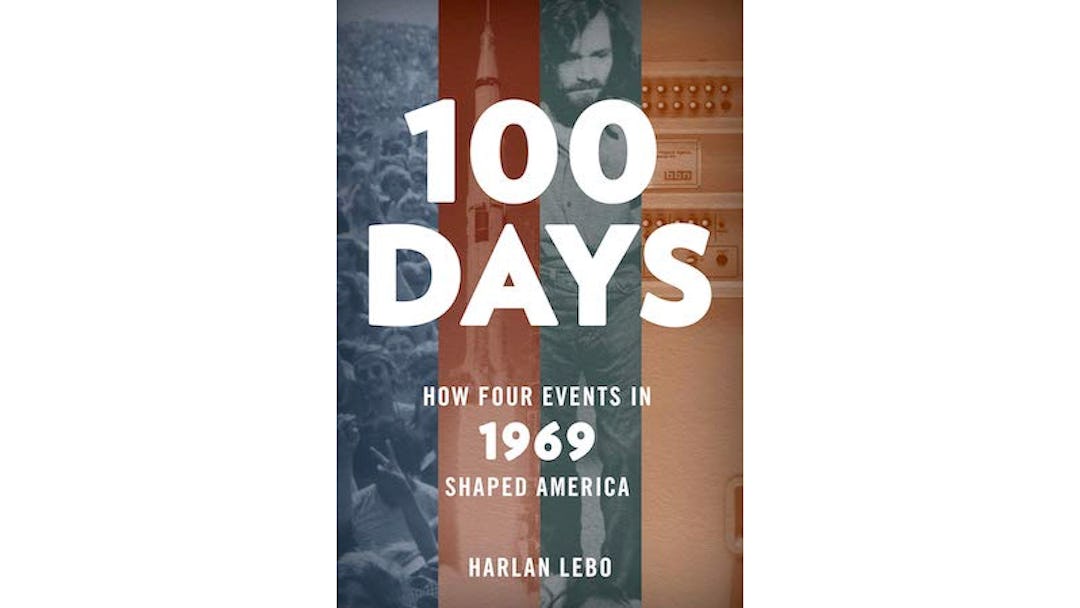

You can barely turn on a television or click a link these days without hearing about how revolutionary 1969 was during this 50th anniversary year. But what exactly made that particularly year so vital, important, and influential? Historian Harlan Lebo attempts to answer that question in his new book 100 Days: How Four Events in 1969 Shaped America (out now from Rowman & Littlefield Publishers), which deep-dives into four specific occurrences – the Apollo 11 moon landing, the Manson Family murders, the Woodstock music festival, and the birth of what would become the Internet – detailing how they came to pass and their cultural reverberations, to better understand this pivotal moment in our history.

To commemorate this week’s anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing, we’re proud to present this excerpt, which delves into the complicated history of that mission, the culmination of the moon shot announced by President Kennedy at the beginning for the decade.

FROM "100 DAYS: HOW FOUR EVENTS IN 1969 SHAPED AMERICA"

Kennedy was so thorough in creating his vision of the lunar program as an American objective that it is often forgotten that on two occasions he was willing to give up competition with the Soviets and partner with them in a cooperative space mission, inviting Khrushchev to unite in a joint moon effort. At the summit meeting between the two leaders in June 1961, Kennedy offered, “why don’t we do it together?” At first Khrushchev seemed interested, but on the second day of the conference, he declined, saying that a disarmament agreement had priority over creating a partnership for space.

More than two years later, this time in a speech on September 20, 1963 to the general assembly of the United Nations, Kennedy again suggested a partnership in a joint expedition to the moon.

“Why should man’s first flight to the moon be a matter of national competition?” asked Kennedy. “Surely we should explore whether the scientists and astronauts of our two countries – indeed of all the world – cannot work together in the conquest of space, sending some day in this decade to the moon not the representatives of a single nation, but the representatives of all of our countries.”

The idealistic Kennedy, said John Logsdon, founder of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, “never gave up that hope even as he approved the peaceful mobilization of the substantial human and financial resources needed to meet the lunar landing goal he had proposed.”

However, the idea of a joint U.S.-Soviet space mission faded away after Kennedy was assassinated – yet another question mark in the President’s legacy about an visionary project that might have been.

Two months after the Rice Speech, Kennedy’s uncertainty about the space program would become clear in a November 21, 1962 meeting in the cabinet room with Webb, presidential science advisor Jerome Wiesner, budget director David Bell, and other aides.

The meeting, which was tape recorded, began as a review of budget priorities for the space program, but soon evolved into a philosophical discussion – often heated – about the priorities and direction of the space program.

President Kennedy: Do you think this program is the top-priority program of the Agency?

James Webb: No, sir, I do not. I think it is one of the top-priority programs, but I think it’s very important to recognize…[that] several scientific disciplines that are the very powerful …converge on this area.

Kennedy: Jim, I think it is the top priority. I think we ought to have that very clear. Some of these other programs can slip six months, or nine months, and nothing strategic is gonna happen... But this is important for political reasons – international political reasons. This is, whether we like it or not, in a sense a race. If we get second to the moon, it’s nice, but it’s like being second any time. So that if we’re second by six months, because we didn’t give it the kind of priority, then of course that would be very serious. So I think we have to take the view that this is the top priority with us.

