This was a splendid year for books that took the political into the personal realm and vice-versa — and that makes sense, because in 2018 America, as in previous years, there was no escaping politics. My own reading was somewhat less wide-ranging than it has been in years past, because I spent a possibly inordinate amount of time reading books about motherhood for an essay, but I also stuck to the subject because it was exciting to find my own right now experience as a new-ish mother getting serious literary treatment from so many corners at once, so take that as a caveat and disclosure. (Note to publishers: we still need more literature and advice books about queer and gender-nonconforming parents.)

Other mini-trends of 2018: books about women’s anger (both at their personal lot and at sexism at large), books re-engaging with ancient mythology, and in the year we lost Philip Roth, sly and thoughtful female-penned reappraisals of Great Literary Men.

(Mariner Books)

How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, Alexander Chee

From hanging out in San Francisco at the beginning of the AIDS years to catering for William F. Buckley, Jr. and far beyond into painful, strange and beautiful corners of the country’s recent history, Alexander Chee has lived a disarmingly full life. His essays veer between straight memoir and craft and writing-life rumination, a perfect mix. I’ve been browsing through each installment one by one, out of order, for months now —approaching the pieces about novel-writing with a mix of rabid hunger for wisdom and fear that they will reveal my own shortcomings as a writer. I shouldn’t be scared: Chee’s thoughtful, self-aware candor pervades each piece, all of which are threaded together by a deep, but never grandiose, faith in storytelling.

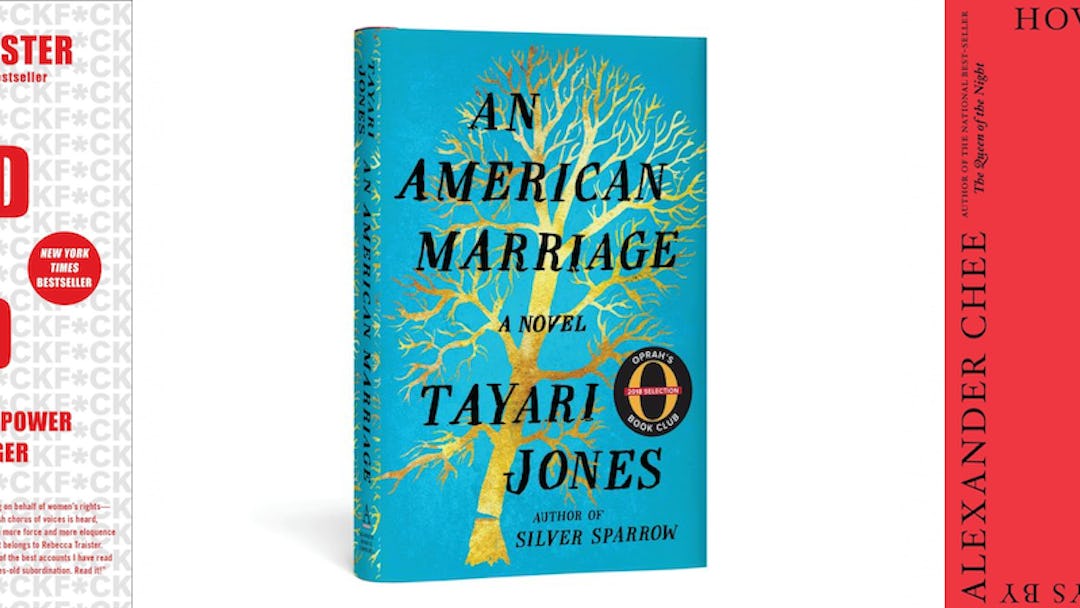

(Algonquin Books)

An American Marriage, Tayari Jones

Tayari Jones is a master of hooking readers from premise to execution to depth. Her latest novel details the excruciating toll that America’s racist plague of mass incarceration takes on individual lives; specifically, she examines how an imprisonment on false charges affects a loving match which begins in hope. But don’t let the term “excruciating” deter you, as none other but Oprah wrote, before selecting the book for her club: “After the first few chapters, as I got to know Roy and Celestial and Andre, I forgot they were fictional characters. I found myself in that zone readers yearn for: I wanted to cancel all my plans and curl up with my new friends.”

(Henry Holt and Co.)

In my own third year of motherhood, this book about choosing not to be a mother shook me the most profoundly of anything I read. At times reading more like a meditation than an novel, Motherhood may have obscured its arc, but it was always there, quietly cathartic. I respect Heti deeply for choosing to push the form of “novel” to new limits, and refusing to be bound by cliched demands for “sympathetic protagonist” and “high stakes” while giving us both of those elements in sneaky ways; her narrator (a stand-in for herself) is so fiercely committed to her writing that she isn’t sure she can be a parent. She questions why women are punished for their reproductive choices and offers bite-size feminist wisdom in abundance here. But Motherhood is grander than one woman’s specific dilemma: who can’t relate to getting older and seeing doors shut — professional, personal, even emotional — and saying farewell to the you that might have been?

