The seemingly uncomplicated good vs. evil narrative and the complexity of subsequent conflicts, coupled with boomer nostalgia, has allowed modern viewers and readers to view WWII through rather rose-colored glasses; it was “the last good war” we’re told. But in this instance, “good” does quite a bit of heavy lifting.

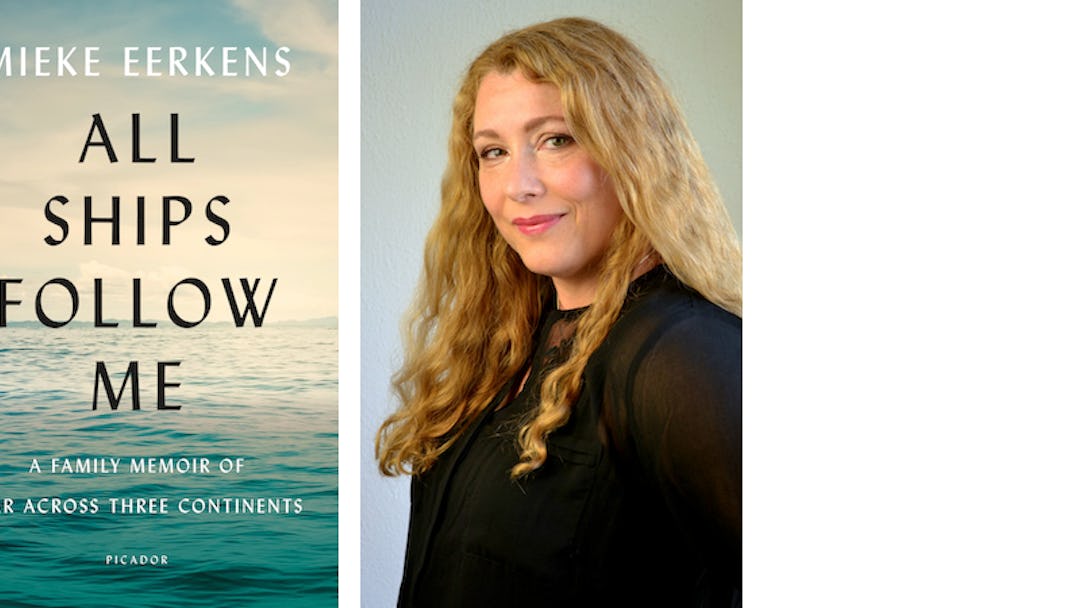

All Ships Follow Me: A Memoir of War Across Three Continents by Mieke Eerkens (out this week from Picador) complicates the conflict. Eerkens’s father, then a child, was interned a Japanese concentration camp in the Dutch East Indies; her mother was sent to a children’s home after her parents were arrested as Nazi collaborators in the Netherlands. “The more I hear my parents’ stories and see how their war experiences influenced the people they became and how I was raised,” she writes, “the more I understand that war injures without prejudice. It injures participants and bystanders and all the people who come after them.”

We’re proud to present an excerpt from this riveting memoir.

