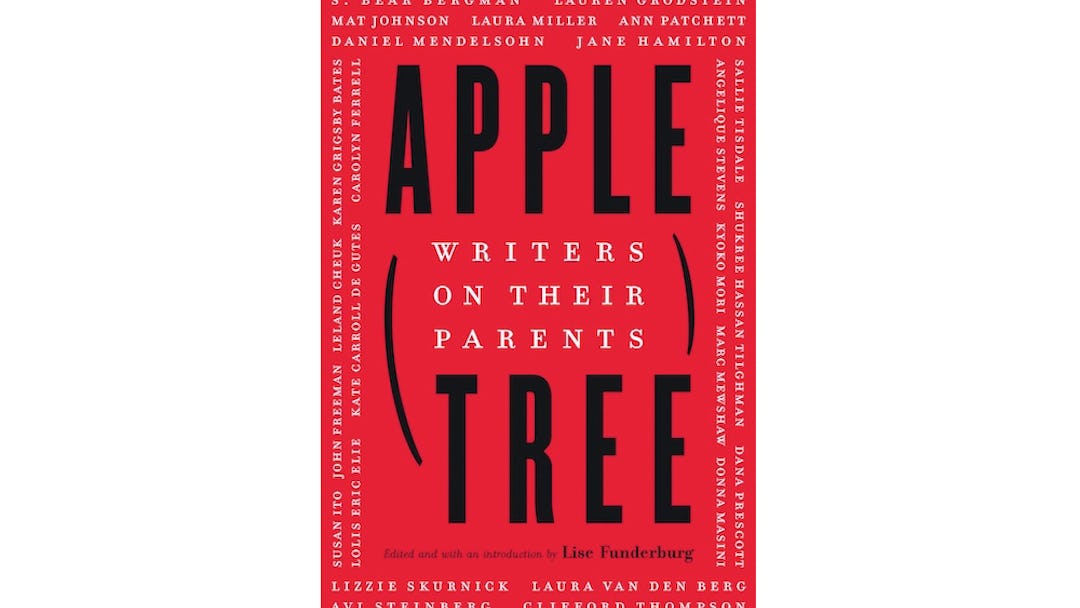

One of the most disturbing moments of adulthood - and most, if not all, of us have it - is that terrible flash when we react to something without thinking, and realize we've done so exactly as our parents would. In the new anthology Apple, Tree: Writers on Their Parents (out now from University of Nebraska Press), author and editor Lise Funderburg collects essays from more than two dozen writers (including Ann Patchett, Daniel Mendelsohn, Jane Hamilton, and S. Bear Bergman) that grapple with that moment, adult children re-examining their relationships with a parent after stumbling upon an inherited, often unsettling, character trait.

We're pleased to present this excerpt from the introduction, in which Funderburg tells her own story of investigation and realization:

FROM THE INTRODUCTION TO 'APPLE, TREE: WRITERS ON THEIR PARENTS":

Spring, a few years ago: I dipped into a West Philadelphia coffee shop for something cold and caffeinated. I was on my way to teach, in the hometown I’d returned to after decades, and I needed a boost before facing three hours of manuscript scrutiny in an airless basement, the realm of adjuncts who have no pull. The caféwas less than a mile from the neighborhood where I had been born and raised: a progressive nest of professors and political activists and inter-something families, where sycamore roots erupted from brick sidewalks and Victorians that had been sectioned into apartments were being reconstituted as single-family homes.

I demolished half of my drink in one swallow and carried the remainder outside. A bright sun snapped me to attention; I tossed the cup into the nearest trashcan. The automaticity of that act caught me up short, as did the sense of having done something wrong. Look at that, I said to myself, I just broke a rule I didn’t know I followed.

I crossed the street, entered my building, and descended its wide marble staircase.

Of course, I thought. My actions made perfect sense. Perfect sense for a black man in the 1930s, living in the Jim Crow South. None of which I was.

***

Summer 1975 or 1976: I set out from my neighborhood to head for the one where I now teach. Back then, my interests were less academic. I cared about the campus shops that catered to students; the concrete swim club with a good cheesesteak place around the corner; boys from school I might run into if I took the right turns. Did I have my teenage uniform on? The t-shirt and Army Navy Store overalls I’d embroidered and patched to within an inch of their life? Was I wearing shoes? Probably, probably, maybe not.

