As we’ve mentioned, this weekend marks the 40th anniversary of the release of Jaws, Steven Spielberg’s masterful adaptation of Peter Benchley’s bestseller. By this date, the conventional wisdom that Jaws was a cinematic game-changer has taken hold — but like many such pronouncements, those who make it aren’t always clear on the details. In fact, it’s a little bit complicated, because Spielberg’s smash changed the way Hollywood did business in a variety of ways, both for good and ill.

B-Movies Became A-Movies

The film’s difficult production has become part of its legend: Jaws went over budget and over schedule, thanks in no small part to Spielberg’s insistence on shooting on the water instead of in a tank (per studio norms), and the comically unreliable sharks that were built for the production. Those no-shows caused Spielberg to rethink the movie on the fly — to its benefit. “The effects didn’t work, so I had to think fast and make a movie that didn’t rely on the effects to tell the story,” he told Easy Riders, Raging Bulls author Peter Biskind. “I threw out most of my storyboards and just suggested the shark. My movie went from William Castle to Alfred Hitchcock.”

As a result, what was, in many ways, a drive-in-style monster movie became something more — and ended up putting the drive-in supply line out of business. In a 2010 Speakeasy interview, “King of the Bs” Roger Corman, producer of countless low-budget monster and sci-fi flicks, recalled, “Vincent Canby wrote in the New York Times: ‘What is Jaws but a big-budget Roger Corman film?’ What he didn’t say was it was not only bigger but better. I’m perfectly willing to admit that. When I saw Jaws, I thought, I’ve made this picture. First picture I ever made was Monster From the Ocean Floor. This is the first time a major had gone into the type of picture that was bread-and-butter for me and the other independents. Shortly thereafter, Star Wars did the same thing. They took away a lot of the backbone of the picture we were making.” Instead, Corman and his ilk ended up chasing the majors, turning out imitation/parodies of the big hits, such as the Jaws riff Piranha and the Star Wars-inspired Battle Beyond the Stars.

Spielberg Became Spielberg

Producers David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck were taking a real risk when they hired Spielberg — after all, this was a high-profile adaptation of a very big book, and at the time, he only had one theatrical feature to his name ( The Sugarland Express ), which hadn’t exactly taken the world by storm. But his low-budget man vs. machine TV movie Duel had convinced them he could pull off Jaws, and he proved them very, very right. Had the movie tanked, or had they not taken that chance in the first place, we might’ve seen a very different career for Mr. Spielberg; in a 1976 Playboy interview, Robert Altman noted, “I think Steven Spielberg will endure, though it’s tough when a picture like Jaws brings you a lot of success and money overnight that may not strictly be related to the merit of your work. I am not knocking Jaws, which was a magnificent accomplishment for a kid that age. But will he now be able to go off and make a small personal film?” The answer to Altman’s question was probably another one: “Does he want to?” He would eventually make a few such films, but for the most part, he seemed content to become the biggest director in the business.

Summer Movies Became a Thing

It’s unfathomable in our movie-going climate, where the biggest movies are targeted (before a word of their scripts are even written) for summer release, but there was a time when the summer was considered the dumping ground for bad movies, and a time when many moviegoers stayed away from the cinema entirely. (Some critics followed suit; for many years, Pauline Kael went on a summer sabbatical from her duties at The New Yorker, because there was so little worth reviewing.) This was mostly because air conditioning was not yet a part of the theatrical experience, so theaters limited their hours of operation in the summer months, or just shut down. But when air-conditioned theaters became the norm in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, youth-oriented pictures like Bonnie and Clyde, Easy Rider, and American Graffiti did quite well in their summer releases, presumably because their target audience was out of school with time and money on their hands. And Jaws’ phenomenal success confirmed the value of a premium summer release date.

TV Became an Ally Instead of an Enemy

In the early ‘70s, movie studios still regarded television as the competition, and they certainly weren’t going to hand over their money to a rival medium. But according to Biskind, a Columbia producer named Lester Persky convinced the studio to try buying local spots for their Golden Voyage of Sinbad, and they saw results. Two years later, sitting on a lackluster Charles Bronson vehicle called Breakout, Persky convinced Columbia to try another TV ad buy, this time on a national level, and the movie became a surprise hit. Universal eyed this strategy and decided to try it out for Jaws, dropping a then-astonishing $700,000 on TV spots in prime time. “If there were any doubt left about the effectiveness of TV advertising,” Biskind writes, “the movie’s success dispelled it.” And thus, the TV ad buy became an essential part of any big movie’s marketing campaign.