FROM “THINGS” Pacific Palisades, California, 1981 My father tumbles in from the cold, his hair blown every which way. He is carrying a fractured lamp. “Look at this! This is a perfectly good lamp someone’s just throwing away,” he states incredulously, ignoring my mother’s objections as he begins to apply silver duct tape over the fissures in the lamp’s bright orange base. “I don’t want that broken lamp in here,” my mother complains, and we all watch the word land like a flaming paper bag on my father’s doorstep. Broken. Of course he steps on it. The word is too loaded for him to accept. “It’s not broken.” He spits the word at her. “It has a small crack. It’s not broken. This lamp still works. You guys think everything is broken if it has a little crack.” Admitting that something is broken is an indefensible resignation, to his mind. Indeed, there isn’t much that cannot be repaired with duct tape, in my father’s estimation, and he routinely rescues the most tattered items from curbsides all over town to render them whole again. He is egalitarian and unbiased in his approach. When the leg breaks off the eighteenth- century carved wedding chest, it too is wrapped back into place with duct tape. My mother mutters, “That’s your camp syndrome,” referring to his years as a child in the internment camp, where he had nothing and nearly starved to death. Thanks to his “camp syndrome,” our garage is packed floor to ceiling with things. Things like boxes he hasn’t looked at for decades. Things like a massive, inoperable, rusted iron drill press from the 1940s. Things like cracked lawn chairs and carpet remnants from other people’s houses and gray institutional metal desks missing drawers and nonfunctioning coffeemakers. “Look at that. You see? Perfectly good,” my father says, regarding his duct- tape resurrection of the lamp. Perfectly goodis one of my father’s most used phrases. The lamp goes on his nightstand, right beside another duct- taped lamp. It stays there for the next twenty years and is never turned on. It’s just one example of how my siblings and I learn in myriad unspoken ways growing up that we are perpetually balanced on the precipice of loss, and to hold on white- knuckled to every object that crosses our paths, despite our relative privilege and financial security. We learn to transfer our fears onto the things we can see and hold, because there is so much we have no control over losing. Despite my best efforts, despite growing up surrounded by wealth, the anxiety creeps into my own behavior. I don’t seem to be able to discern what’s normal or neurotic as I age. I see more and more schisms erupting each day. With irritation and surprise, I recognize my father in me when I start to recycle my dental floss, rinsing it and setting it next to my toothbrush for a second use. But I also cannot stop doing it. Without being aware of it, I seem to have appropriated the “poverty mentality” my sister, a psychologist, describes us as having, a deeply ingrained belief about scarcity. At Christmas in our family, we all unwrap our gifts carefully so that we don’t rip the paper, and we fold it up to use again, winding the ribbons around saved paper towel rolls. Sometimes there is another person’s name crossed out on the packages we open, the paper passed down from a prior year. I never questioned this practice until later in life; I thought it was what everybody did. It is so ingrained in me that it is still always a slight shock to watch somebody open a gift I’ve given them by tearing into it and throwing the paper aside or stuffing it into a garbage bag. At home when I was growing up, our kitchen drawers were filled with hundreds of rubber bands from the daily newspaper, corks, stacks of rinsed plastic yogurt containers, wads of plastic bags. Today, my drawers are filled with rubber bands, corks, plastic yogurt containers, and plastic bags. I don’t know how that happened. I recall visiting my father when he relocated to Missouri for a brief period, before my mother could join him. I opened the cupboards and they were filled with stacks of plastic and Styrofoam containers he had saved from take- out meals, straws, and flimsy pie tins. At the time, I chastised him and could not understand his compulsion to keep everything. Now, after mining his war experiences, after knowing how he bartered his only possessions for food in the internment camp, after knowing that every tiny thing that crossed his path was a gift of survival in the camp—a cork, a pencil, a piece of paper, a cup, I know that this is a testament to an unrelenting drive to triumph over the unpredictable circumstances in life. It’s spectacular, his will to survive, even when the rest of us don’t see any perceived danger. It’s in his bones to prepare for what he can. When I encounter his hoarding tendencies now, accompanied by his insistence that everything could be useful “someday,” my exasperation is tempered by a realization that this is precisely what got him through a war that killed his friends. With thousands of miles between us, and the liberty of reflection gained by being removed from the day- to- day frustrations of living with the mess, I have gratitude for that quality. Now I think that the “camp syndrome” doesn’t need to be an apology or an excuse for his behavior. Maybe it doesn’t need to be a detriment at all. Maybe when the deluge comes, my father will fashion an ark out of lawn chairs, rubber bands, and duct tape, and he will show the rest of us how to float.

Excerpted from All Ships Follow Me: A Family Memoir of War Across Three Continents. Copyright © 2019 by Mieke Eerkens. Published by Picador USA. All rights reserved.