Wes Craven, who died last week of brain cancer at 76, was a professor before he earned the title of “Frightmaster,” and his public image was more avuncular and professorial than spooky, so it is not surprising that he generally set out to do more than just frighten audiences with his films. Craven’s first hit, The Last House on the Left, offered a bootleg, grindhouse take on The Virgin Spring (an Ingmar Bergman drama, of all things); that film, and The Hills Have Eyes, perfectly reflected the free-floating anxiety and deep distrust of authority figures and institutions that characterized the horror films of the Watergate and post-Watergate era.

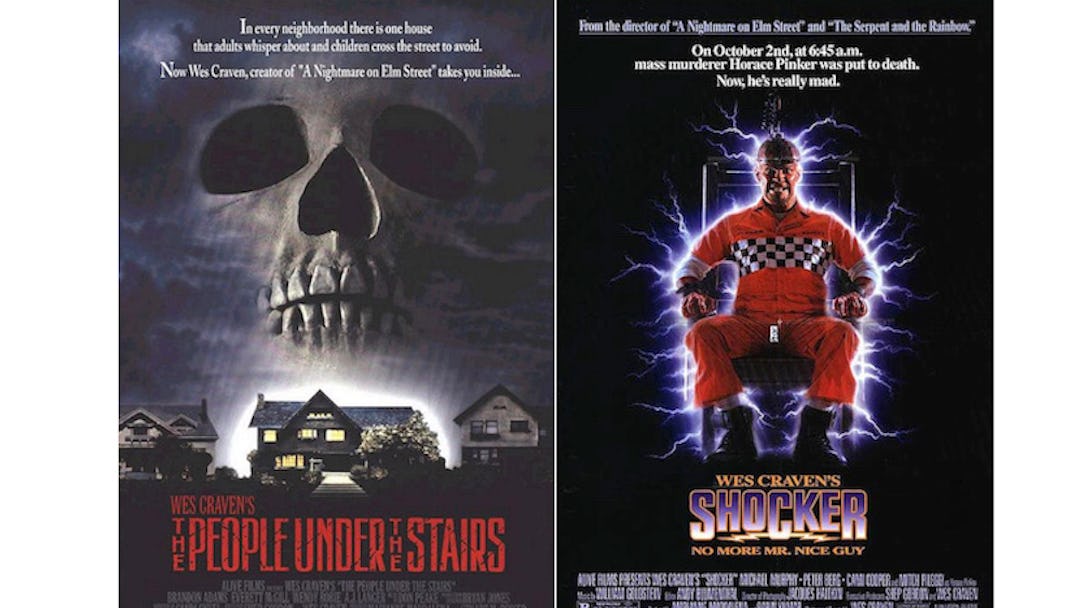

Craven defined an entire subgenre of meta-textual, endlessly self-referential slasher comedies with 1996’s Scream. But before he triumphed with Kevin Williamson’s fiendishly clever deconstruction of the movies that made Craven rich and famous, Craven explored the intersection of media and violence much more clumsily with 1989’s Shocker, which has just been released on Blu-ray by Scream Factory, along with the much more satisfying People Under the Stairs.

Shocker marked the first time Craven turned his attention to the way violence in entertainment bleeds (no pun intended) into real life. But the film’s muddled element of social commentary is just about the only thing that sets it apart from the slew of The Nightmare on Elm Street knock-offs that followed in the wake of the original’s success.

Shocker is only slightly less faithful a remake of The Nightmare on Elm Street than the film’s actual 2010 remake (it might as well be called Bad Dreams on Electric Avenue). A blatant act of self-cannibalization, Shocker is shameless enough to even have hopelessly whitebread protagonist Jonathan Parker (Peter Berg, whose performance here suggests his transition to filmmaking was a smart/necessary move) discern the movements and locations of deranged mass murderer Horace Pinker (The X-Files’ Mitch Pileggi) through a series of moody nightmares. Yes, nightmares.

And just like Nightmare on Elm Street, Shocker revolves around a serial killer who terrorizes an entire community with his crimes, then becomes a shape-shifting, undead, murderous ghoul after he is killed in the name of justice. In Shocker, that means that after Horace Pinker is put to death through electrocution, his spirit lives on as a sort of satanic electrical current that leaps first from body to body, not unlike the alien in The Hidden (directed by Jack Sholder, the man who took over the reins from Craven for Nightmare on Elm Street 2), and then from television show to television show and movie to movie in a climactic set-piece that suggests a horror movie remake of the John Ritter comedy Stay Tuned.

To give Craven’s seriously dopey, insanely derivative nonsense more credit than it probably deserves, Pinker functions here as the malevolent spirit of television and violent entertainment rendered flesh, a ghoul who fixes televisions for a living, and inhabits them after dying. As social commentary, Shocker is hopelessly muddled; as a horror film, it’s a dim-witted nonstarter further hindered by the weird stunt casting of John Tesh as a newscaster who delivers reams and reams of expositions (and not wicked-smooth jazz, as his custom) and Dr. Timothy Leary as a televangelist who gets caught up in Horace Pinker’s mad dash through the dregs of our television-warped culture.

