Book Excerpt: 'Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze'

Practically since its advent, fashion and art photography has been dominated by the male gaze - with women presented, and often objectified, by male photographers, and seen only as vessels for their pleasure and desire. But in recent years, a new generation of female photographers are changing that, using their photography (in galleries, in books, and on social media) to transform how women are seen, literally and figuratively.

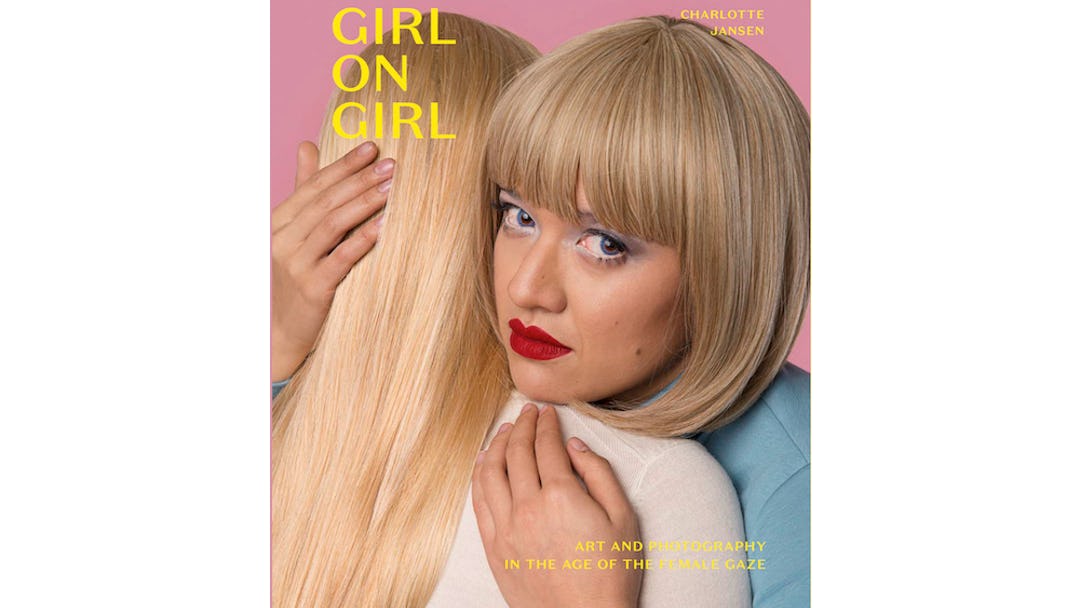

In the new book Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze (out now from Laurence King Publishing), author Charlotte Jansen spotlights the work of forty artists, all of whose principal subject matter is either themselves or other women, along with interviews and commentary on their work and this important shift in the medium. We're pleased to present this excerpt from her introduction.

FROM THE INTRODUCTION: "LEARNING TO LOOK AT WOMEN"

On my computer screen is a half-naked young woman. The flawless, golden brown skin of her back is decorated with a cornucopia of tiny, sparkly stickers of rainbows, stars, kisses, dolphins, butterflies. Simple cotton underwear – powder pink to match the bed sheets she lies on – clasps to the cheeks of her bottom. Across the knickers a single word is printed in pink: ‘Feminist’.

This photograph (by Mayan Toledano) made me angry. It would pop up again and again in my field of vision and everywhere from The New York Times to Tumblr. If you’ve used the internet in the last two years, the chances are it will be familiar to you too, and perhaps you had the same gut reaction to it as me. At the same time, it was making a huge impact. It seemed to capture the cultural predicament of the age of the female gaze: how should we look at women?

There is a fundamental pleasure in looking at women that is undeniable and unavoidable and tends to complicate the central place women have in visual culture. In the past, photographs of women were made by men for a capitalist economy to favour the male gaze and feed female competitiveness. Female visibility is therefore a fallacy: we see photographs of women every day, but we are used to looking at them in a few specific contexts: on products and billboards, in shop windows and magazine covers, in erotica and pornography. They appear similarly online, in the thick and fast slew of the trillion photographs we collectively produce and share every year. Yet photographs of women are far more provocative and complicated than these viewing circumstances prescribe.