(Little, Brown and Company)

And Now We Have Everything, Meaghan O’Connell

O’Connell, veteran of the Billfold and The Cut, brings her funny, frank, blog-honed style to this memoir of a rather-unexpected pregnancy, a memorably difficult labor, and a single year of parenthood. Hers is a book that I would give to everyone whose spouse, close friend, or parent is contemplating having a first child, or maybe who had one already; what a gift to be able to make people who have recently lived through an experience see it more clearly. Pair this book with Angela Garbes’ essay collection, Like a Mother, which combines cultural and scientific critique with personal reflection and offers a much-needed critique of white constructions of motherhood.

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Rachel Cusk is on a completely different level, offering all of Jane Austen’s wit with none of her warmth, and we’re all just along for the ride. Kudos concludes a trilogy that began with the groundbreaking Outline; in each of her books, her narrator, seemingly dispassionately, reports on conversations she has, or, more accurately, receives, with only an occasional rejoinder of her own. But beneath the cold, tight, style is a deep anger, and the entire trilogy becomes a commentary on female stoicism, self-denial, and repressed fury. This last book travels to a variety of literary conferences and provides Cusk’s narrator an opportunity to subtly, yet completely viciously, skewer the literary world, journalists, and finally, men.

(Simon & Schuster)

If Cusk takes down literary world, Lisa Halliday’s unique book, in three parts, feels like a defense of “important” writers and their work. A final, slyly clever, section connects the first two, which are, respectively, a chronicle of a May-December affair involving a great writer modeled on the late Philip Roth — and a compressed novel about the Iraq war and post 9/11 Islamophobia, taking place in a holding room at Heathrow Airport. The details that remind the reader of life in Baghdad before the war ravaged the city are gutting; the final twist is the definition of thought-provoking, gently sending a salvo into the “who can write whose stories” debates that constantly rage online. For fun, pair Asymmetry with The Friend, Sigrid Nunez’s National Book Award-winning novel about a woman’s grief after another great, womanizing male writer, her mentor, passes away.

(MCD)

The Golden State, Lydia Kiesling

It’s so rare to read a novel that actually puts a young child on the page with no sentimentality and lots of realism, but this novel does it; babbling Honey, who accompanies her temporarily-single mom on a flight from daily life that’s half adventure, half nervous breakdown, demands to be fed, changed, napped, awoken, kissed, and bandaged throughout the pages of the book. Kiesling’s novel-feeling commitment to capturing the realities of daily childcare, combined with keen-eyed looks at secessionism in a remote area Northern California and the way families can get snarled in the bureaucracy (and Islamophobia) of immigration authorities, earns it a spot on this list.

(W. W. Norton & Company)

The Odyssey, Homer, translated by Emily Wilson

Emily Wilson’s shining new translation of the great Homeric epic with a feminist sensibility garnered universal acclaim and wowed the classics world. Pair this one with Madeline Miller’s bestselling Circe, a somewhat less serious but very fun feminist reimagining of the Odyssey’s island enchantress and her life.

(Riverhead Books)

I am a hard sucker for any novel or film that takes music and musicians as its main subject, so naturally I snatched up The Ensemble. Gabel’s debut is a gentle portrait of four members of a string quartet over the decades they play together, fall in love, fight, reconcile, and make music, becoming more than the sum of their parts offstage as well as on. I can still close my eyes and picture some of the novel’s magnificent concert scenes, and imagine the feelings of the players as they walk onstage.

(Simon & Schuster)

Good and Mad, Rebecca Traister

Reading Good and Mad as a polemical book, I wished Traister had addressed the material conditions of contemporary women’s lives more. Much of her thesis about women’s anger relies on the daily frustrations women encounter in their interactions with men, which at least to me, felt well-trodden and a little essentialist.

But the book nonetheless shines as a document of this crucial moment in feminist and female-led activism — from the pussy hats to Black Lives Matter to #MeToo — surveying the way the 2016 election shook up feminist thought while activists’ reactions to the election built on decades of organizing. Her critique of white women’s proximity to patriarchy is necessary, and the book in total is a lively, well-written, and thorough work of living history that I have no doubt people will be turning to for a long time to ask what the hell happened between 2016 and the 2018 midterms. I especially appreciated semi-historical sections on figures like Shirley Chisholm and Andrea Dworkin, whose approaches to anger were ahead of their era, but might have felt very at home in 2018.

Note: Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her and Brittney Cooper’s Eloquent Rage have been linked with Traister’s book all year and I’m repeating the somewhat obvious and flattening move by including them here, but they have very different and important takes on the subject of anger to offer readers, and are worthy companions, or on their own.

Don’t Miss These, Either:

Disoriental, a story of Iranian memory and diaspora by Négar Djavadi, (translated by Tina Kover; Heavy, Kiese Laymon’s memoir of race, weight and family; Robin MacArthur’s Vermont family chronicle Heart Spring Mountain; Nicole Soojung’s stunning adoption memoir All You Can Ever Know; Rachel Lyons’ provocative story of a boy’s death and an artist’s birth, Self-Portrait with Boy; Ling Ma’s devastating office satire in a zombie apocalypse, Severance; Sharp, Michelle Dean’s primer on 20th Century female intellectuals; Hermione Hoby’s New York heatwave novel Neon in Daylight, and Anjali Sachdeva’s mind-boggling original collection of stories, All The Names They Used for God (seriously, read this one).