Pileggi gives his deranged killer an unstoppable tenacity that’s better than Craven’s uncharacteristically dumb script merits, but otherwise Shocker is best understood as an extremely rough draft of the themes Craven would explore much more intelligently and satisfyingly in Wes Craven’s New Nightmare and then in the Scream series.

Craven’s creations are woven deep into the fabric of American culture. He was a genius at creating neighborhood mythologies so compelling that they became part of the mythology of American pop culture. Freddy Krueger may have started off as Elm Street’s bogeyman, but now he belongs to all of us; if it doesn’t already, his knife-glove might as well be displayed alongside Fonz’s leather jacket and Archie Bunker’s recliner in the Smithsonian.

The frustration of Shocker is that a man so gifted at creating worlds, whose films are part of the folklore of contemporary life, was content to simply recycle Nightmare on Elm Street for seemingly mercenary rather than creative purposes. And part of the appeal of 1991’s The People Under the Stairs lie in Craven creating a vivid, multi-dimensional world that reflected and distorted the socioeconomic concerns of the time in a gothic funhouse mirror.

When it comes to mixing social commentary with genre filmmaking, Craven fared much better with The People Under the Stairs, a cult hit that can loosely be grouped into the horror genre but that derives much of its strange and enduring fascination from the way it freely mixes genres, tones and sensibilities.

The film takes place in an inner city ghetto ruled by The Robesons (Everett McGill and Wendy Robie), a brother and sister pair who are the gruesome, inveterately corrupt product of generation upon generation of incest and in-breeding. Despite being brother and sister, almost assuredly with benefits, the Robesons are overtly modeled on Ronald and Nancy Reagan.

Indeed, McGill, who is perhaps best known for his work on Twin Peaks, often suggests a sort of deranged, Devo conception of Reagan as a murderous yet easily fooled slapstick villain, all creepy faux-wholesomeness and morning anchor waxen handsomeness. The Robesons are brutal slumlords who keep armies of feral children, some with their tongues cut out, hidden in the secret passages of a mansion that functions as a massive haunted house filled with ominous secrets.

The gifted child actor Brandon Adams stars as a black boy nicknamed “Fool” who enters the Robesons’ deadly lair seeking a fortune in gold coins, which will allow him to keep his family from being evicted and pay for his sick mother’s hospital bills. Once inside the Robeson’s haunted mansion, Fool strikes up a friendship with Alice (A.J Langer), a beautiful young innocent (Alice in Slaughterland, as it were) who has been imprisoned and tormented by the sinister brother-sister twosome but has avoided the fate of the children inside the walls through unthinking obedience.

As an allegory for the brutal societal iniquities and ever-growing gulf between the rich and the poor that only widened during the Reagan-Bush era, The People Under the Stairs could scarcely be more obvious than it already is. It depicts capitalism as a ghoulish, nefarious force that brutally oppresses the literally starving and abused underclass and props up an ownership class that isn’t just depicted as being greedy and amoral, but relentlessly evil.

Yet the bludgeoning nature of the film’s social commentary ends up working in its favor. People Under the Stairs is not a subtle film, or an overly artful one. But, especially considering the film it followed, it is wonderfully original—part socio-economic fable and part kooky haunted house movie. At its best, The People Under the Stairs has the power and simplicity of a contemporary inner-city fairy tale. The film’s tone varies wildly from scene to scene; like Shocker, The People Under the Stairs has a surprising appetite for cartoonish slapstick comedy, and McGill’s plasticine riff on The Great Communicator is at once comically pathetic and genuinely frightening. Directing actors hasn’t always been Craven’s strong suit, but The People Under The Stairs benefits from a terrific lead in Adams and the automatic gravitas of supporting players like Ving Rhames and Bill Cobb.

The gulf between the haves and have-nots has only widened since the film’s release, so it’s a little perplexing that in a world where Last House On the Left gets remade and The Hills Have Eyes has both a remake and a sequel to said remake, a remake-crazy horror movie world hasn’t turned its attention to remaking The People Under The Stairs, although before he died, Craven was reportedly developing the movie as a television series for Syfy. Assuming it makes it to air, it’ll be interesting to see how People Under the Stairs fares today, since it is both an indelible document of the Reagan-Bush era and the Big Lie that was trickle-down economics, and a movie whose primal simplicity and keen grasp of archetypes render it strangely timeless.

And though The People Under the Stairs is not Craven’s best film, it is a lovely illustration of what made him such an important and enduring filmmaker. Craven was a brilliant storyteller whose best films weren’t just scary; like People, they were about something important, and if they sometimes overreached, or didn’t entirely hold together, that was often a byproduct of Craven’s enviable and all-too-rare ambitiousness.