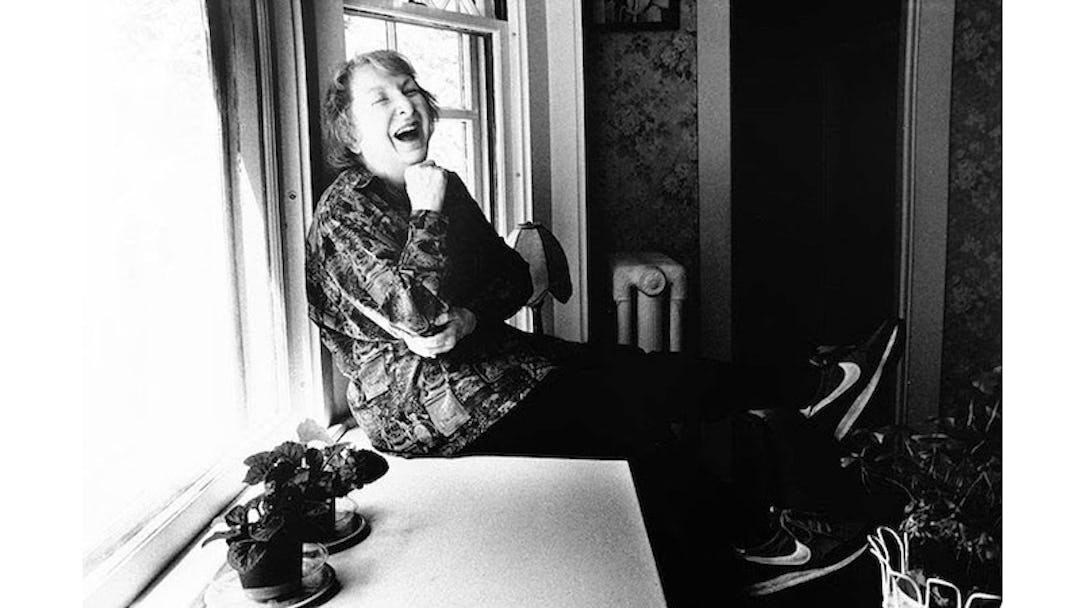

June 19 marks 100 years since the birth of Pauline Kael, the most influential film critic of her era, and one of the most noteworthy cultural critics of all time. (Here in New York, the Quad Cinema is celebrating with “Losing it at the Movies: Pauline Kael at 100,” a retrospective program featuring some of the films she championed, and a few she famously abhorred.)

There’s so much to consider about Kael – from her many controversies to her fascinating personal life to the films and filmmakers that fell on the right and wrong side of her poison pen – that it’s easy to lose sight of what made Kael so special: the quality of her writing. But there really was no one who wrote about the medium like she did (though many have certainly tried), combining passion, intellect, hyperbole, vernacular, and history into a whirlwind of prose that could leave the reader breathless. And often, her insights were so keen, the specificity of her time didn’t matter; her pieces on the state of the industry or the audience are, if anything, more accurate today.

In commemoration of Kael’s centennial, here are a few of this fan’s favorite passages from her work.

From “Movie Brutalists” (1966):

“Aesthetically and morally, disgust with Hollywood’s fabled craftsmanship is long overdue. I say fabled because the “craft” claims of Hollywood, and the notion that the expensiveness of studio-produced movies is necessary for some sort of technical perfection or ‘finish,’ are just hucksterism. The reverse is closer to the truth: it’s becoming almost impossible to produce a decent-looking movie in a Hollywood studio. In addition to the touched-up corpses of old dramatic ideas, big movies carry the dead weight of immobile cameras, all-purpose light, whorehouse décor. The production values are often ludicrously inappropriate to the subject matter, but studio executives, who charge off roughly 30 percent of a film’s budget to studio overhead, are very keen on these production values which they frequently remind us are the hallmark of American movies.”

From “Movies on Television” (1967)

“But when people say of a “big” movie like High Noon that it has dated or that it doesn’t hold up, what they are really saying is that their judgment was faulty or has changed. They may have overresponded to its publicity and reputation or to its attempt to deal with a social problem or an idea, and may have ignored the banalities surrounding that attempt; now that the idea doesn’t seem so daring, they notice the rest. Perhaps it was a traditional drama that was new to them and that they thought was new to the world; everyone’s “golden age of movies” is the period of his first moviegoing and just before—what he just missed or wasn’t allowed to see.”

From “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967)

“I would suggest that when a movie so clearly conceived as a new version of a legend is attacked as historically inaccurate, it’s because it shakes people a little. I know this is based on some pretty sneaky psychological suppositions, but I don’t see how else to account for the use only against a good movie of arguments that could be used against almost all movies. When I asked a nineteen-year-old boy who was raging against the movie as “a cliché-ridden fraud” if he got so worked up about other movies, he informed me that that was an argument ad hominem. And it is indeed. To ask why people react so angrily to the best movies and have so little negative reaction to poor ones is to imply that they are so unused to the experience of art in movies that they fight it.”

