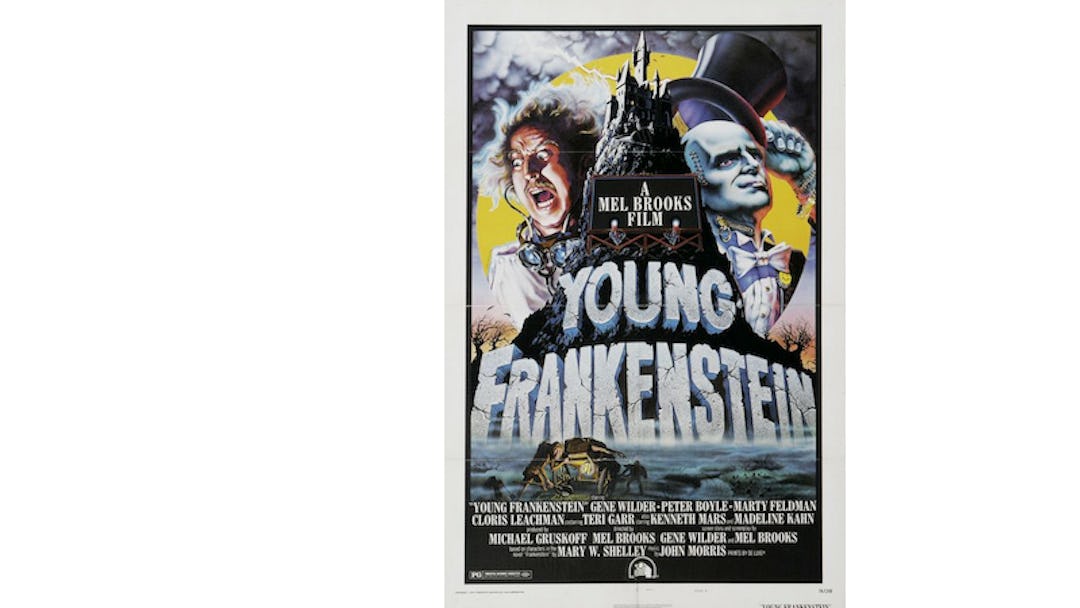

The familiar 20th Century Fox logo and fanfare begins the film — but in black and white, segueing into a dramatic orchestral theme and a title that hits with a bolt of lightning and a crack of thunder, in front of the moody image of an ornate castle on a distant hilltop. With those familiar images, audiences were welcomed to Young Frankenstein, Mel Brooks’ affectionate parody of the Universal horror masterpieces. The movie, which is out on Blu-ray today in a new anniversary special edition, hit theaters 40 years ago — in the same calendar year as his equally successful Blazing Saddles , a one-two punch that’s all but unprecedented among comedy filmmakers. Yet for all of Saddles’ influence, Frankenstein may be even more beloved, for its place within both the filmography of Brooks and the surprisingly venerable cross-genre of horror comedy.

The combination has been around a long while — dating clear back to silent pictures like Harold Lloyd’s Haunted Spooks and Wallace Reid’s The Ghost Breaker. But the real table-setter, in terms of the horror comedy’s style and appeal, was the 1948 smash Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. It was a bit of a double Hail Mary at the time for Universal — the comedy team of Bud Abbott and Lou Costello had seen slowly but steadily decreasing box office, as had the Universal monsters. By fusing the two franchises, and the two genres, the studio managed to revitalize both (at least for a time).

But what’s interesting and instructive about A&C Meet Frankenstein is that it is a genuine merging of those two sensibilities, as opposed to an all-out parody of the monster movie. It’s not a serious film, as no Abbott & Costello picture can be, yet it takes its monsters seriously. But don’t take it from me; here’s one of the picture’s biggest fans, on its genius: “The Abbott and Costello stuff was funny, but when they were out of the room and monsters would come on, they’d kill people! When was the last time you saw anybody in a horror-comedy actually kill somebody? You didn’t see that. I took it in, seeing that movie.” That fan is Quentin Tarantino, who would take its lessons on tonal shifts and the interspersing of comedy and gore to heart.

Young Frankenstein operates in much of the same spirit. Unlike some of his other works (like Saddles, Spaceballs, or the later, and far less successful, Dracula: Dead and Loving It), the Brooks of Young Frankenstein isn’t really skewering the conventions of the horror movie — he’s paying tribute to them, and using them as scaffolding for his particular brand of goofy, Borscht Belt burlesque. When it comes to his ostensible target, the key is the notion of “affectionate parody.” He seems to genuinely love these old movies, and takes joy in appropriating their look and feel, from the evocative black and white photography to the Gothic settings to even the original Frankenstein laboratory equipment, for which designer Kenneth Strickfaden is thanked with prominent placement in the opening credits.

And this, I think, is the key to the popularity of the great horror comedies that have followed those two classics. Horror fans are a touchy lot, and don’t care for movies that tell them what they love is stupid. So the truly successful horror/comedies of the past 40 years — films like An American Werewolf in London, Evil Dead 2, Shaun of the Dead, The Cabin in the Woods, Scream, Gremlins, Ghostbusters, and so on — have merged those two sensibilities, rather than sacrificing one for the other. Laughter and fear are two of the most visceral reactions we can have to events on a movie screen — and are, handily enough, the two most enjoyable in a darkened theater, full of strangers. So when a film can do both simultaneously, watch out; it’s a potent, long-lasting brew.