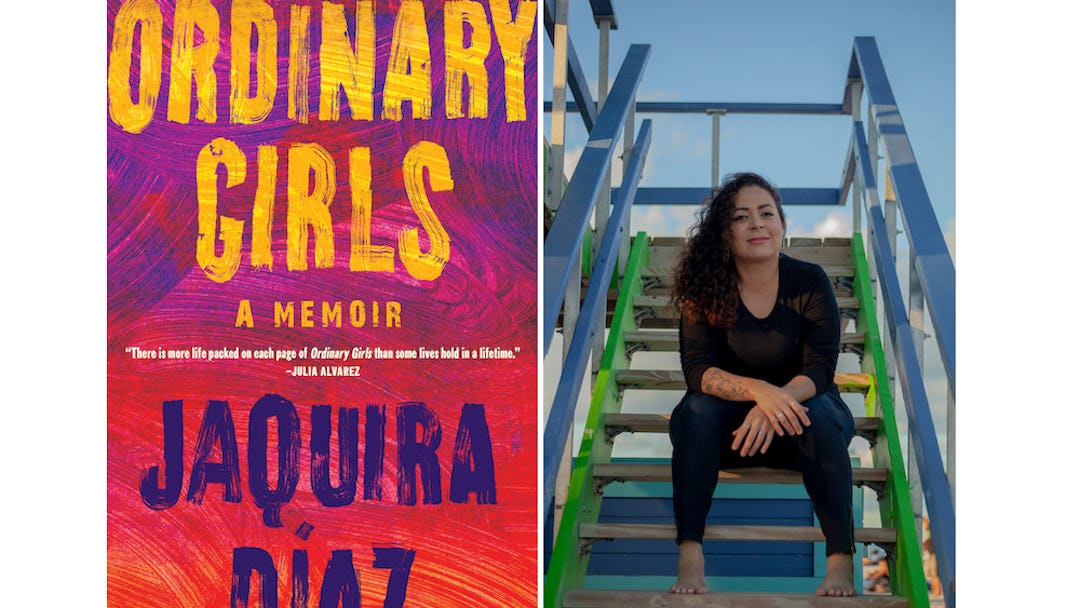

In her scorching new memoir Ordinary Girls (out now from Algonquin Books), author Jaquira Diaz takes on the coming-of-age story from her unique, queer Puerto Rican perspective - tackling racial and sexual identity, domestic abuse, poverty, mental health, drug abuse, suicide, and much more.

We're pleased to present an excerpt from this important work.

FROM "ORDINARY GIRLS"

The first time she saw my father, my mother knew he was hers. She was in high school. He was in college. She lied about her age. She had always looked older, my mother, and by the time she was fourteen, Grandma Mercy was already leaving her to care for two of her sisters, twelve-year-old Xiomara and one-year-old Tanisha, while she was at work.

My father says he didn’t know my mother’s real age, that she’d told him she was eighteen, that he found out only when Mercy caught them in bed. My mother says he didn’t really find out until they were applying for their marriage license a week later, when he finally got a look at her birth date.

My father had been a college activist, protesting the naval occupation of Culebra, studying literature,writing poems about American colonialism in Puerto Rico. My mother—so young, so desperate to leave her abusive mother, so in love with my father— would’ve done anything to keep him.

Sometimes when I write this story, I think of my mother as the villain, tricking my father, knowing the exact time my grandma Mercy would come home from work, leaving the bedroom door unlocked, forcing him to become a husband, a father, when what he really wanted was to read books and write poems and save the world. How maybe I wouldn’t be here if Grandma Mercy hadn’t threatened to have him thrown in jail.

Sometimes it’s my father who is the villain. The brilliant college student who pretended not to know my mother’s age as he slithered his way into her bed. How he decided to ignore the school uniform folded neatly and left on a chair in the corner of her bedroom.

They are different people now, divorced more than twenty-five years. But no matter how much they’ve changed, there is always this: My mother loved my father obsessively, violently, even years after their divorce. My father was a womanizer, withdrawn, absent. And it was after three children, after leaving Puerto Rico for Miami, after eleven years of marriage, after my father left her for the last time, that my mother started hearing voices, that she started snorting coke and smoking crack. But each time I write and rewrite this story, it’s not just my mother’s intense, all-consuming love for my father that destroys her. It’s also her own mother, Grandma Mercy. And her children—my older brother, my little sister, and me. Especially me.

By the time my mother was twenty-two, she had three children. She’d already been a mother for a third of her life. It was 1985. These were the days of Menudo and “We Are the World,” the year Macho Camacho gave a press conference in a leopard-skin loincloth as Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” blared from radios across theUnited States. In one month, the space shuttle Challenger would explode while all of America watched on television, entire classrooms full of kids, everyone eager to witness the first teacher ever launched into space.

