Confession: We’ve been watching In Search Of… lately. If you’re not familiar with it, this was a syndicated series, hosted by Leonard Nimoy, that ran six seasons in the late 1970s and early 1980s, in which Mr. Nimoy and his producers investigated unexplained phenomena the world over, with the help of scientific “experts” and moody synthesizer music. And while Bigfoot, UFOs, and the Bermuda Triangle were the marquee episodes, the most unsettling may have been those exploring inexplicable geographic events – statues and monuments and walls that simply don’t seem possible, considering the materials and technology available to ancient civilizations.

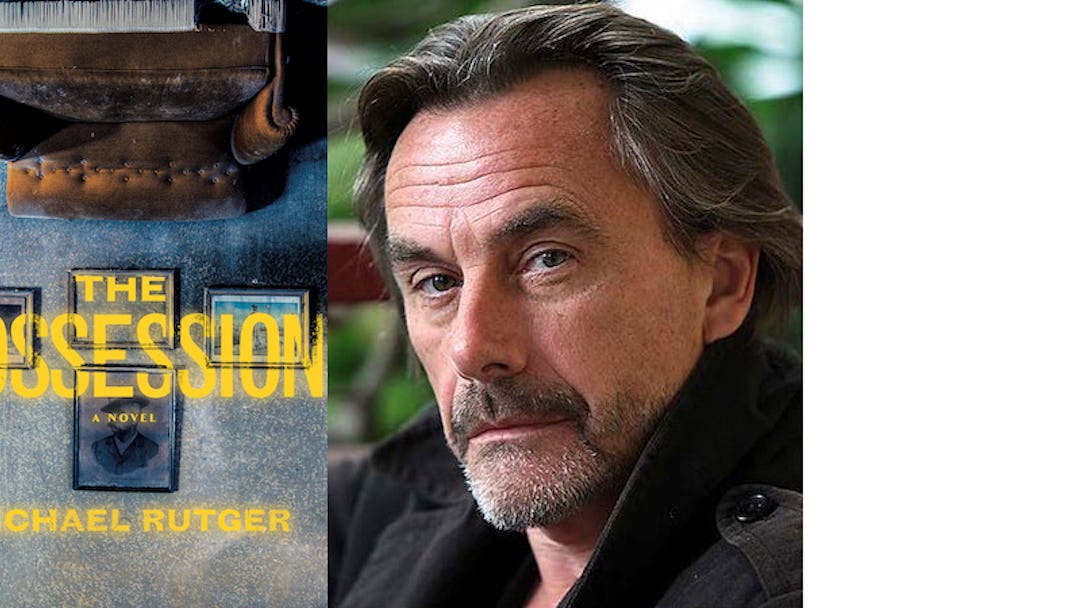

In Michael Rutger’s new book The Possession (out now from Grand Central Publishing), Nolan Moore, host of an In Search Of…-style show called The Anomaly Files, uncovers a similar mystery: in the woods outside the small town of Birchlake, California, residents have been baffled for generations by odd, low, spiraling walls. And the recent disappearance of a high-school girl in town may be unrelated… or it might not.

We’re pleased to present this excerpt from this gripping book:

FROM “THE POSSESSION”:

Everybody’s heard of the Nazca Lines, in Peru. If you haven’t, look them up. I’ll wait. Okay, you know what? Just listen. The Nazca Lines are hundreds of extremely straight lines of scraped earth— embellished with vast parallelograms and narrow triangles longer than a skyscraper is tall, along with massive animal and plant geoglyphs of eerie sophistication. Believed to have been created between 500 bc and ad 500, the lines are assigned to the usual alleged yesteryear obsessions of celestial observation or “ceremonial walkways,” though neither makes much sense. Erich von Däniken and allied ancient astronaut nuts went all in on the idea that they were interstellar landing strips, but it’s hard to imagine why you’d require so many, that are so long, and repeatedly and chaotically cross, or why you’d need vast, stylized pictures of spiders and monkeys and hummingbirds for this purpose (unless they were the logos of alien cruise ship companies).

Much less famous are the Sajama Lines in Bolivia, again formed by scraping away rocks to reveal lighter undersoil and stretching for up to twenty kilometers across arid and unforgiving landscape. There are none of the cool geoglyphs found at Nazca, but they spread over twenty-two thousand square kilometers, making them fifteen times the size. There are further examples that are barely known beyond academics in the relevant countries—like the Big Circles, twelve massive rings of low stone walls in the Jordanian desert, ranging from seven hundred to fifteen hundred feet in diameter. Nobody knows who made them, or why.