From “Faces” (1968)

“His deliberately raw material about affluence and apathy, loneliness and middle age, the importance of sex and the miseries of marriage may not say any more about the subject than glossy movies on the same themes, and the faces with blemishes may not be much more revealing than faces with a little makeup, but the unrelieved effort at honesty is, for some people, intensely convincing. When it’s done as psychodrama rather than as entertainment, they seem to accept all this bruising-searing stuff, the sad whore and the tender hustler, and the false-laughter bit, and the-lies-people-live-by, etc. Watching the kind of drunken salesmen one would have sense enough to avoid in life can, I suppose, seem an illumination. Watching a fat, drunken old woman fall on top of a man she has just begged for a kiss can seem an epiphany. There are scenes in Faces so dumb, so crudely conceived, and so badly performed that the audience practically burns incense.”

From “Trash, Art, and the Movies” (1969)

“A good movie can take you out of your dull funk and the hopelessness that so often goes with slipping into a theatre; a good movie can make you feel alive again, in contact, not just lost in another city. Good movies make you care, make you believe in possibilities again. If somewhere in the Hollywood-entertainment world someone has managed to break through with something that speaks to you, then it isn’t all corruption. The movie doesn’t have to be great; it can be stupid and empty and you can still have the joy of a good performance, or the joy in just a good line. An actor’s scowl, a small subversive gesture, a dirty remark that someone tosses off with a mock-innocent face, and the world makes a little bit of sense. Sitting there alone or painfully alone because those with you do not react as you do, you know there must be others perhaps in this very theatre or in this city, surely in other theatres in other cities, now, in the past or future, who react as you do. And because movies are the most total and encompassing art form we have, these reactions can seem the most personal and, maybe the most important, imaginable.”

From “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid: Bottom of the Pit” (1969)

“Not every movie has to matter; generally we go hoping just to be relaxed and refreshed. But because most of the time we come out slugged and depressed, I think we care far more now about the reach for something. We’ve simply spent too much time at movies made by people who didn’t enjoy themselves and who didn’t respect themselves or us, and we rarely enjoy ourselves at their movies anymore. They’re big catered affairs, and we’re humiliated to be there among the guests.”

From “Stanley Strangelove: A Clockwork Orange” (1972)

“The movie’s confusing—and, finally, corrupt—morality is not, however, what makes it such an abhorrent viewing experience. It is offensive long before one perceives where it is heading, because it has no shadings. Kubrick, a director with an arctic spirit, is determined to be pornographic, and he has no talent for it. In Los Olvidados, Buñuel showed teen-agers committing horrible brutalities, and even though you had no illusions about their victims—one, in particular, was a foul old lecher—you were appalled. Buñuel makes you understand the pornography of brutality: the pornography is in what human beings are capable of doing to other human beings. Kubrick has always been one of the least sensual and least erotic of directors, and his attempts here at phallic humor are like a professor’s lead balloons. He tries to work up kicky violent scenes, carefully estranging you from the victims so that you can enjoy the rapes and beatings. But I think one is more likely to feel cold antipathy toward the movie than horror at the violence—or enjoyment of it, either.”

From “Coming: Nashville” (1975)

“[T]he picture is unmistakably Altman—as identifiable as a paragraph by Mailer when he’s really racing. Nashville is simply “the ultimate Altman movie” we’ve been waiting for. Fused, the different styles of prankishness of M*A*S*H and Brewster McCloud and California Split become Jovian adolescent humor. Altman has already accustomed us to actors who don’t look as if they’re acting; he’s attuned us to the comic subtleties of a multiple-track sound system that makes the sound more live than it ever was before; and he’s evolved an organic style of moviemaking that tells a story without the clanking of plot. Now he dissolves the frame, so that we feel the continuity between what’s on the screen and life off-camera.”

From “Fear of Movies” (1978)

Discriminating moviegoers want the placidity of nice art—of movies tamed so that they are no more arousing than what used to be called polite theatre… This is, of course, a rejection of the particular greatness of movies: their power to affect us on so many sensory levels that we become emotionally accessible, in spite of our thinking selves. Movies get around our cleverness and our wariness; that’s what used to draw us to the picture show. Movies—and they don’t even have to be first-rate, much less great—can invade our sensibilities in the way that Dickens did when we were children, and later, perhaps, George Eliot and Dostoevski, and later still, perhaps, Dickens again. They can go down even deeper—to the primitive levels on which we experience fairy tales. And if people resist this invasion by going only to movies that they’ve been assured have nothing upsetting in them, they’re not showing higher, more refined taste; they’re just acting out of fear, masked as taste. If you’re afraid of movies that excite your senses, you’re afraid of movies.”

“Why Are Movies So Bad? Or, The Numbers” (1980)

“To put it simply: A good script is a script to which Robert Redford will commit himself. A bad script is a script which Red-ford has turned down. A script that “needs work” is a script about which Redford has yet to make up his mind. It is possible to run a studio with this formula; it is even possible to run a studio profitably with this formula. But this world of realpolitik that has replaced moviemaking has nothing to do with moviemaking. It’s not just that the decisions made by the executives might have been made by anyone off the street—it’s that the pictures themselves seem to have been made by anyone off the street.”

Quad Cinema’s “Losing it at the Movies: Pauline Kael at 100” runs June 7-20.