Over the last five years, however, a growing number of the photographs of women we look at on a daily basis are being produced by women. The fact that women are taking more photographs of women – both themselves and others – than ever before is something that deserves attention. Does it matter whether Toledano’s image was shot by a man or a woman? I believe it does. When I started this book, two years ago, I was motivated not by the idea of ‘female photography’ (there is no such thing) but by the way in which the mainstream media was describing this unprecedented phenomenon of female photographers who photograph women. The dominant rhetoric gives us a narrow idea of why and how women photograph women – and what they have to offer.

The very particular place of the photograph of a woman in contemporary culture means we scarcely pause to take a second or prolonged look, but swipe swiftly on. This unequal treatment of photographs of women unfortunately connects to a wider gender inequality that affects every single country in the world. If we aren’t able to see more than an expression of feminism or femininity in a photograph of a female figure, how can we expect to see more than this when we encounter women elsewhere?

My project is pro-women, but that of the artists featured in this book isn’t necessarily. I wanted to embrace all kinds of photographs of women by women to bring them together – not to show how they are similar but to present how photographs of women are not always about feminism and femininity (although some, of course, are). We are so used to seeing images now in juxtaposition, that all photographs of women – static and silent – even when they’re made for different purposes and audiences, are forced into a dialogue with one another. A selfie by Kim Kardashian proliferates so widely that we understand any photographic self-portrait through her lens. We see photographs women take – even of other women – as narcissistic, shallow, easy. This confluence of meanings doesn’t benefit photographers or viewers. We often miss the nuances that reflect, in varying degrees, the photographer’s perspective of living in our times – that doesn’t only concern women.

Why is there a need to highlight only female photographers, if the aim is to come to photographs of women neutrally, without drawing attention to the gender of their maker? Given the long-established bias of the hetero-patriarchy, we still have centuries to go before the balance is redressed. At times, there seems to be little difference between how women photograph women and how men photograph women, but women have the right to self-objectify and to exploit without critique, just as men have been allowed to do since the earliest forms of art emerged. I came to see the feminist knickers as the beginning of an imperfect but very important process of emancipation.

Photographs taken by women do not only exist as a counterpoint to the male narrative. A photograph is an impulse – and challenge – to enquire, not a representation of truth. More often than not, I find that the photographs of women by women I see point me back to my own prejudice and misconceptions. Thanks to the generosity of the photographers on these pages, I had the chance to question my viewing habits and dig below the spectacle of surface.

In the hours I spent interviewing the 40 artists from 17 countries, I was often surprised by the reasons for which women photograph women. They can be a way to understand identity, femininity, sexuality, beauty and bodies. At times, using the female body is only a means to an end: it’s a material that is available, over which the photographer-model has total ownership and final sovereignty. The photographs women take of women can be a tool for challenging perceptions in the media, human rights, history, politics, aesthetics, technology, economy and ecology; to get at the unseen structures in our world and contribute to a broader understanding of society. What you can get is not always what you might see.

Girl on Girl – as the title suggests – is ultimately a mediation on the agency women are taking over the images that are made of them. It’s an investigation into the use and meaning of female photography now, bringing to light the plurality of situations in which a photograph is created and seen. The more we’re exposed to different types of photographs of women – more women than we will ever meet in real life – the more we can learn. ‘No genuine social revolution can be accomplished by the male’, wrote the most radical feminist writer, Valerie Solanas. It would be naive to think that photographs of women can change the world, but we can learn a lot by looking.

Excerpted from "Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze" by Charlotte Jansen. Copyright © 2019 by Charlotte Jansen. Excerpted by permission of Laurence King Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.