Former Washington Capital Stephen Peat and former New York Ranger Dale Purinton decided at an early age that they would do anything to play hockey at the highest level - to prove that they were worth it, not only as hockey players, but as people. And once it became clear that their skating and shooting and passing might not be quite enough, they hung onto those NHL dreams with their fists. They fought recklessly and relentlessly, earning big money and playing in front of stadiums full of rabid fans.

But those dreams were finite and came with devastating consequences. Purinton and Peat became addicted to drugs, were estranged from their families and have been in and out of prison. Both men live with symptoms common with the degenerative brain disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

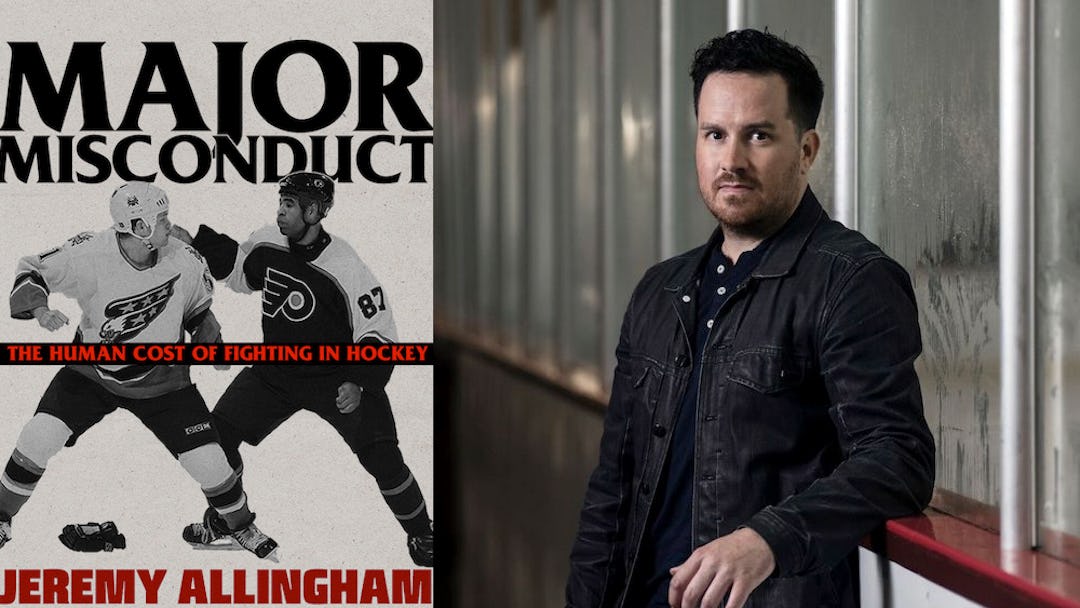

While fighting in hockey isn’t as common as it once was, it is still part of the game. But if we love hockey, and by extension, the players who excel at the sport, why do we allow them to suffer these devastating injuries? Why do we allow them to suffer after their playing days are over? Jeremy Allingham’s Major Misconduct: The Human Cost of Fighting in Hockey (out now from Arsenal Pulp Press) is a book about a dangerous sports cultural phenomenon that hides in plain sight, and leaves devastation in its wake.

FROM "MAJOR MISCONDUCT":

When you think back to the strangest way you ever met one of your friends, I’m guessing your opening line probably wasn’t “Wanna go?” To regular folk, it might seem crazy that a bare-knuckle boxing match in front of 20,000 fans would be a fertile breeding ground for a lasting friendship. But for Dale Purinton and Stephen Peat, that’s exactly what happened.

As with so many hockey players who earn their living on the fighting fringes, Dale and Stephen first met on the verge of combat. Peat was a tough, cocky sixteen-year-old taking the WHL by force for the Red Deer Rebels. Purinton was the proverbial heavyweight champion of the league with the Lethbridge Hurricanes.

“Peaty came into the Western League beating the shit out of everyone,” Purinton remembered. “And he beat up all the twenty-year-olds, tough fuckers too, that I knew. So we played Peaty one night and Peaty’s asking me to go and I said, ‘Well, when you earn it, I’ll fight ya,” but the truth is ... I didn’t want to take a chance to lose.”

So in the beginning, Peat was the young upstart trying to knock the king, Purinton, from his tough-guy throne. You can almost hear the immortal words from the end of Casablanca: “I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.” Am I right?

“Rocky Thompson and Wade Belak and all those guys were gone [from the WHL]. They all turned pro the year before me, so I was killing everyone and I had no one to fight really,” Purinton added. “And I couldn’t take the chance of losing against Peaty because he was a sixteen-year-old. And I wasn’t sure [if I would win] ’cause he was killing it.”