In those days, Mami teased her blond hair like Madonna, traced her green eyes with blue eyeliner,applied several coats of black mascara, apple-red lipstick, and matching nail polish. She wore skin-tight jeans and always, no matter where she was going, high heels. She dusted her chest with talcum powder after a bath, lotioned her arms and legs, perfumed her body, her hair. My mother loved lotions, perfume, makeup, clothes, shoes. But really, the truth was my mother loved and enjoyed her body. She walked around our apartment butt-ass naked. I was more used to seeing her naked body than my own. You should love your body, my mother would say. A woman’s body was beautiful, no matter how big, how small, how old, how pregnant. This my mother firmly believed, and she would tell me over and over. As we got older, she would teach me and Alaina about masturbation, giving us detailed instructions about how to achieve orgasm. This, she said, was perfectly normal. Nothing to be ashamed of.

While my father only listened to salsa on vinyl, Héctor Lavoe and Willie Colón and Ismael Rivera, my mother was all about Madonna. My mother was Puerto Rican but also American, she liked to remind us, born in New York, and she loved everything American. She belted the lyrics to “Holiday” while shaving her legs in the shower, while making us egg salad sandwiches served with potato chips for lunch. She talked about moving us to Miami Beach, where Grandma Mercy and most of our titis lived, about making sure we learned English.

On New Year’s Eve, she made me wear a red-and-white striped dress and white patent leather shoes. Itwas hideous. I looked like a peppermint candy. She styled my hair in fat candy curls and said she wanted me to look like Shirley Temple. I had no idea who Shirley Temple was, but I hoped she didn’t expect me to be friends with her. I wasn’t trying to be friends with girls in dresses and uncomfortable shoes.

I knew that these were things meant for girls, and that I was supposed to like them. But I had no interest inmy mother’s curtains, or her tubes of red lipstick, or her dresses, or the dolls Grandma Mercy and Titi Xiomara sent from Miami. I didn’t want to be Barbie for Halloween, like my mother suggested. I wanted to be a ninja, with throwing stars and nunchucks and a sword. I wanted to kick the shit out of ten thousand men like Bruce Lee. I wanted to climb trees and catch frogs and play with Star Wars action figures, to fight withlightsabers and build model spaceships. I didn’t have a crush on Atreyu from The NeverEnding Story, like my brother said, teasing me. I wanted to be Atreyu, to ride Falkor the luckdragon. When I watched Conan theDestroyer, I wanted to be fierce and powerful Grace Jones. Zula, the woman warrior. I wanted her to be the one who saved the princess, to be the one the princess fell for in the end.

(Years later, would I think of Zula during that first kiss, that first throbbing between my legs? It would be with an older girl, the daughter of my parents’ friends. We’d steal my mother’s cigarettes, take them out back behind our building, and light them up. She would blow her smoke past my face, stick her tongue in my mouth, slide her hand inside my shorts. How she’d know just what to do without me having to tell her—this was everything, this butch girl, so unafraid, getting everything she wanted. And how willing I was to give it to her.)

Our new neighbor arrived in the middle of the night, carried her boxes from somebody’s pickup into herliving room, then waved goodbye as it drove away. She arrived in silence, filling the empty space of theapartment next door, where nobody had ever lived as long as I could remember, hung her flowerpots from hooks on the balcony. She arrived with almost nothing, just those plants and some furniture and her daughter Jesenia, a year older than me. The morning after, Eggy and I were outside catching lizards, holding onto them until they got away, leaving their broken-off tails still wriggling between our fingers. She stepped out on her balcony, watering her plants with a plastic cup. “Guess you have a new neighbor,” Eggysaid.

La vecina, as we learned to call her, was nothing like Mami. She wore no makeup, a faded floral housedress and out-of-style leather chancletas like my abuela’s, her curly brown hair in a low ponytail. She had deep wrinkles around the corners of her eyes, although she didn’t look as old as Abuela. When she looked up at Eggy and me, she smiled.

“Hola,” she said. “Where’s your mom?”

“Working,” I said.

She pressed her hand to her cheek. “And she lets you play outside by yourself?”

“Sure,” I said.

We talked for a while, la vecina asking us questions about the neighborhood, about the basketball courts, about what time the grano man came by on Sunday mornings. Eggy and I answered question after question, feeling like hostages until my father emerged.

“Buenas,” Papi said.

La vecina introduced herself, and Papi walked over, shook her hand over her balcony’s railing. They got to talking, ignoring me and Eggy, Papi smiling, the way he never smiled. My father always had a serious look on his face, a look that made him seem angry, even when he was happy. And he was always trying to look good, ironing his polo shirts, grooming his mustache every morning, massaging Lustrasilk Right On Curl into his hair before picking it out, even if he was just lying around the house on the weekend. The only time my father dressed down—in shorts, tank tops, and his white Nike Air Force high-tops—was when he played ball or when we went to the beach.

La vecina laughed at something he said, and my father patted his Afro lightly. When I saw the opening, I tapped Eggy on the shoulder and we took off running toward the basketball courts.

Excerpted from "Ordinary Girls" by Jaquira Diaz (out now from Algonquin Books). Used by permission.