Marketing Became an Art

And subsequently, a marketing campaign would become as important as — if not more so than — the product they were selling. And thus began the notion of using giant ad buys to make movies into events that consumers had to see, preferably on the first weekend. As super-producer Peter Guber told PBS, “These wide releases, these enormous expenditures of prints and advertising in publicity and marketing costs and expenditures, they would create this enormous swell of momentum that would create gargantuan box office from the beginning.” According to Bob Levin, marketing guru and former president of worldwide marketing for the Walt Disney Studios, Sony Pictures Entertainment, and MGM, “what we now call marketing departments were called publicity departments, because it was a publicity-driven business. You can’t go back and find in the early days in the movie business vast amounts spent in advertising. … There was a movie preview, or we call it a trailer, but not a lot of advertising.” Those days are long gone; in today’s climate, the total marketing budget can amount to half of the production budget, and sometimes more.

There’s Money in the Merch

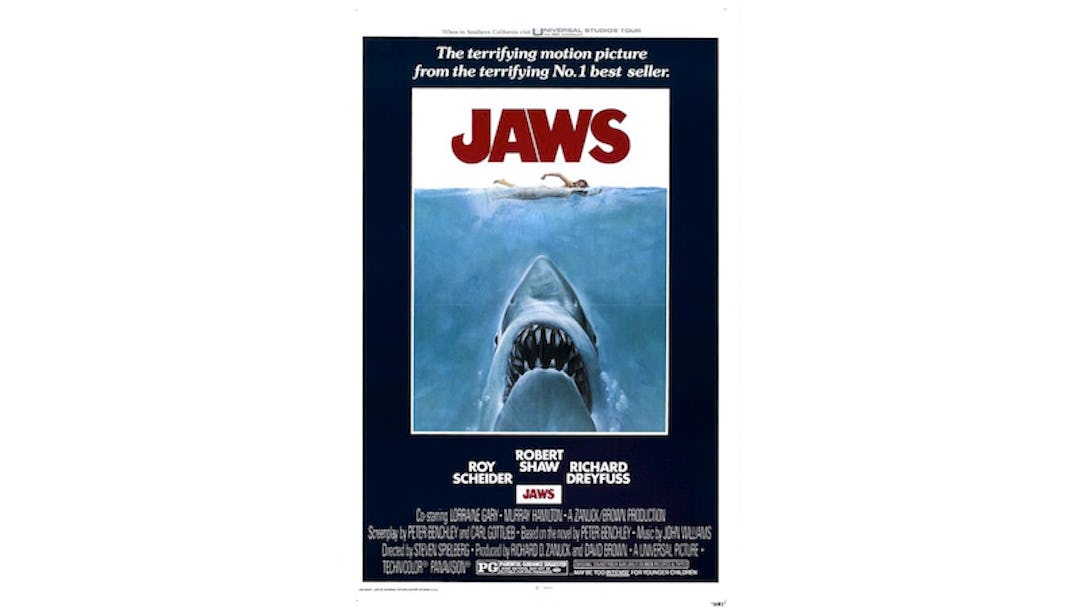

When Jaws became a runaway hit that summer of 1975, everyone looked for ways to cash in. It had what we would now call an easily identifiable “brand” — that iconic John Williams score, which anyone could imitate, and the famed poster imagery, which popped up on everything from T-shirts to political cartoons. As audiences went back to see the movie again and again, savvy manufacturers supplied them with a vast array of Jaws-related products: games, posters, pillows, beach towels, bathing suits, rubber sharks, hobby kits, Halloween costumes, cups, and even belt buckles. Spielberg’s pal George Lucas presumably watched and learned, asking for (and getting) all merchandising rights when he made Star Wars two years later.

Could I Interest You in Some Special Features?