I ambled along, carrying a can of soda, Dr. Pepper or Frank’s Black Cherry Wishniak. My father’s car pulled up alongside. He and my mother had split up a few years prior; I saw him for weekly visits or when he drove by in his late-model Impala on the way to show a house or put up a For Sale sign. Dad’s passenger-side window sank down—he had electric. He leaned over to speak. I doubt he bothered with hello.

Should you be drinking like that on the street?

My father didn’t make us call him “sir” the way my uncles had raised my cousins to do. Nonetheless, my sisters and I had learned to answer questions without hesitation and never with slang or ambiguity. Yes or no, none of this yeah or maybe or I don’t know. We learned not to hedge responses with I think . . . because that prompted an immediate You didn’t think.

But under that broiling sun and with my guard down, I did the unthinkable. I hesitated. I couldn’t form a response because I didn’t understand his question. Sodas weren’t forbidden. It was hot out. I’d certainly bought the can with my own money. In that sliver of silence where I scrambled to make sense of his words, he dropped the matter. Another aberration.

“I’ll see ya,” he said, and drove off.

My father was born in 1926. He grew up in rural Georgia, where his own father wasn’t known as the town’s doctor or the town’s colored doctor but the town’s nigger doctor. Peonage farms and poll taxes were the order of the day, and black people landed on the chain gang for minor and manufactured infractions—claims of vagrancy, public drunkenness, loitering. In my father’s neighborhood, Colored Folks Hill, every public action had consequence and every gesture was met with judgment. My grandfather never left the house without a necktie, even to go fishing and even in the bone-melting heat of the Jasper County summers. Why wouldn’t my father flinch, four decades later, when he saw me slurping down a soda on the sidewalk, an unguarded, unmasked teenager with not a care in the world? And I, his child—hardwired to win his affection and diffuse his ready anger—why wouldn’t I absorb his admonishment, however irrelevant or confusing?

***

Most Americans know the adage, “The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.” Germans have it too—“Der Apfel fällt nicht weit vom Stamm”—though they’re specifically measuring the distance from fruit to trunk. The Spanish version has to do with splinters—“de tal palo tal astilla”—while the French rendition takes an absolutist tone: “Les chiens ne font pas des chats.”

In some way or another, most of us come to realize that we are, more or less and for better or worse, chips off the parental block. But what comes after the sidewalk-borne shock of recognition? As the years go by, these discoveries pass through a different filter—one that’s less reactive, more gentle. There’s curiosity and amusement and compassion and insight, palpable evidence that relationships continue to evolve as we make our way through life, even if one party (in my case, my father) is dead and gone. We begin to welcome these reflections and refractions, however they come. Unanticipated reckonings result, thanks to the discernment we’ve gained along the way, tempered as it is by firsthand exposure to birth and death, to faith and betrayal, to endurance and impermanence.

***

As a younger adult, any parental trait I came across was to be dissected and then excised. Forty years and a good amount of individuation later, when I tossed that drink into the trash and realized my late father’s social calculations had saturated my psyche, instead of being disturbed by the epiphany, I felt only comfort and curiosity. What other dictums and beliefs had been grafted onto me through example or instruction? And to what end? With the perspective of age, I saw that one behavior, irrelevant as it was to my lived experience, forming a bridge between me and this person I had loved, despite his thick and brittle shell. In acting out my late father’s practice, I felt his proximity. Other connections bloomed. What if, I wondered, and not without some astonishment, my stern and unyielding father allowed his street-side question to go unanswered because, in that confused silence, he grasped its irrelevance? Had my father actually backed down? I could recall no similar experience throughout my childhood, but one was enough to invert gravity.

Welcoming the likeness, the echo, isn’t the same as according it value. My father delivered me into a world so different from his that such public cautions were unnecessary. I was acting out a race play that was asynchronous, out of step with my time. Still, it raised questions about the disjunction between behavior and cultural context. What did this absorbed lesson contribute to the world, to me? If it wasn’t needed for safety, maybe it offered a cautionary tale, a reminder of how insidious racism can be, a lesson that I would need less for my survival than for my humanity.

Excerpted from "Apple, Tree: Writers on Their Parents," edited and with an introduction by Lise Funderburg (available now from University of Nebraska Press). Order here; author appearances here.