bingo caller in an exquisite visual pun, locating a facile game of chance in a space traditionally associated with divine certainty. In contrast to the Old Testament–inflected worlds of A Serious Man, True Grit, and Hail, Caesar!, The Man Who Wasn’t There pretty clearly unfolds in a godless universe (the title could even be taken as a riff on this same absence).

The Coen Brothers: This Book Really Ties the Films Together is out tomorrow; read more about it here, and order it here.