But one of the most interesting ancillary items came in December 1978, when Jaws was the very first title release in North America on the new “LaserDisc” format. Just a year earlier, the Magnetic Video Corporation had introduced the first videocassettes of theatrical movies for consumer use; the era of movie ownership had begun. That first LaserDisc was, as most discs and tapes were in those days, what we now call a “bare bones” release (movie-only), but the Criterion Collection’s first release, 1984’s Citizen Kane, introduced the extra dimension of special features — added content (like commentary, deleted scenes, and featurettes) for movie buffs. And for years, Criterion had that field to itself. But in 1995, Universal re-released Jaws on Laser, in a special edition, THX-approved, 30th anniversary “Signature Collection” edition. That disc included a two-hour “making of” documentary by Laurent Bouzreau (a name spoken in hushed reverence by home media aficionados), which quickly became the gold standard for bonus content — and as notice to major studios that, when DVD began to make a splash over the next few years, special features would have to become a part of everyone’s home media strategy.

The Wide Release Became Standard

Here’s another then-and-now shocker. At the time of Jaws’ release, even the biggest movies were distributed the way prestige pictures and independent movies are now: via a platform release, often opening in only a market or two, gathering buzz, and then slowly working out to secondary markets and additional theaters, often over the course of several months. “Really wide breaks of several hundred theaters or more were reserved for stinkers,” Biskid writes, “enabling studios to recoup their expenses before the picture died.”

But that pattern began to shift with the release of The Godfather in 1972, which opened in five theaters and expanded to over 300 only a week later, quickly advancing its route to the biggest box-office hit of all time to that point. Universal, watching preview audiences’ reaction to Jaws and sensing a similar smash success, opened the picture in over 400 theaters on day one, June 20. Obviously, this became the norm and then some, with day one wide releases expanding to thousands of theaters in the years to come (last week’s Jurassic World, for example, opened on over 4000 screens). And while this meant moviegoers in smaller markets didn’t have to wait as long to see the movies everyone was talking about, Biskind notes that the switch had the adverse effect of “diminishing the importance of print reviews, making it virtually impossible for a film to build slowly, finding its audience by dint of mere quality.”

It Was the Beginning of the End for the “New Hollywood”

Jaws landed in the theaters in the midst of the legendary “New Hollywood” period, when the combusting studios, desperate to lure back moviegoers who’d been put off by the bloated musical extravaganzas of the late ‘60s, gave the keys to their kingdoms to a generation of new, young directors like Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, William Friedkin, and Peter Bogdanovich — film “brats” who learned about the movies via studying them obsessively (often in films schools) rather than working their way up through the studio ranks, as had been the norm. They married their idiosyncratic, personal visions with dusty cinematic genres to create exciting, fresh works like The Godfather, MASH, Chinatown, Mean Streets, and The Last Picture Show — all films that did respectable business, and often better than that. But when Universal and their competitors got a look at the kind of money that could be made by a monster hit like Jaws, small profits from personal pictures were no longer the goal; they wanted a Jaws of their own. And slowly, the business model shifted from several small successes to gambling big on a few potential big rewards — which is a model that remains (and continues to grow) to this day.

The Era of the Blockbuster Began

In a 1995 interview with Premiere’s Nancy Griffin, Spielberg remembered the feeling of Jaws’ success: “I realized— the whole country is watching this! That was the first time it really hit me that it was a phenomenon. I thought, This is what a hit feels like. It feels like your own child that you have put up for adoption, and millions of people have decided to adopt it all at once, and you’re the proud ex-parent. And now it belongs to others. That felt very good.” He, and much of Hollywood, would spend most of their days chasing that good feeling. It only took Jaws 78 days to dethrone Godfather as the all-time box office champ; it was the first movie to break $100 million in the US, besting (before inflation) monster hits like The Sound of Music and Gone With the Wind. As the ‘70s wound down, studios placed their bets on fewer Taxi Drivers and more Supermans; in the following decade, weekend box office totals began appearing in newspapers and on shows like Entertainment Tonight, turning the movie business into a spectator sport where everyone wanted to back a “winner.”

Does any of this diminish the greatness of Spielberg’s movie? Of course not; you can’t blame a film for what happens outside its frame, and if it hadn’t prompted these shifts in the movie business, another film (perhaps Star Wars, perhaps something else) would have. But it can be difficult to reconcile the skill of a movie about a giant shark eating a small village with the fact that the very same movie became a giant shark that ate all of Hollywood.