But despite Purinton’s success keeping the gloves from hitting the ice during that first meeting in junior in 1996, he and Peat would cross paths again in the pros. In fact, their first scrap broke out less than four minutes into Stephen’s second NHL game, directly in front of the New York Rangers’ bench at Madison Square Garden. And their violent relationship would only blossom from there.

“I ended up fighting Peaty a couple of times,” Purinton said. “And he was a super tough guy ... like, dangerous.”

The enforcers exchanged nasty words, plenty of wrestling, and a couple of haymakers, but little did they know that they were also seeding a meaningful relationship that would later bloom at a time when both men would be facing daunting challenges in their personal lives.

The thing that’s hard for the rest of us to understand is that hockey fighting is a brotherhood. The job is so singular, so punishing, and so far beyond the realm of regular work that it makes sense that these guys share a common gravitational force. They understand each other. They just get it. Purinton told me that he followed all of his fighting foes in the NHL closely, Stephen Peat included.

“There’s so much to it, man,” Dale said. “Once you’re in the league for a bit, you know each other and you pull for [them]. If a young guy’s doing well, we’d talk and it’s kind of like you stick together. You get older and guys have mortgages and families, and you want them to keep their jobs. So there’s so much more to it than just ‘Oh, two guys are goin’ out to fight.’ You become united almost when you’re in the league for a while.”

The biggest bond of all, the one that transcends even the exchange of expertly thrown punches, is the shared knowledge of how hard they train, how hard they punch, and how hard it hurts. “You respect each other,” Purinton told me. “You watch each other ... no one plays like us. It’s the hardest job in that league.”

And it’s that indelible connection between fighters that made the tragic deaths of Wade Belak, Rick Rypien, and Derek Boogaard back in 2011 so difficult for fighters to absorb. Enforcers across the continent saw themselves in those men who died. Integrating the deaths into their lives and, by extension, gaining a deeper understanding of their own mortality, for many, was a tough pill to swallow. Dale Purinton counts himself among those who were devastated by the news. “They’re like your brothers, right?” he said. “They’re basically the same as you. They live the same lifestyle, they grew up the same, they have the same job. You just relate so much to them.”

Purinton has proudly represented that brotherhood of the fighter and showed his friendship for Stephen Peat by reaching out to him when he landed in rehab on Vancouver Island. He wanted to see Peat bounce back from the brain injuries, the drugs, the homelessness, and the jail time. “It’s heartbreaking knowing he’s struggling,” Purinton said. “I would do anything for him. It’s terrible.”

Dale wants the same for all of his fellow former enforcers. That’s why he lobbied high-profile American politicians in Washington, DC, to take a closer look at concussions in pro hockey. That’s why he was one of the leaders of a class-action lawsuit against the NHL.

But it turns out Dale, like so many fighters, has a harrowing story of his own. His journey has taken him through the depths of drug and alcohol abuse, estrangement from his family, and the prospect of hard time in a maximum security American prison.

***

Picture a twenty-three-year-old Canadian hockey player hitting the ice at Madison Square Garden. He feels the cold wind on his face and the smooth ice under his skates. The spotlights track across the dark ice surface as 20,000 fans welcome him with a thunderous roar.

This is midtown Manhattan, New York City. The center of the universe for sports, arts, and entertainment. And within New York City, MSG is the epicenter of the biggest, most important entertainment there is on the planet. The lights don’t get any brighter. The fans don’t get any crazier. The media doesn’t get any fiercer. When the phrase “hitting the big time” was coined, this has to be what the originator had in mind.

But wait just a second. Let’s hit that rewind button. Go back, back, back, nineteen years to 1981, and that same kid, four years old, is riding his bike in the middle of a quiet rural street in sleepy Sicamous in central British Columbia.

Now, you may not think bike riding is all that noteworthy for a four-year-old. Almost every kid does it. But that bike was the only one the Purinton family owned. It was the only bike for TEN kids. Dale Purinton was the youngest of his six brothers and three sisters.

“I’d be riding that bike, and I’d be the first one right on that bike,” Dale reminisced. “And I’d be with some of my friends and I’d see my brother walking with his buddies and being like, ‘Hey guys!’ and being nice to us, and all they were doing was sucking me into knocking me off my bike. So this was like an ongoing thing with food and everything. You were just tough or not, right? You are tough or you put up with it.”

Starting at the ripe young age of four, Dale was fighting for his bike, for his food, and for his place in the world. And it only progressed from there. Dale fought in school, he fought on the street, he fought in the bar, and eventually, he fought all the way to the National Hockey League.

This is the unlikely story of how Dale Purinton went from being knocked off his bike on a tiny hobby farm in a BC resort town, to Madison Square Garden, to the depths of drug and alcohol abuse, and all the way to a New York State maximum security prison and back again.

Excerpt from "Major Misconduct," © 2019 by Jeremy Allingham. Available now from Arsenal Pulp Press.