The area around the nearby Azraq Oasis has hundreds of more complex circular structures dated to around two thousand years ago. Still in Jordan, there’s a ninety-three-mile-long wall called Khatt Shebib, which stretches across a random stretch of desert. It is not (and has never been) high enough to form a barrier against anything. At times two walls run in parallel, pointlessly. Over in Kazakhstan, meanwhile, there’s a collection of two hundred mounds, ramparts, and shapes—including a vast square with a diagonal cross, and a three-legged swastika—known as the Steppe Geoglyphs, some of which are believed to be eight thousand years old.

And so on and on. There are famous examples in Europe, too— like the stone lines at Carnac in France. More are being discovered every year, now that people have access to Google Maps. But this kind of thing is only found in other, dusty and ancient countries, right? The weird foreign ones?

Wrong.

There are lines in the United States, too. I’m not talking about odd collections of megalith-type structures such as Mystery Hill in New Hampshire, or Gungywamp in Connecticut—or even the stone chambers in New England that conventional archeology airily dismisses as “root cellars.”

Stranger, to me, are the stone walls.

There’s no question that the scattered communities of sixteenth and seventeenth century New England would have needed to organize their environment, and likely spent some time piling up rocks for that purpose. A significant number of stone walls may be merely that. But in 1872 the US Department of Agriculture estimated there were 240,000 miles of walls in New England. Yes, all those zeros are correct. And still better than my Amazon sales ranking. A further report in 1939 nudged it up to 259,000 and still didn’t factor in several areas that have especially large numbers of walls: modern researchers put the figure closer to 500,000.

That’d get you to the moon and back.

That’s a lot of walls.

Let’s put this in the context of the times, too—the period when (according to the few archeologists who’ve considered the phenomenon for five seconds) early settlers allegedly erected these features. In the highlands of Massachusetts there’s a town called Hawley, for example. It was settled in 1770 and has never been large: its population in 1790 was 539, it peaked at 1,089 in 1820, and then it slipped back to 600 by 1879. These were farmers living in a harsh, rugged landscape—chopping wood, growing food, performing all the disappointingly tiring tasks required to hack out an existence in the New World.

Yet this small community apparently also had the time to build over a thousand milesof stone walls.

Their walls share odd characteristics with others across New England, lines that could circumnavigate the Earth twenty times. Let’s run with the idea they’re to keep wanderlusting sheep or errant chickens in check. In which case, why are some twelve feet high? And yet others built so low that they wouldn’t form a barrier to a determined toddler? Why do some veer all over the place, in jagged or curling or looping lines? Why do so many start and stop suddenly and without apparent reason, failing to form a useful boundary? Why do others go through swamps, or up cliffs, or over mountains that were never farmed, sometimes scaling slopes that are hard to navigate without going down on hands and knees?

Dunno, right? So let’s just ignore them.

That happens a lot. In the New York Timesof December 18, 2002, you’ll find a piece about a group of scientists diligently mapping the bottom of the Hudson River with sonar. They found evidence for several hundred of the ships recorded to have sunk there over the previous four centuries, which is doubtless fascinating if you have a thing for old boats, which personally I don’t. There’s a wealth of chatty information about the wrecks and items that divers had found—including leather, clothes, and food (blueberries, and a potato) that’d been held together by the mud for a couple hundred years.

But then, in the middle of the piece is an odd little paragraph. In throwaway style it’s revealed that the survey also found “submerged walls more than 900 feet long, that scientists say are clearly of human construction,” adding that the last time the water levels were low enough for building on dry land was . . . three thousand years ago.

Then they go back to drooling over the wreckage of Revolutionary-era ships, and the wall’s never brought up again. If you don’t believe me, look it up—though you’ll have to head straight to the NYTpiece because it’s not mentioned anywhere else that I can find, and it’s my job to look for this stuff.

Doesn’t that seem weird to you? Half a mile of stone wall, built three thousand years ago, cited in the New York Timesas discovered and mapped by real, named scientists—and yet everybody’s “Huh, whatever”?

As The Anomaly Fileshas pointed out on many occasions, there’s an awful lot of “Huh, whatever” in American archeology— especially when it comes to the country’s prehistory. Which is curious.

Almost as if there are secrets we’re not being told.

Excerpted from “The Possession” by Michael Rutger. Copyright © 2019 by Michael Rutger. Reprinted with permission from Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.