Throughout our lives, we’ll encounter colleagues, significant others, and friends who seem impossible to know – but often, the people we understand least are the ones we knew first. Such is the case of Deborah Burns, who grew up in privilege in the 1950s grasping for the attention and approval of her mother, a wealthy beauty who mostly left the duties of child-rearing to others while she enjoyed the spoils of her wealth.

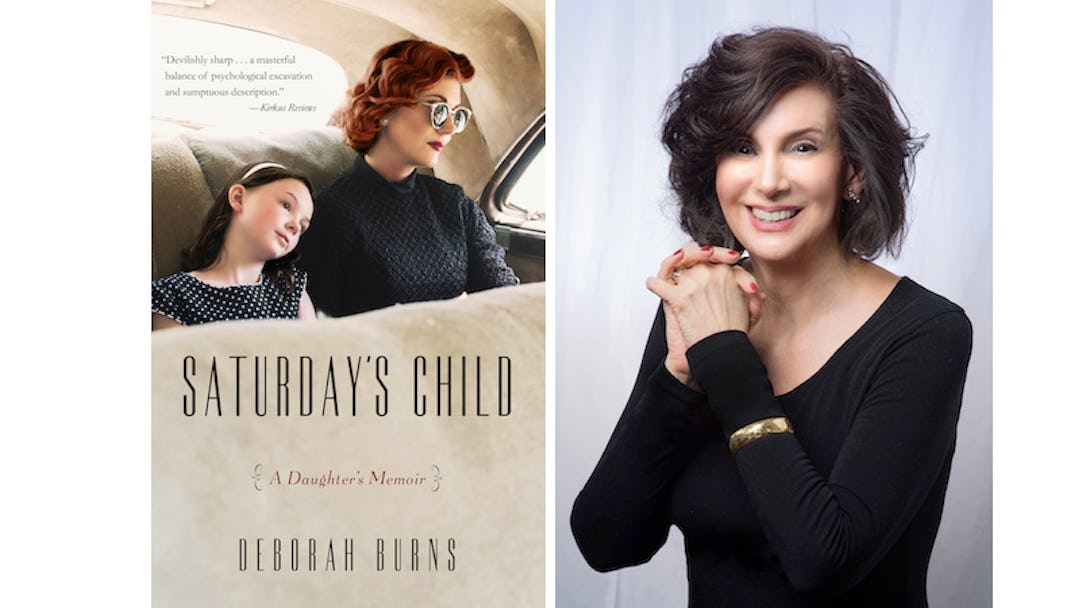

Burns would become a high-ranking executive at Elle magazine, but she remained haunted by the memory of her late mother, and attempted to reckon with how their relationship had affected her life. To do so, she wrote Saturday’s Child (out this week from She Writes Press), a moving memoir about a daughter’s quest to understand her mother, and come to terms with her complexities.

We’re proud to present this excerpt.

FROM CHAPTER TWO My hand started waving as soon as I sensed my mother’s car about to round the last curve before the hotel. I never failed to anticipate her arrival every summer Saturday, not even once, not even by a second. When she stepped out, I threw my arms around her waist, careful to angle my body back a bit so my bathing suit would not dampen her. A half embrace, but we were together again. Even if her hug wasn’t quite as tight as mine, I could tell that she had missed me too. A quick change into one of her Emilio Pucci–inspired sarongs, and then we would trek to the enormous pool with all the other guests. My towel was already on the hill’s coarse grass from the morning, and she would join me on it for a few moments so I could cover her back with oil. Then I’d watch as she first glossed her face, then her chest and arms and finally her legs, slightly raised to reach her arched feet. Even now, the scent of Bain de Soleil transports me to another time and place. Back in the water, I kept one eye on her as I swam with the other children. Always holding a cigarette aloft, she’d laugh with the friends who orbited her, admirers who vied for proximity seeking some rub-off effect, or so it seemed to me. She seduced the world and I was no exception. Once an hour she’d pin up her tumbling red mane, tie a sheer kerchief around, and come in for a dip. Everyone knew to stop splashing. She slowly submerged up to her shoulders and began her sidestroke once around the circumference of the pool. That signature stroke was completely her, effortlessly gliding sideways through life without ever going too deep. After all, leaving the surface would wet her hair. When I was very young, our pool ritual was a public and private gift. Before or after the side-stroking—sometimes before and after on a really great day—my mother would press her body down on the rope that separated the children’s side of the pool and slide across. Scooping me up, she’d ease back over to the grown-up side (where the water was almost as low, but I still felt as if I was entering a forbidden realm). With a bend of her slippery knees so the water would just reach her neck, I’d climb on to face her, weightless, my little hands, arms, and feet sliding on her shoulders and legs. A smiling pause to build the anticipation, and then she’d begin her bouncing game. “Bah-dum, bah-dum,” she would singsong, “bah-dum, bah-dum,” as we bobbed and turned round and round together. Her breath, her closeness, her blue eyes on me as the cool water beaded on our skin was like nothing else. If I close my eyes, I can still feel that joy. The ramshackle little hotel that my father’s family had built was upstate New York’s Italian safe haven. And my mother—Dorothy, a.k.a. Dotty—reigned supreme as its brightest non-Italian star. The grounds of the resort and its cast of characters anchored us both in the country for three months every year. As soon as school was over, I was ready to leave the city, impatient—for once—as if I were some unruly child. I’d roll down the window as we drove and tick off the markers to the almost there stop in throwback Marlboro. The town’s two storefronts were ready to greet us—a bakery and Jack’s Variety Store, which seemed to hold all the plastic and paper mysteries of the universe behind its screen door. We’d emerge with a bag of toy horses, coloring books, crayons, and enough paint-by-numbers sets to last the summer, and a second bag filled solely with connect-the-dot books. My fascination with drawing lines between randomly placed dots to reveal something surprising knew no bounds. Then fifteen minutes more on the narrow looping roads, up and down hills, past dense trees, and over a little stone bridge. Almost there, almost. A straight patch and then there it was, the grand field with the pool in the distance on my right, the house my grandfather had once lived in on the left, and straight in front of me the three-story hotel he had named the Canzoneri Country Club. Arriving, I felt like I was finally home. Bought by my father’s brother, Tony Canzoneri—also known as the lightweight boxing champion of the world—it had been, in its 1940s heyday long before me, the Italian destination for anyone who was anyone with a vowel ending their last name. Some of the colorful guests were on the sketchier side; some even signed the check-in register with aliases, parking their families at the hotel for the summer season while they traded sunshine for shady city business during the week. What those men actually did was anybody’s guess. No one dared ask too many questions.

Excerpted from Saturday’s Child. Copyright © 2019 by Deborah Burns. Published by She Writes Press. All rights reserved.