Everything that we do ought to really be tied into getting onto the moon ahead of the Russians.

Webb: Why can’t it be tied to preeminence in space–

Kennedy: Because, by God, we’ve been telling everybody we’re preeminent in space for five years and nobody believes it… I do think we ought get it really clear that…this is the top-priority program of the Agency, and one of the two things, except for defense, the top priority of the United States government.

Now, this may not change anything about that schedule, but at least we ought to be clear, otherwise we shouldn’t be spending this kind of money because I’m not that interested in space. I think it’s good; I think we ought to know about it; we’re ready to spend reasonable amounts of money. But we’re talking about these fantastic expenditures which wreck our budget and all these other domestic programs, and the only justification for it … to do it in this time or fashion, is because we hope to beat them and demonstrate that starting behind, as we did by a couple years, by God, we passed them.

After a little more back and forth, Kennedy excused himself and left the Cabinet Room, but the others remained for a discussion that revealed Webb’s own concerns about the management and direction of NASA.

Webb: Now, now let me make one thing very, very clear. The real success of this program and what it does for this administration in terms of prestige and for the country in terms of a position of preeminence is going to depend not so much on these target dates, but how this program is run.

Bell: I don’t think that the President or any of us has any illusions about that. We all think it’s being run very well.

James Webb: Well, it’s not being run too well!

David Bell: You’re improving it every day.

James Webb: We’re running fast and trying to stay ahead.

David Bell: But…none of this should be interpreted as a challenge to the basic management.

James Webb: All I’m trying to say is, Dave, that we are running about three steps ahead of a pack of hounds. And we have got some real vulnerabilities to validate the capacity to do this thing which is almost beyond the possible anyhow.

David Bell: That’s perfectly clear. But our problem is that we all work for the President and as far as he’s concerned, as he very clearly expressed this morning … the manned lunar landing program is the number one-priority program.

James Webb: I fought tooth and toenail here to avoid this implication that … we are just a one-purpose Agency going to the moon. And I hate to see that….

Nine days later, Webb complied with Kennedy’s request by sending a detailed letter that described NASA’s priorities – with the moon program, of course, being number one – but with a strong endorsement that the rest of NASA’s agenda was not only important to establishing the U.S. program as “preeminent in space,” but also included key programs that would affect the success of a lunar landing, including among many others, research on crew safety, guidance, and topography.

Webb’s letter convinced Kennedy. The moon program would continue as scheduled, with no additional push for an earlier date.

“Ultimately, Kennedy agreed with Webb on all of his major points,” said historian Dwayne Day. “By the summer of 1963, he also publicly agreed that America sought to become preeminent in all important aspects of the space program.”

But Kennedy would never see the broad benefits that would come to the nation as a result of a full-fledged lunar program – that by advocating spending on space, he was creating a new infrastructure for technology inventiveness and increased support for education that would strengthen the nation’s place in the world, perhaps even more effectively and with longer effects than the lunar program itself could sustain.

“Kennedy’s reasons for America going into space were entirely based on the need to protect America’s national security interests,” said Dallek. “He had little interest in space for its scientific value – although he certainly understood why others felt strongly about this – but he didn’t consider a strong connection between the space program and long-term benefits for the country, other than the jobs it would create. He saw the science that was gathered only as a benefit to speed the moon program along.

“The one who saw it was Lyndon Johnson,” said Dallek, “because Johnson could see how the space program would create intellectual and economic benefits that would open a new era for the American economy. But at the moment, Kennedy was opening the door, giving Americans a sense of beginning to become a new progressive nation, especially in terms of technology. This perception would become enormously important to the nation.”

But was it all worth it? Critics of the space program asked – with plenty of justification given the number of domestic priorities in need – why should America spend billions on space, just to beat the Soviets to the moon, as a tool to impress other nations of America primary position on the planet? And others would ask: why not spend the same money on foreign aid?

It’s true that the objectives of the space program might have been handled by venturing down other paths – such as huge increases in foreign aid – but those avenues were no guarantee of success either, and writing checks all over the world would not have created a unifying national goal and knowledge-building at home.

Kennedy’s misgivings about the budget for space no doubt continued for the rest of his short life. But he also recognized the undeniable realities of working with the legislative branch of government on money matters: one of the hard facts of Congressional dealings is gaining the momentum needed for multi-billion-dollar commitments of federal dollars to cover years of funding for new programs that do not directly involve war or urgent national security.

As the National Defense Education Act in 1959 demonstrated, even improving education for millions of young Americans – a seemingly-obvious priority – had been politically impossible until defense became part of the issue. For the new President to go to Congress and ask for billions to change the world would have been politically unfeasible.

“I partly agree with those who said these enormous financial resources – tens of billions of dollars in 1960s currency before it was over – may have been better devoted to combating our own planet’s ills and helping our own country’s poor,” said Sorensen, even though he had led the group that encouraged Kennedy to propose the lunar mission.

But, Sorensen also said, “I do not believe for a moment that those billions would have been approved by Congress for compassionate purposes, nor do I believe that Congress would have voted for the many less dramatic science programs proposed as alternatives by many scientists. The moon shot was the making of America’s superiority in space, and all the scientific, diplomatic, and national security benefits that followed.”

From “100 Days: How Four Events in 1969 Shaped America,” by Harlan Lebo, out now from Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. All rights reserved.